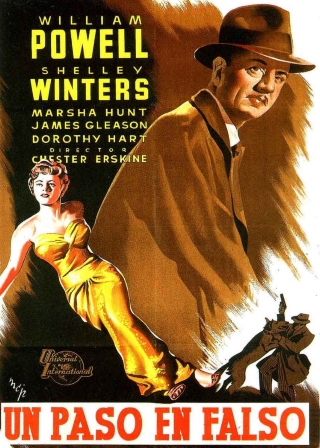

Any time I come across a mention of William Powell the name of Nick Charles springs to mind. The Thin Man and the series of sequels he made alongside co-star Myrna Loy represent only a fraction of his output, but it came to be something of a signature role for him. Those movies were enormously entertaining and Powell was perfectly cast in a part that allowed him to be smart, debonair and funny. Take One False Step (1949) came along much later, long after he had left Nick Charles behind, yet there is a hint of those light and stylish mysteries about it, easily as much as the film noir elements that its recent reissue might encourage one to believe to be dominant.

How much store should one set by the superficialities surrounding a film? I’m referring to the title, the credits, perhaps even the promotional material. The reason for posing that question is the fact that the opening credits for Take One False Step, and maybe the title itself, are strongly suggestive of some kind of late era screwball comedy. Of course all of this is emphasizing the need to remain vigilant, lest some major or minor catastrophe should befall one. The opening shot proper continues this theme, keeping the focus on a man’s feet as he enters a bar to order a drink before being addressed by some female counterparts. Well, it catches the attention. The man in question is Andrew Gentling (William Powell), a professor in the process of getting a new university off the ground. The woman who hails him from the bar is Catherine Sykes (Shelley Winters), an old flame he hasn’t seen in years, not since the war when both parties were unmarried and less burdened by life’s more mundane concerns. Should old acquaintances share a cup of kindness, or a couple of martinis at any rate? This pair do so and then part, as befits respectably married people. That ought to be the end of the matter, but Catherine is a restless type, pining for the immediacy of those dangerous wartime years, a woman prone to acting on her impulses. She calls Andrew up and invites him to a party, twisting his arm in a sense, but in a jokey, lighthearted way. Poor judgment, or momentary weakness, has been the undoing of many a noir protagonist and there is a whiff of that to Andrew’s acquiescence.

He soon discovers that he’s not only the guest of honor at this bash, but essentially the only guest. There’s nobody else present aside from another mutual friend Martha (Marsha Hunt) and she’s only there because her house happens to be the venue. Andrew is no longer the swashbuckler or adventurer Catherine remembers and perhaps he never really was, but he’s got a good heart and takes it upon himself to see the lady back home. She’s not so keen on this and he ends up taking a short stroll to let the fact sink in that there is to be no rekindling of lost romances on the agenda. Returning, he sees Catherine totter unsteadily back along the sidewalk towards her own place. However, that is only the beginning of the tale – the following morning brings news of Catherine’s disappearance, with only a bloody scarf, his scarf, left behind. Rather than go directly to the police, Andrew listens to some questionable advice and sets out to look into the business himself first. This leads to more trouble, with the cops, Catherine’s shady husband, a potentially rabid dog, and a race against time from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

Is it reasonable to say Take One False Step is a film noir? I wouldn’t use the term myself, though I understand how parts of the movie could attract such a legend. The setup does point in that direction, with the innocent man finding himself in over his head very quickly, and his actions and their effects achieving a nightmarish quality. Franz Planer’s cinematography fits the bill too, getting some real value from the everyday and unremarkable. In truth though, this is a straight up mystery, not that far removed from the kind of material William Powell was headlining back in the 30s when he was playing Nick Charles or Philo Vance. There is a touch of humor in it too, as that credit sequence suggests. It’s not overwhelming, simply lightening the mood on occasion and I can’t say I found it unwelcome. Those going in looking for an uncompromising noir picture may find it grating, but as I said that’s not the way to approach this movie. Chester Erskine was the director and he does good work, conjuring up some attractive compositions and keeping a handle on the pacing. Nevertheless, I think it would be fair to say his credits as a writer (Angel Face, Split Second) and as a producer (The Wonderful Country) are more significant than his assignments as a director.

William Powell simply oozed sophistication, ever graceful and charming regardless of how difficult a situation might threaten to become. This was his stock-in-trade, the foundation of his screen persona and he made use of it in almost every genre he appeared in. Yet he carried along with it a kind of wry awareness of the fact this was a persona, enabling him to look at himself, his fellow characters and the circumstances in which they find themselves with a knowing air. This worked well in classy comedies and he was able to blend it into his mystery roles too. I mentioned the part of Nick Charles at the top of this piece as I have a hunch that characterization will be more familiar to many readers, which is not meant to suggest it was his only notable role. I also referred in passing to Philo Vance and I imagine those who have seen him play that part might agree he was an ideal fit. Personally, I find that any time I read Van Dine I have the image of Powell in mind. As the hapless professor he is less in control of events than he was in some of those mysteries, but this affords him the opportunity to exploit those characteristics that made him attractive to viewers – that smoothly polished exterior with a hint of panic stirring beneath, but with good manners and restraint holding it in check. There is one particularly effective scene, full of grim humor, around the mid-point, where the professor is seriously concerned about a bite he suffered and has sought medical assistance from a grouchy doctor (Houseley Stevenson) who tests his patience, and that of the viewer, to the limit.

Shelley Winters was in some excellent movies around this time, in what I think of as her dissatisfied vamp period, before A Place in the Sun saw her get nudged towards playing more needy types. She brings a lot of energy to the early scenes before Marsha Hunt steps into the spotlight. Hunt, who passed away last year at the ripe old age of 104 and who was one of those almost hounded out of the business during the shameful HUAC episode, is the faithful best friend, a classic Girl Friday part which she embraces and excels at. As the lawmen on the trail of Powell’s fugitive academic, Sheldon Leonard and James Gleason are responsible for most of the humor. Leonard is his usual loud self, forever on the brink of exasperation, while Gleason provides another variation on that hard-bitten but likeable cop that he brought to both the Miss Withers and The Falcon series. Another notable supporting part is filled by the instantly recognizable Felix Bressart, in his last role. He had appeared with William Powell years before in the rather good, if rarely mentioned, Crossroads and specialized in playing the kind of quirky middle European types he takes on here.

Kino has been instrumental in rescuing a whole raft of Universal crime, noir and mystery pictures, titles that were hitherto either impossible to see or only available in dreadful beat up prints. Take One False Step has been included in one of their film noir boxes and while I see how there are traces of noir to be found, it really is more of a straight mystery with a few comedic touches here and there. I have to say I thoroughly enjoyed this film, it’s of a type that I find most appealing and the cast are uniformly excellent. I strongly recommend checking it out.