Popular wisdom holds that when a film is adapted from a novel the original source material is inevitably superior. I’m not sure how true that really is though. I suspect that this maxim has come to be as a result of the disappointment felt by a loyal readership when filmmakers have had to alter the material to make it work on the screen. We all naturally form a mental picture of characters and places when we read about them, but when others place their interpretation in front of us it can be an underwhelming and perplexing experience. Man Hunt (1941) is Fritz Lang’s interpretation of Geoffrey Household’s novel Rogue Male. Since I saw the movie first, many moons ago, and only later read the novel, my own preference is for the film version. In truth, I found the book to be a bit of a letdown – not that it’s actually bad or anything, but just because it lacks Lang’s little stylistic touches and the character interaction that helps the film pack a greater emotional punch.

The movie is basically a chase story which utilises that old chestnut of the hunter becoming the hunted. Alan Thorndike (Walter Pidgeon) is a big game hunter of some renown who has grown weary of the traditional prey. In Germany, on the eve of WWII, he finds himself closing in on the “most dangerous game” – man. And not just any man at that. Perched high on a hilltop, he focuses the cross-hairs of his hunting rifle on one Adolf Hitler. With a live round in the chamber, he has only to touch the trigger to forever alter the course of world history. However, for Thorndike this is merely a sporting stalk – an attempt to get close enough to the prey to make the kill itself a purely technical issue, for he has lost his taste for the taking of lives. But fate has other plans for Thorndike; such a simple and unexpected thing as a leaf falling across his telescopic sight causes him to twitch at the wrong moment and thus be discovered by a passing sentry. He is hauled away to be interrogated, tortured and presented with an ultimatum – his life in exchange for a signed confession that he was acting under orders from the British government to effect the assassination of Hitler. Realising the consequences of any such confession, Thorndike refuses and finds himself sentenced to death. Chance, and the natural world, once again comes into play when the faked accident that is supposed to claim his life doesn’t quite come off. From here on Thorndike must run for his life, first to a freighter and then to an England that is positively hiving with Nazi agents and fifth columnists all directed by the suave and sinister Quive-Smith (George Sanders).

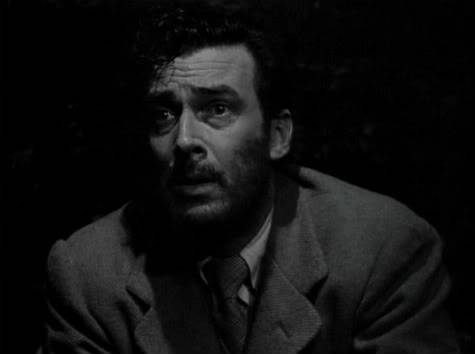

Fritz Lang brought a very noirish atmosphere to what is a fairly standard adventure thriller. The sets that represent London are bathed in deep, dark shadows that promise danger and death for the unwary. He has his hero ruthlessly driven further and further underground, his world shrinking by the minute, until he finally finds himself walled up within the very bowels of the earth. Walter Pidgeon performs well as Thorndike and effortlessly handles the character shift from a man who has achieved a degree of mastery over nature itself to one who becomes desperate, friendless and riddled with guilt. George Sanders made a career out of playing sophisticated and detached villains so the part of Quive-Smith was one he could manage with his eyes closed, but that’s not to take anything away from his performance. Joan Bennett would eventually make three films with Lang, of which Man Hunt was the first. Her role as the prostitute (never explicitly stated but clear enough all the same) who helps Thorndike and falls for him is a large part of what makes the film work, adding much needed humanity and a genuinely touching quality to a very dark tale. John Carradine also deserves a mention for his turn as the cadaverous assassin hounding Thorndike and leading to an excellently filmed confrontation within the London Underground system.

Man Hunt was long absent on DVD until Fox finally released it in R1 last month. The disc is up to the usual high standard from that company, sporting a sharp, clear image with wonderful contrast. There’s a commentary included by Patrick McGilligan along with a short featurette and advertising galleries. The only bad thing to say is that this title looks like it may well be the last classic release we’re going to see from Fox for some time, and that’s all the more galling given the high quality of their product. All told, Man Hunt is a fine film, first rate Lang, and a title that I’m just glad was able to make it out before Fox decided to shut up shop.