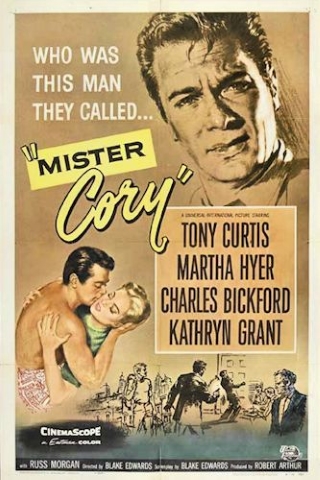

Another day, another movie that appears to defy categorization. Of course, there is no good reason why anyone ought to feel it is necessary to categorize a movie, but it is a pastime that we film fans like to indulge in. Mister Cory (1957) does not comfortably wear any of the labels I’ve seen hung on it, not that there are many people who have actually commented on the film one way or another. It has been referred to variously as a crime picture, a drama, even as a film noir. I guess there are elements of all those genres and styles to be found there, but none of them are entirely satisfactory. Perhaps one could call it a Blake Edwards film. However, I’m not sure I would be able to define that either, certainly not for something coming at this early stage of his career as a director/writer. So what is it? There is a hint of The Great Gatsby about the setup, it maybe even casts a glance in the direction of Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (and Stevens’ adaptation A Place in the Sun), and there is too a touch of the humor that Edwards brought to so many of his films. If anyone can produce a convenient label out all that, I salute them. Frankly, I’m happy enough to just think of it as a good movie that is not as well known as it might be.

The first view of Cory (Tony Curtis) is of a young man making his way along a heaving sidewalk in Chicago, one of those tenement slums where all human life is to be found, the kind of place where hope can all too often wither or where the seeds of all-consuming ambition can take hold. Cory is a man with ambitions, and the first steps towards realizing them are going to see him keep right on walking out of the neighborhood he grew up in. They carry him out of the city to one of those exclusive lakeside resorts where only those with blue blood, deep pockets and an Ivy League education can afford to lunch and lounge with poise. Now Cory may not have any of the usual qualifications to hang out in such environs, but he does have poise, even if his is borne of audacity. He’s hired as a busboy, right down at the bottom of the pecking order. However, he has no intention of remaining in that lowly position and employs a combination of cunning and chutzpah to hobnob with the cream of society and keep an eye on the main chance. To be precise, he has set his sights on Abby Vollard (Martha Hyer), an ice cool society blonde, and for a time it looks as though he might just pull off the deception and bag the prize he so craves.

However, that would be too simple and dramatically, not to mention ethically, unsatisfying. No, a tale requires a twist if it’s not to become too predictable. So, with his imposture revealed and his scheme shattered, Cory is forced to move on. He does so, and moves far and wide, returning to his roots in a way as he falls back on the skills as a gambler he acquired early in life. All of which segues into the second part of the story, the rise of Cory as a slick and smooth front for Ruby Matrobe (Russ Morgan), a big man in the Chicago underworld. With money no longer an object, prestige and deference (even from those who once demanded the same of him) his constant companions, he would appear to have fulfilled his ambitions. Yet there is still the ever present itch that he yearns to scratch – Abby. That he is now in a position to woo her successfully is complicated by both the need to conduct the business and romantic equivalent of a high wire act. Her long time fiancé (William Reynolds) is the son of a man with significant political clout, capable of delivering a knockout blow to Cory’s backers and by extension to Cory himself. And then there is the sneaking suspicion he begins to have that maybe Abby’s now grown up sister Jen (Kathryn Grant) is the one he should have been pursuing.

Mister Cory was adapted from a Leo Rosten novella, which Tony Curtis bought the rights to and had Blake Edwards adapt for the screen. It has a classic “rise and fall” structure that makes for good drama. There is a lot of emphasis placed on the nature of ambition, the old exhortation to be careful what one wishes for never being far from the surface, as well as other maxims regarding all that glitters and so on. This is all very well, but not that compelling at the same time. On the other hand, the movie is on much firmer ground when it posits the theory that human nature is immutable, rendering notions of grasping ambition, social climbing, and all the deceit and falseness that tend to accompany those wraiths redundant. At the heart of the story is the belief that running away from one’s true self, denial of one’s nature in essence, is a doomed enterprise. Sooner or later, this dawns on pretty much every character. It can be seen in Charles Bickford’s veteran gambler, a man who intuitively knows when the game has grown stale. Cory may be one of the last to fully grasp this, though it does grow on him gradually; there is a terrific scene where, with success won, he wanders back to the old neighborhood where he grew up, strolling down the middle of the empty nighttime street, gazing at the building he was born in, the locations that spelt loss and tragedy and the places he learnt his trade. Lost in the cool solitude of reminiscence, surrounded by the echoes of voices long gone and words drifting across time, his past and present knit together in a moment that marks the beginning of his acceptance of self.

