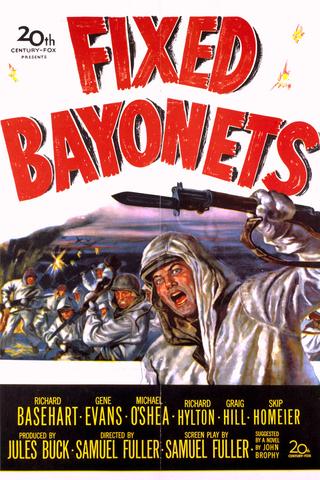

As I (not so) patiently wait for the new Sam Fuller box to roll up to my door I thought I might as well have a look at one of his other films to pass the time. It turned out to be a toss up between Forty Guns and Fixed Bayonets! (1951). Since I’ve been watching a lot of westerns lately and haven’t posted anything about war movies for a while it was the latter that won out in the end. This was Fuller’s first film for Fox, and it makes a nice companion piece to his earlier study of men in war The Steel Helmet – they’re both lean, unglamorous portrayals of the trials of enlisted men in Korea.

The plot is a very simple one – to cover the retreat of the division, a small detachment is left behind in the frozen wastes of Korea to carry out a rearguard action. This luckless group find themselves holed up in a narrow mountain pass, hoping to trick the Chinese into believing that they’re actually an advance party for the division. The focus is on Denno (Richard Basehart), a reluctant corporal who dropped out of officer training school because he didn’t want the responsibility. Not only that but he also has to deal with the fact that he finds himself unable to pull the trigger whenever he gets an enemy target in his sights. None of this would necessarily present a huge problem if it weren’t for the fact that Denno now has only three men between him and his greatest horror, the burden of command. In contrast to the sensitive, introspective corporal is Sergeant Rock (Gene Evans), the tough old pro who has stayed in the army but can’t quite put his finger on the reasons why. While the rest of the platoon have their doubts about Denno, Rock keeps faith with him as he feels he knows his man. As the Chinese press ever closer, and the casualties steadily mount, it’s obvious that sooner or later Denno will find himself the top man – the Ichiban Boy – and the only real question is how he’s going to handle it.

Gene Evans basically reprises his role from The Steel Helmet, but it’s almost the kind of part he was born to play. He really brings the battle-hardened Rock to life, full of fatalistic humour as he bullies and cajoles the grunts into doing what has to be done. If Rock is the beating heart of the platoon then Denno is the conscience, and Richard Basehart was well cast in that part. His quiet, dignified tone stands out among the casual slang of the other dog-faces around him. He was capable of that intense, repressed look that is ideal for a man being eaten up by inner turmoil. Some of the best scenes in the movie take place in the quiet moments in the cave when Rock and Denno chew the cud over the nature of soldiering and responsibility. Fuller directs these claustrophobic scenes with apparent ease, using a full 360 pan at one point to show the whole platoon (or what remains of it) looking on as the reluctant medic performs surgery on himself. He punctuates such scenes with bursts of jarring, unexpected violence and moments of incredible tension, such as Denno’s walk through a minefield at night to rescue a mortally wounded NCO. His sense of pacing and economy are spot on, with not a shot wasted as we rattle along to the climax.

The R1 DVD from Fox is a frugal affair with little in the way of extras but it does boast a generally strong transfer. Fixed Bayonets! is a fine early example of Fuller’s honest, no nonsense approach to film-making and has his unsentimental machismo stamped proudly all over it. I enjoyed it a hell of a lot – now if only that Sony boxset would turn up!