Films naturally reflect the times in which they are made, there’s no getting away from that. As an art form they of course focus on certain themes, frequently timeless ones at that, but there’s no divorcing the artistic ambition from the current circumstances. The western is particularly interesting in this respect as it uses a historical setting and period tropes to comment on a current situation. The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind, made back to back in 1966 by Monte Hellman, are a good illustration of this. Here are two films which could not have been made at another time; the mood and aesthetic are firmly rooted in the mid-60s, and in cinematic terms they look back to the classic era of the genre while also pressing forward and moving it in another direction. I see them as slotting in at the end of the genre’s transitional period, making them fascinating both historically and as an absorbing film experience in their own right.

The Shooting is as minimalist as they come with attention centered on just four people – Gashade (Warren Oates), Coley (Will Hutchins), Billy Spear (Jack Nicholson) and an unnamed woman (Millie Perkins). What’s more, precious little is revealed about the backgrounds of any of these characters; Gashade is referred to as having worked as a bounty hunter at one point, but that’s about it. Anyway, it matches perfectly the abrupt sparseness of the tale and the filmmaking style. As viewers we seem to arrive somewhere in the middle of the story, the events leading up to it being explained through a brisk flashback and the ongoing development of the narrative. In brief, the woman turns up and hires Gashade and Coley to lead her through the wilderness, without divulging exactly why she wants to travel or why she wants these men to accompany her. It gradually becomes clear that the events depicted in the flashback have a significant bearing on the woman’s motives, and then there’s the mysterious figure who follows all the way from a discreet distance. If anything, the lack of information and the way subtle hints are dropped as we go along cranks up the suspense. The film is virtually the antithesis of many current productions, where exposition seems to rule and everything has to be slavishly spelled out to audiences. By the time the startling conclusion rolls round almost as many questions have been raised as have been answered, yet the viewer is always treated as an intelligent adult capable of reading things in his or her own way.

Ride in the Whirlwind uses a more conventional narrative structure, and a slightly expanded cast, but it’s another pared down and deceptively simple piece of cinema. Once again no time is wasted in getting to the heart of the matter – a botched stagecoach robbery opens the movie in dramatic fashion and sets up the unfortunate circumstances into which three men will blindly stumble. Vern (Cameron Mitchell), Wes (Jack Nicholson) and Otis (Tom Filer) are cowhands heading back to Texas who unwittingly come upon the outlaw’s hideout. Sensing something amiss, they plan to ride on the following morning but everything goes awry when a trigger-happy posse shows up. As is the case in The Shooting, events overtake the men and force them into a situation where they have little control of their fate. In a sense this film offers a reversal of perspective; where The Shooting follows the action from the hunters’ point of view, Ride in the Whirlwind lets us see it all develop from the side of the hunted. There’s suspense too, but of a different kind – there’s no particular mystery to unravel and the motivation of all concerned is much more clear-cut and easily defined – as a tense struggle for survival ensues.

Aside from the common contributors – Hellman, Nicholson, Perkins and cinematographer Gregory Sandor in particular – both films are fatalistic, existentialist pursuit dramas. The characters are abruptly and without warning pitched into violent and desperate situations which they are powerless to avoid yet are also committed to seeing them through to the bitter end. There’s an authenticity there too in the spare, clipped dialogue. And then there are the Utah locations: barren, harsh and dusty, a remote and hostile environment where the human tragedies are played out and the land itself poses a physical challenge. So much of the imagery captured by Hellman and Sandor harks back to the classic westerns of the previous decade while the editing and oblique storytelling style is very much a product of the turbulent mid-60s, in fact it’s arguably ahead of its time. Anyone familiar with westerns will find countless nods to the films that went before and laid the groundwork – the dogged pursuit of the wrong men (The Ox-Bow Incident & The Bravados), the deliberate crippling of a gunfighter’s hand (The Man from Laramie, No Name on the Bullet, One-Eyed Jacks), the burning of the shack to flush out the occupants (Red Sundown), the sudden revelation of the hunter and his quarry’s identities (Winchester ’73) and so on. These are motifs that would crop up again in the future of course, attesting to the influential character of the films.

However, there are other factors which mark these productions out as being of their own era, and as forward-looking works too. For me anyway, a clear shift in tone has taken place. The late 40s and on into the 50s saw the world faced with its fair share of difficulty and uncertainty. Still, the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination and the massive social and cultural changes that were becoming apparent in the mid-1960s represented something totally different. Old certainties were being swept aside and consigned to a past that suddenly seemed very distant. Something new and, as is always the case when abrupt change occurs, vaguely unsettling was on its way; Hellman’s pair of westerns are a cinematic reflection of that sense of bewilderment and confusion.

