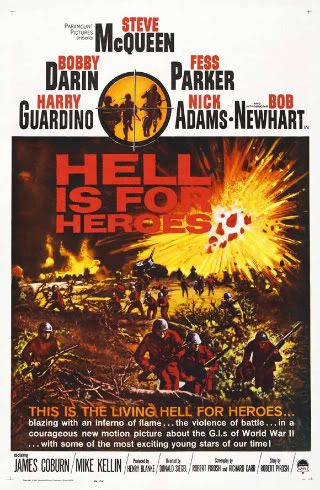

Don Siegel’s Hell is for Heroes (1962) is one of those small scale, low budget war movies that bears comparison with some of the stuff Sam Fuller knocked out at the beginning of his career. It’s the kind of film that keeps the focus firmly on the guys at the bottom of the ladder, and thus manages to address the futility and brutality of war while still acknowledging the courage of the lowly, ordinary grunts who find themselves having to be extraordinary just to stay alive. War movies in the 1960s would increasingly move towards the big budget spectacular, but this one is almost a throwback to the previous decade due to the small cast and character driven plot.

The story here concerns a battle weary squad of US soldiers on the fringes of the Siegfried Line in 1944. Although their fighting strength has been severely weakened the troops aren’t overly anxious as they figure they’re on the point of being shipped out and finally heading back home. Their meagre ranks are added to with the arrival of a replacement, Reese (Steve McQueen). He’s a former master sergeant, busted back to private for flaking out and stealing a jeep. In fact, Reese is a man dangerously near the end of his tether; his distinguished service record has saved him from falling further but he keeps on chipping away at the corners of army discipline. An evening’s visit to the nearby town’s off limits bar would probably have done for him if it hadn’t been for the intervention of Sergeant Pike (Fess Parker), an old acquaintance. When news comes through that there will be no welcome departure, just a move back onto the line, the only man not to show dismay is Reese. For these men the news is about to get even worse, as they are to be left behind as a temporary rearguard while the bulk of the force move on. The challenge is for the isolated squad to fool the Germans into thinking that they’re a much bigger force. To this end the troops devise a number of ingenious ploys, from running a backfiring jeep in low gear to simulate the sound of a tank to stringing ammo boxes full of rocks through the bushes so the enemy might take their rattling for the movements of patrols. This is all well and good but a brutal assault by a German patrol (which sees Reese in his element, even savagely hacking one man to pieces with a butcher knife) renews the danger. With no guarantee when the main force will return to back them up, the squad need to decide between sitting it out in hope or taking the initiative and trying to knock out a pillbox. Reese urges action while the cautious Sergeant Larkin (Harry Guardino) counsels patience. In the end, a stray shell makes their decision for them and Reese gets to lead a tense sortie through a minefield. There are no happy endings in this movie, just sudden and graphic deaths, hard decisions, and harder consequences. Even the final scene offers no real respite; the army surges on amid fallen bodies and there’s no end in sight – more positions will have to be taken and more men will have to give their lives.

The part of Reese was ideal for Steve McQueen who must have relished playing the moody loner unburdened by excess dialogue, and it had the added bonus of handing him the opportunity to show off all those twitchy mannerisms that audiences have come to associate with him. It’s really McQueen’s picture from beginning to end and it’s always a pleasure to watch him keep all that angst and bottled up machismo raging just below the surface. He gets some good support from Fess Parker and Harry Guardino, as the respectively sympathetic and exasperated sergeants, and from a bespectacled James Coburn – the squad’s technical jack-of-all-trades. The novelty casting of Bob Newhart and Bobby Darin is altogether less satisfying, but it’s not enough to do any serious damage to the film. Don Siegel’s direction is as tight and professional as could be, and he works wonders on what must have been a small budget. The stark monochrome photography adds just the right touch of bleakness and, while this is essentially a character study, Siegel’s handling of the action scenes is urgent, exciting and realistic.

Paramount’s R2 DVD of Hell is for Heroes offers an excellent transfer. The movie is presented 1.78:1 anamorphic and looks in very good shape all the way through. There’s not an extra to be found on the disc, which is the only black mark against it for me. This isn’t one of the best known war movies, nor is it likely to be one of the more familiar works of either McQueen or Siegel. However, for fans of the genre, star or director it does deserve to be seen. It’s a powerful little movie that doesn’t try to manipulate the viewer or preach – it simply presents a dispassionate view of war and the men involved.