Curtis deftly captures the many facets of the character, the roguish charm that never really deserts him, the drive concealed behind this, and the awareness that all the polish and front is simply that, a veneer that does nothing to shrink the distance between the one-time street urchin and the elegantly clad dream merchant he has cast himself as. Again, I’m drawn back to that scene I mentioned above, so much of the character is encapsulated in it after all, with Russell Metty’s camera tracking the lone figure via a crane shot that shifts from cool objectivity to intimacy and serves to highlight the contrast between the slick facade Cory has adopted and the grimy background that produced him. With the lens focused on his troubled features, it’s clear to see that he hasn’t traveled so very far. Martha Hyer was an actress who flirted with true stardom yet never quite broke through. Around this time she had roles in some good movies – Battle Hymn for Douglas Sirk, and she earned an Oscar nomination for her work in Minnelli’s Some Came Running. The part of Abby called for someone who was able to convey chilly snobbery in tandem with a weakness for slumming and hypocrisy, which Hyer gets across successfully.

Kathryn Grant graced some fine films throughout the 1950s and she brings a liveliness that is quite infectious to the part of the younger Vollard sister. Playing the third arm of a romantic triangle frequently proves to be something of an unrewarding task, but William Reynolds takes it on manfully and achieves a degree of pathos as the flawed fiancé. The reliably crusty Charles Bickford brings dry humor coupled with down to earth wisdom to the table and acts as a stabilizing influence on his often hot-tempered protégé. Another interesting piece of casting is band leader Russ Morgan as the Chicago hood, something which sounds like an odd choice but which ends up working out just fine. Finally, a word for Henry Daniell, a man whose long career saw him regularly playing highly cultured villains. He brings great suavity to his work here, insisting on good manners and propriety at all times, the very personification of moral rectitude. And then he gets to deliver a genuinely killer punchline to wrap up the climactic confrontation in the casino.

Mister Cory has had DVD releases in France, Spain and Italy, and I strongly suspect all of them will be using the same source. I have the Italian release, which presents the movie in the correct ‘Scope ratio. It’s a colorful if rather soft transfer though and the images I’ve added above should give some idea of how it looks. I would love to see this film get a brush up because it really deserves better treatment. I hadn’t seen it before and I’ve never heard anything much about it either. Every year brings a few new discoveries for me and I feel this movie rates as the most enjoyable and worthwhile of them so far in 2023.

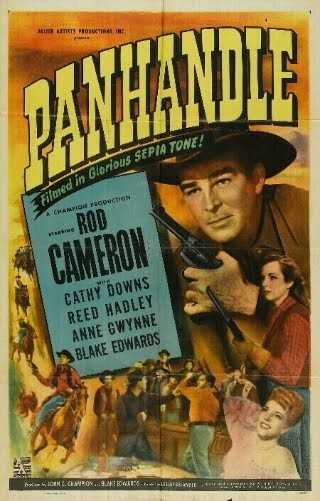

Certain plot devices come up time and again in westerns, so much so that they can start to feel like old friends after a while. On occasion we even get a whole cluster of them all intermingled in one movie, although one tends to dominate when such a situation arises. Panhandle (1948) blends together the tale of the town tamer, the outlaw forced back into his old ways, and the perennial matter of settling scores. It’s that latter element – the quest for revenge, or perhaps it would be more accurate to talk of justice here – that comes to the fore in another stylish example of Lesley Selander’s work.

Certain plot devices come up time and again in westerns, so much so that they can start to feel like old friends after a while. On occasion we even get a whole cluster of them all intermingled in one movie, although one tends to dominate when such a situation arises. Panhandle (1948) blends together the tale of the town tamer, the outlaw forced back into his old ways, and the perennial matter of settling scores. It’s that latter element – the quest for revenge, or perhaps it would be more accurate to talk of justice here – that comes to the fore in another stylish example of Lesley Selander’s work.