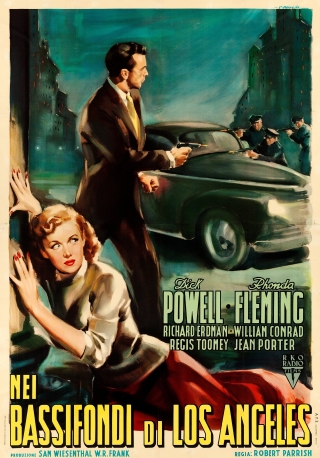

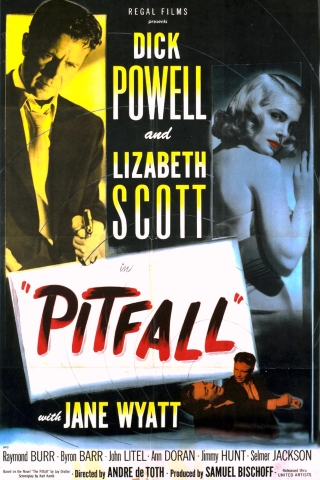

Initially, I had planned to post something different today, but that can wait. Sometimes circumstances just produce odd little coincidences, we end up viewing a movie or reading a book or story that quite by chance seems to hold a mirror up to events unfolding before us. The very fact this occurs without our actively having sought out some visual corollary makes the effect all the more striking. It is sobering to remember too that 76 years ago people were warning of the dangers of complacency, ringing alarms over the way corruption and graft can creep surreptitiously into the fabric of life, how bullies and self-serving chiselers can threaten and intimidate while hiding behind the cloak of laws they manipulate and soil rather than respect. Even more unsettling is the fact The Sellout (1952) painted its picture of contemptuous authoritarianism as a localized, contained phenomenon. It should give us all pause when we realize that virtually the same unsavory themes are now being played out in real life both nationally and internationally.

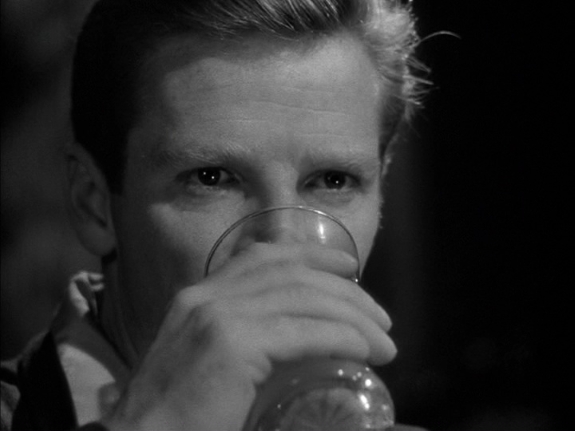

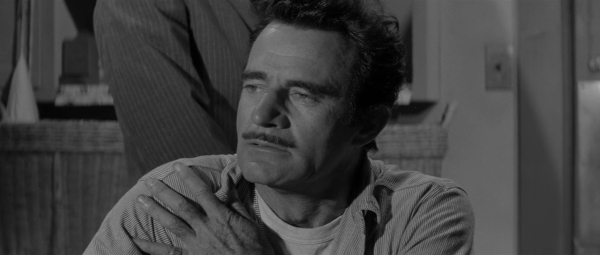

Structurally, The Sellout feels like a film of two distinct halves for the simple reason that the action plays out through the eyes of two quite different protagonists – newspaper editor Haven Allridge (Walter Pidgeon) and ambitious state attorney Chick Johnson (John Hodiak). It opens with Allridge, with the stoicism, stability and straight-down-the-line respectability an actor like Pidgeon effortlessly projects. That a man such as this – successful, comfortable and with a solid family life – should end up being rolled by a sly grifter (Thomas Gomez), tossed behind bars in a cell full of lowlifes and humiliated is supposed to shock, and it does so. That he is forced (in a scene that is as suggestively unpleasant as the production code of the time would allow) to witness the degradation of his companion, a man he generously offered a ride home, hammers this point home even more resoundingly. His sense of outrage is palpable and, using the tools available to him through his profession, he embarks on a campaign to expose the rottenness which has been growing steadily in his state. And then, just as he appears poised to land the killer blow, he stops, dropping out of sight for a time before inexplicably deciding to relocate and take up a new job in Detroit. The reason for this sudden reversal is eventually revealed through the diligent and relentless investigative work of Johnson, resolutely assisted by local cop Maxwell (Karl Malden).

