Crime has always acted as an effective hook to snare an audience. The reason? I guess it comes down to the challenge of being presented with a puzzle, even when it’s not an especially taxing one, that helps to draw in so many people. Even when the crime is not the principal feature of the movie it still adds a little spice, maybe broadening the overall appeal. East Side, West Side (1949) is at heart a slick melodrama, the kind that MGM was adept at making. Somewhere around the halfway mark it manages to work in a murder mystery, administering a shot in the arm to a plot which had been in danger of growing slightly listless and predictable.

The voice-over narration which introduces the movie has Jessie Bourne (Barbara Stanwyck) maintaining that the New York she inhabits is nothing special really, a place where people’s lives are mapped out in much the same way as they are in less celebrated towns. Yet the New York we are subsequently drawn into is different, it’s stylish and sophisticated and sleek, with well-to-do types very obviously doing well. Jessie Bourne is the daughter is one of the great ladies of Broadway, her husband Brandon (James Mason) is a successful financier with blue blood and all the polish and accomplishment it brings. The conversation appears as bright and dazzling as the crystal and china on her mother’s supper table, and every bit as brittle. That bright glaze that surrounds the Bournes is but a thin veneer, a superficial sheen that is riven with the kind of hairline cracks that are only visible when viewed outside of the honeyed glow of pampered privilege. You see, Brandon Bourne is an incorrigible philanderer and something of a lost soul, a man floundering in a sea of temptation, ostensibly in love with his wife yet powerless to resist the lure of forbidden fruit. The most persistent interloper in the Bournes’ garden is the relentlessly sexy Isabel Lorrison (Ava Gardner), a supreme huntress in the field of seduction. She had an affair with Brandon in the past before moving away but has now been let loose once again to prowl the streets and clubs of Manhattan. That she is stalking Brandon mercilessly is never in question, and his assertions that he’s a reformed character have a hollow ring, not least to his own ears.

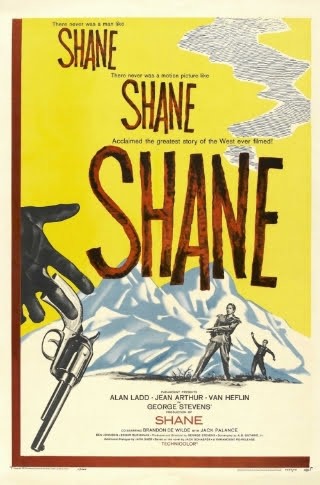

Jessie Bourne’s wronged woman is on a different path though. Frustrated by her husbands serial infidelity while simultaneously paralyzed by her love for him and her inability to envisage a life without him, she appears to have reached an impasse. By a convoluted mix of coincidence and curiosity, she encounters mannequin Rosa Senta (Cyd Charisse), who in turn brings her into contact with Mark Dwyer (Van Heflin). Dwyer is a former policeman now working in some ill-defined role as an intelligence operative in post-war Europe. His arrival on the scene has a twofold effect, affording Jessie a glimpse of how her life could be without the constant fear of abandonment by her wayward husband and then later assuming a more professional role as an impromptu investigator when murder gatecrashes this elite atmosphere.

“That’s what you don’t get at home. That’s what you’ve missed isn’t it! It’s so tiresome being restrained and soft-spoken and gentlemanly. What you really want is to be a little rotten, like me!”

Those words, spoken with passion and animation, by Ava Gardner’s character at a decisive moment go some way towards clarifying the hold she has over Brandon Bourne. It’s a superb piece of casting really, Gardner was near her peak at this stage and commands attention whenever she is on screen. It is quite impossible to take your eyes off her and it’s very easy to see how Mason’s playboy is drawn inexorably to this smouldering siren. She is earthy and forthright, candid with regard to what she wants and every bit as frank in her assessment of herself. Essentially, she is the polar opposite of Jessie’s contained refinement. Even though the main focus of the story is on Jessie’s three day trek to self-belief and her realization of her own worth as an individual, it’s not the most compelling feature. The part is well enough defined and Stanwyck’s work is up to her usual standard, but it’s a relatively straightforward one. It would be unfair, I think, to refer to it as bland but there’s a touch of inevitability to the path traced, not to mention a dearth of internal conflict.

James Mason, on the other hand, does get something meatier and more complex to sink his teeth into. This was one of his earliest Hollywood films and his suave ambiguity was well used. His character’s acknowledgment of his flaws and weaknesses invites the viewer to weigh this man up, to consider him rather than merely sit in judgement. It’s the cocktail of arrogance, insecurity and self-awareness that lends a wretched and abject aspect to the final image we have of him, a portrait of vanity bereft.

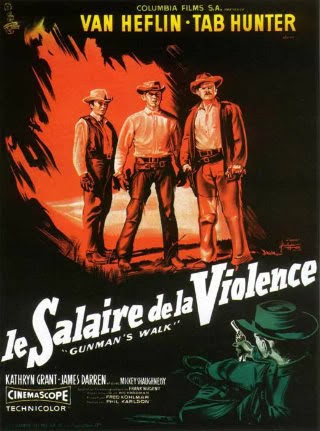

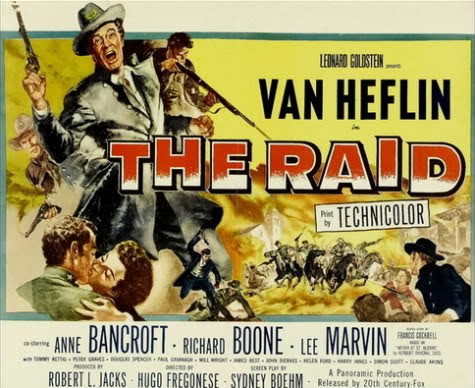

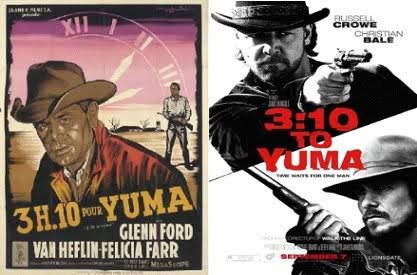

Van Heflin’s role is a little odd or contrived. It’s almost as though he is parachuted into the picture as some transient righter of wrongs, a bluff and hearty action man, ace investigator and sage with a neat sideline in homespun philosophy and cooking skills. His determination to brush off a deeply smitten Cyd Charisse for, let’s face it, some pretty spurious and unconvincing reasons is difficult to swallow. Then after assuring Stanwyck he is not in the business of wooing other men’s wives he proceeds to do just that before departing the scene again. I can’t fault Heflin’s playing but I have to scratch my head over some of the logic surrounding how his character is written. That said, I’m never displeased to see him in a movie and there’s no getting away from the fact that it’s not every day you have the opportunity to see him involved in a punch up with Beverly Michaels. Married to the producer Voldemar Vetluguin and making her screen debut, Michaels arrives fairly late in the story but is pivotal in bring about the resolution. And finally, there’s some well crafted support offered by Gale Sondergaard, Nancy Reagan (still Nancy Davis at this stage) and William Conrad.

East Side, West Side was released on DVD years ago as part of a Barbara Stanwyck box set by Warner Brothers so it shouldn’t be that hard to locate. There are undoubtedly better melodramas around but it has that MGM sheen that is certainly attractive, boosted by Mervyn LeRoy’s tight direction and a Miklos Rozsa score. The crime element lifts it in the latter stages and there’s a lot to be said for any chance to spend an hour and three quarters in the company of a cast as classy and accomplished as this picture boasts.