I think it’s fair to say that the going always appears to be trickier once one hits the downside of a slope. There’s that ever present temptation to succumb to the lure of relaxation, to freewheel, to sit back and let the momentum carry one wherever it fancies. If we are to see the western as having scaled the heights of its artistic potential by the end of the 1950s, and on into the beginning of the next decade to be fair, then the following years must represent the other side of that hill. By the mid-60s the treacherous nature of that downhill path was becoming apparent, the more so since it proved to be a pretty steep descent for the most part. As the decade wore on there were increasing numbers of westerns that do not quite work, or which flat out fail in some cases. It can be a dispiriting experience trawling through some of these when one bears in mind what had come before. Still, one of the strengths of this genre is its overall resilience, its ability to offer up something worthwhile just when it seems that hope has passed. The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) is not what I would personally term a great western, but it is a very good and entertaining one.

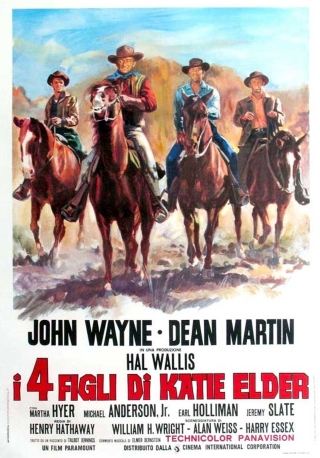

The plot of The Sons of Katie Elder follows a well trodden path. A newcomer buys influence and expands his power, elbowing aside any local objections or stamping hard on them should the need arise. In the case of the eponymous Mrs Elder and her offspring, the latter action appears to have been applied. We never get to see Katie Elder, she has already passed away before the movie begins and the opening scene has three of her sons, Tom, Matt and Bud (Dean Martin, Earl Holliman, and Michael Anderson Jr respectively) waiting by the train halt for the senior member of the clan to arrive prior to attending the funeral. The oldest brother John Elder (John Wayne) is a gunfighter of renown or ignominy, depending on one’s perspective. Well he doesn’t show up so the service takes place without him, or so it seems. The fact is he has slipped back home unobtrusively and we can observe him watching proceedings from afar, high among the rocks overlooking the cemetery, aloof and vaguely forbidding in his isolation. As the story progresses, it becomes evident that the Elder family has been cheated, the father was almost certainly murdered and his wife then forced to leave the home where she raised her four boys before they went on their separate ways. Now they are back though and experiencing a combination of guilt for their neglect of a woman who everybody held in the highest regard as well as an incipient sense of indignation over being gypped. And that’s how it plays out – the process of arriving at some kind of accommodation with feelings of self-reproach develops side by side with a deepening conflict with Morgan Hastings (James Gregory), the man now occupying the land that was once theirs.

The notion of past events coloring or shading the present frequently results in good drama, and the shadow of Katie Elder looms large in the lives of her sons. Where each of them is seen to be flawed or negligent or profligate, their mother is spoken of with warmth and respect by all those who had known her. This conceit is a neat way to allow the characters to address their own deficiencies within a narrative framework which encompasses justice and redemption. Having Katie exist only as a memory offers the opportunity to build something of a myth around her, as of an ideal to be lived up to. By rendering her in those terms her spirit starts to feel emblematic of the mythical west, almost as though woman and land have fused. It’s an aspect that is further highlighted when Martha Hyer speaks of her to the four sons as all of them stand around the old lady’s beloved rocking chair.

Texas is a woman, she used to say, a big, wild, beautiful woman. You raise a kid to where he’s got some size, and there’s Texas whispering in his ear and smiling, saying, “Come and have some fun.” “It’s hard enough to raise children,” she’d say. “But when you’ve got to fight Texas, a mother hasn’t a chance.”

The Sons of Katie Elder was John Wayne’s first film after undergoing major surgery for lung cancer. He’d had a lung and a couple of ribs removed only a few months before but looked and acted remarkably robust under the circumstances. It’s an ebullient performance, big and commanding with the balance between humor and seriousness deftly maintained. Henry Hathaway framed and shot him in such a way as to emphasize the iconic, monumental stature he was growing into by this time. Some of the action scenes are very stylized, but superbly put together at the same time – the big gun battle at the river crossing, and that memorable moment when he belts George Kennedy’s sniggering bully full in the face with an axe handle.

Dean Martin made his western debut alongside Wayne in Rio Bravo, giving a fine performance first time out and growing ever more comfortable in the genre in subsequent outings. Maybe he became too comfortable at times later on, cruising along on charm and a wink at the camera. His role as Tom Elder allows him to indulge the laid-back persona at times – a nicely played comedic interlude in a saloon involving a glass eye, as well as some other horseplay involving his siblings – but not to the extent is diminishes the more dramatic moments. Earl Holliman is quite subdued, much more composed than some of the less secure characters he was often cast as. The youngest brother was Michael Anderson Jr and he was enjoying a wonderful run in westerns that year; aside from The Sons of Katie Elder, he had roles The Glory Guys and Major Dundee. One notable feature of this movie was the absence of any other women bar Martha Hyer, who serves as a kind of conscience for the the Elders, recalling the strong character of the late Katie and reminding the sons of their duty to her memory. It’s worth pointing out too that the movie represented a rehabilitation for Dennis Hopper. He had apparently enraged Henry Hathaway during the making of From Hell to Texas and found himself essentially frozen out in Hollywood till Wayne got him the part in this film. Of course he would go on to work with Hathaway, and an Oscar winning Wayne, once more a few years later on True Grit.

The Sons of Katie Elder is what I’d call a satisfying western, something that was not the case with a number of genre efforts as the decade wore on. Hathaway’s films were always very smoothly put together and this one is no exception. Basically, he keeps everything balanced; the classic western themes are there, the cast features a lot of very familiar faces who are used sparingly and not in the tired “by the numbers” fashion of, say, an A C Lyles picture, Lucien Ballard has it looking extremely attractive and Elmer Bernstein’s score is one of his better ones. All in all, this is a very watchable and enjoyable film.