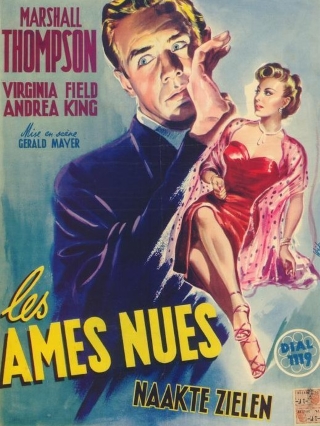

Gerald Mayer had made the tense and tightly confined Dial 1119 a few years earlier and he does sound work here, certainly good enough to leave me wishing he had racked up a few more titles in his relatively modest feature filmography before moving into his long and prolific career directing for television. Exposé movies can become dull affairs at times, sometimes due to the limited nature of whatever issue it is that’s being highlighted, or maybe the one-dimensional characters that can populate them. The Sellout avoids those pitfalls due to both the quality of the acting and the (probably unexpected) timelessness of the script. Both Pidgeon and Hodiak bring subtle shading to their characters, the former especially, and aren’t just the impossibly noble figures that one sometimes sees.

A strong supporting lineup is always a boon, adding weight and interest to those scenes where the main players are absent or otherwise sidelined. The Sellout has genuine depth in support with Karl Malden, Audrey Totter, Everett Sloane, Cameron Mitchell, Thomas Gomez and Paula Raymond all making significant contributions at various vital points in the narrative.

However, even a stellar cast working well can struggle to make an impression if the material they are handed is subpar. There is forever a risk of any issue driven picture dating badly, in the sense that the themes explored may be tied inextricably to situations which have since lost relevance. Normally, I would say it’s fortunate that concerns depicted still resonate and clamor for attention today. In the case of The Sellout, I can’t help feeling that any comment acknowledging that fact really ought to be preceded by the word ‘unfortunately’. That said, this is a fine film, one that is in the unusual position of being an even more worthwhile viewing experience today than would have been so when it was made. With that, I shall leave you, without further comment, with a transcription of the speech John Hodiak makes during the climactic courtroom scenes:

“In the mute parade of these frightened citizens. Weak men and strong men who have become weak and big men who have become little. All frightened. Their very silence testifies to that more strongly than shouted words… Their first protection was the law. Out of the domination of brutal and ruthless men, the law was turned against them. There is another protection: public opinion. Public Opinion finds its voice in the press, the free press. Here, a courageous editor brought his newspaper to the battle: he fought. His blows began to hurt. And little men who’d been fooled or frightened began to stir… to fall in behind his waving banner. But then something happened. Exactly what happened we don’t know. We may never know. But we do know that the voice of the public was stilled. The press had been enslaved… and when the press lost its freedom, these people lost their freedom. And Freedom is no idle phrase, it’s close and personal. It’s the right of Wilford Jackson, Walter Higby, Bennie Amboy. These people… of you and me… weak and strong… big and little to follow our normal pursuits in peace and without fear. Your Honor, the situation I’m covering here today is a symptom of civic cancer. We smell its malignancy not only in the terror-stricken avoidance of civic duty by this parade of bribed and intimidated witnesses, not only in the treasonable misconduct of public officials, not only in the violence, abuse, and even death we’ve observed… but in the growing helplessness of all decent people and their apparent apathy to the tightening grip of these ruthless men. This cancer must be traced down to its roots. It must be cut out or it will spread. And when it spreads far enough… the community will die. I therefore plead that this court free the people of Bridgewood County from the dictatorship of fear by finding cause to bind these defendants over for trial. The state rests.”