And then there’s the matter of redemption, the mainstay of the genre throughout its golden years but something which would become increasingly rare with the passage of time. Gashade in The Shooting could be said to be on a redemptive quest, essentially chasing himself, or at least the darker side of himself, and perhaps achieving his goal in the end. I find it difficult to see how anyone else in that movie could be perceived in such terms though, and it just doesn’t apply at all in Ride in the Whirlwind. Therefore the altered emphasis in the western is more readily apparent in Hellman’s movies than was the case in other, earlier transitional works. The predominant feeling one comes away with, which is in marked contrast to what was to be found in the genre only a few years before, is ambiguity. While the true villains are easily identified, there’s a blurring or lack of definition when it comes to the heroes. Gashade’s inaction (albeit reluctant) effectively seals Coley’s fate and his subsequent assault on Spear could be seen as sentencing a man like that to certain death rather than genuinely sparing him. Similarly, when Vern and Wes break away from the homestead in Ride in the Whirlwind they cross a line ethically. The westerns that would follow, and not just the more nihilistic spaghetti variant, mostly saw the replacement of the hero with the anti-hero; a figure whom the audience could be asked to identify with but rarely admire, a figure whose moral plane was frequently only a degree or two above that of the villains.

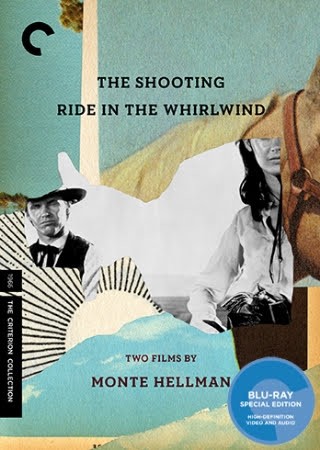

Frankly, these films always looked a little rough any time I’d seen them in the past on any home video format. I’m delighted to say though that the new release by Criterion, available on both DVD and Blu-ray, sees them looking exceptionally fine. Both titles have undergone 4K restorations with the blessing of the director and the results are very pleasing. There’s plenty of detail in the image and the colors are rich and natural, really showing off the starkly beautiful Utah locations. As usual with Criterion releases there’s a wealth of solid extra features offered: the booklet has an essay by Michael Atkinson, and the disc has interviews with various members of the cast and crew. Kim Morgan provides a video essay on Warren Oates, and there’s a conversation between Will Hutchins and Jake Perlin. On top of all that, both movies have commentary tracks with Monte Hellman, Blake Lucas and Bill Krohn, which are relaxed, entertaining and informative. Overall, it’s an excellent package with the two films looking better than I’ve ever seen them.

These are two fine westerns, entertaining, thoughtful, and made by a man who understood the genre. Furthermore, they’re important movies in the evolution of the western, adding another link to the chain which runs from the silent era right up to the present day. I suppose Ride in the Whirlwind would be the more accessible of the two for viewers unfamiliar with Hellman’s work, but both really are essential viewing for anyone with a taste for intelligent and original filmmaking. I highly recommend them.

My thanks to the people at The Criterion Collection for making this review possible.

Colin, thanks for reviewing these two westerns. I didn’t know Jack Nicholson had starred in a western and besides I have never seen him in any of his early movies. I think the earliest I ever saw him in was TERMS OF ENDEARMENT, 1983.

LikeLike

Nicholson was in, I think, five westerns but it’s not a genre you tend to associate him with. They’re excellent movie, Prashant, and you should keep an eye out for them.

LikeLike

Great stuff Colin – I’ve actually never seen either of these (for shame) – presumably the Criterion Blu-ray is region A locked?

LikeLike

Well, I was sent the DVD set as I understand the Blu-rays from Criterion are all region locked and I can’t play region A material. I certainly recommend the films – even casual western fans should get a lot out of them.

LikeLike

I skimmed your reviews because I will definitely get this release – thanks chum!

LikeLike

I tired to avoid too many obvious spoilers but that’s probably best if you plan to pick up the set.

LikeLike

You are always really good about avoiding spoilers but, although I keep thinking I must have seen one of these on the old Alex Cox Moviedrome series, I just don’t remember them at all so fancied a really fresh start. I got myself COCKFIGHTER but have yet to watch it – I’ve seen very little by Hellman actually …

LikeLike

I imagine you’re not alone in that – his critical reputation has been growing but most notably in recent years, I think.

LikeLike

I have been meaning to get the new release of these. Glad to hear they are looking good as previous copies have never been all that decent.

LikeLike

Definitely no complaints from me as far as the image quality is concerned, Mike. The two movies look very good.

LikeLike

Colin, I’m glad your bringing attention to these two important westerns by Monte Hellman. It may interest you to know, there was a photochemical restoration in 1999 followed by a screening at the American Cinematheque (the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood), which Monte Hellman and Millie Perkins attended. VCI released both films on DVD in 2000. Very nice transfers (although not up to the heights of these amazing 4K scans), with informative scene-pointed commentaries by Hellman and Perkins. The discs went out of print very quickly and the poor-quality public-domain releases took over. I wish the original commentaries had been carried over by Criterion. According to the original commentaries, the two films were written in January and February, 1965, entered pre-production in March and April, filmed back to back in May and June, edited over the summer, and turned over to Roger Corman in August 1965. The budgets were $75,000 each which is incredibly low. No wonder the cast doubled as grips.

Regarding The Shooting, Hellman remarks that although Gashade mentions his brother Coigne two or three times in the film, it doesn’t seem to register on audiences that the woman and her gunman are hunting Coigne. I think the confusion has to do with the name. When audiences hear Coigne, it doesn’t register, or perhaps they think it means something else. If his name had been Bob or Joe or Tom, the gist of the film might be clearer.

These are exceptional westerns, important westerns for all the reasons you describe. The films are so low-key, so different from what audiences expected from a western, neither film ever really found an audience. When they were re-released in 1971, to cash in on Jack Nicholson’s rise to stardom and Academy Award for FIVE EASY PIECES, I saw them in a near-empty theater. I was so impressed I went to see them a second time, again in an empty theater, which I noted in the journal I kept at the time.

LikeLike

Richard, they are certainly important films and ones which should be seen by all serious genre fans. I can well believe their originality set them apart at the time of release and arguably still does.

I haven’t heard the VCI commentaries but I feel the new tracks recorded by Hellman along with Bill Krohn and Blake Lucas are very fine, relaxed and informative pieces.

LikeLike

I couldn’t say exactly whether I like those Monte Hellman’s movies or not since they’re so different from any other westerns you could watch. Nevertheless, I watched them repeatedly. There’s a strangeness about them that makes ’em all the more fascinating. Nothing (I mean : nothing really spectacular) ever happens. Existentialist westerns, yes indeed. Meaning there’s no redemption anywhere nor any progress one could expect. Cinematography included, Monte Hellman’s movies look closer to Antonioni’s than to anything else you could think of. Seems like Hellman’s westerns sprang out of nowhere. Yet, you could trace them as far back as Budd Boetticher’s “Ride Lonesome” or “Comanche Station”, whose main characters played by Randolph Scott have a ghost like quality they share with Hellman’s characters. Just plain ordinary people having to deal with usual sufferings on a waste land. Which relates those unusual westerns (Boetticher’s as well as Hellman’s) to Albert Camus’ existentialist philosophy (i.e. life is absurd, meaningless, and Nature – so important in westerns – doesn’t care about man’s activities). Yes, you’re absolutely right Colin when you point out those westerns are deceptively simple. You could feel they just scratch the surface, with some kind of despise for the epic dimension of the western – which is not untrue -, just playing along with the western codes, superficially, but in fact they dig much deeper than many flashier westerns. How deep do they exactly dig? This I cannot tell…

LikeLike

I can well understand your rewatching the films; there’s something fascinating about them, the look, feel, story etc.

I do think The Shooting has a redemption aspect, albeit not as developed, or should that be not as readily apparent, as was the case in the 50s.

LikeLike

I avoided reading your excellent piece on this very fine Criterion package as I have never seen either of these films. I know that you don’t do spoilers but I wanted to approach the films knowing very little about them. They did get a very limited release in the UK in the Seventies to tie in with Nicholson’s superstar status at that time.

I must say that the films are presented in a wonderful way, the picture quality is stunning, to say the least. I would say this is an essential purchase for anyone interested in the development of The Western from the Sixties onward.

The extras are amazing and it’s hard to believe that both these films cost a mere (even by mid Sixties standards) $75,000 to make. Only gripe and it’s a really minor one, but in the interviews no-one mentions Cameron Mitchell. At the time he was the biggest “star” to get involved with these films. Aren’t those Kanab Utah locations striking.

I know it’s a far cry from his classic Westerns; but I would love to see Boetticher’s A TIME FOR DYING given this type of treatment.

LikeLike

Yes, the Criterion release really gives the movies a new lease of life. I’d only ever seen them in weakish transfers beforehand and was quite taken with how good they now look.

Sounds like you enjoyed the films, John. I’m not surprised by that though as they are fine pieces of work and ought to find an audience with most western fans.

LikeLike