Just wanted to let readers know that Brian at Rupert Pupkin Speaks has been running a feature on underrated westerns recently and getting contributions from various bloggers. Anyway, he asked me if I’d like to submit some for consideration. I was pleased to do so, and you can see my selection here. While you’re there it’s worth looking through the choices others have made – I think the series is a great idea.

Author: Colin McGuigan

Angel Face

I don’t pretend to know what goes on behind that pretty little face of yours; I don’t want to. But I learned one thing very early. Never be the innocent bystander; that’s the guy that always gets hurt.

The femme fatale, the deadly woman, the one whose duplicity, self-interest and machinations lure the protagonist towards danger and doom is widely considered to be a staple of film noir. I’ve even seen some argue that such a figure is an essential element of this style of filmmaking, though I wouldn’t go as far as that myself. And yet she is an important figure, one who has achieved iconic status and entered the everyday vocabulary of even casual film fans. There have been outstanding examples of the femme fatale committed to film: Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, Jane Greer in Out of the Past, Ava Gardner in The Killers and Yvonne De Carlo in Criss Cross to name just a handful of notables. Those women were all devious, alluring and lethal, and all of them were entirely conscious of their inherent malice. But what of those characters who fall almost accidentally into the category of the fatal woman? What if a woman, by her actions, becomes a femme fatale while her motivations and psychological profile are wholly different? As far as I can see, Angel Face (1952) provides an example of just such a case – a dangerously attractive female of deadly intent who’s also a mass of complexities and contradictions.

An ambulance is called to a Beverly Hills mansion late at night. Catherine Tremayne (Barbara O’Neil), the owner, has almost died in a gas-filled bedroom. It might have been an attempted suicide or an attempted murder, but in the end everyone seems satisfied that it was probably just one of those unfortunate accidents that occur in the home. With the emergency apparently over and people about to head home, Frank Jessup (Robert Mitchum), one of the ambulance drivers, pauses in the hallway, his attention caught by the figure of a girl at the piano in the drawing-room. This is Diane Tremayne (Jean Simmons), the owner’s stepdaughter. As Frank stops to offer a word of reassurance, we get a glimpse of the fragile instability of the girl; she’s edgy and prone to hysterics. But more than that, there’s an impulsive, neurotic side to her. The former is immediately apparent when she follows Frank and essentially picks him up as he ends his shift. The latter, the neurosis, is revealed more gradually as she sets about seducing Frank and drawing him ever deeper into the complicated affairs of the Tremayne household. Diane’s father (Herbert Marshall) is – or rather was – a celebrated writer who has let his talents go to seed, mostly as a result of the pampered lifestyle brought on by a comfortable marriage. In Diane’s eyes her father is, and always will be, her whole world. As such, Catherine is the enemy, the cause of her father’s creative decline and her own consequent dissatisfaction. Almost every noir scenario revolves around the weakness of the protagonists, often their inability to accept responsibility for their own situation in life. And so it is with Diane, everything could be hauled back onto an even keel if only Catherine weren’t there: her father would recover his desire to write and she would be free to make a life with Frank. However, fate has an unfortunate tendency to throw a big awkward spanner in the works and even the best laid plans can go disastrously awry.

It’s very often the case that the most compelling movies had a troubled production history. I don’t know whether it’s down to behind the scenes tensions lending an air of urgency to events on the screen or the people involved becoming more focused on their task. Either way, there are plenty of examples of a poisonous atmosphere bringing about a fine movie. With Howard Hughes in charge of RKO there always seemed to be ample opportunity for discord on the set. Angel Face was essentially a film born of pettiness. Hughes wanted Jean Simmons but she’d recently married Stewart Granger and was having none of it. The upshot of all this was Simmons struck a deal to make a handful of films quickly and thus get out of an unpleasant contract. Her dislike of Hughes and his unwelcome attention was so great that she even chopped off her hair crudely and so was forced to play her role in the film with a slightly odd-looking wig. On top of all that, there were issues with director Otto Preminger. Simmons’ first scene in the picture involved her descending into hysterics and Mitchum bringing her out of it with the application of that cinematic staple, the open-handed slap. Well Preminger apparently didn’t like the way Mitchum pulled the blow, claiming it was going to look phony in close-up. So he had him do it again, and again, and again. With Simmons in tears and Preminger relentless, Mitchum apparently turned on the director and either gave him some of the same treatment or threatened to do so – for more on the tumultuous production, see Robert Mitchum: Baby, I Don’t Care by Lee Server pp 288-291. Maybe nobody was having a particularly good time on the set but the end result was the taut, highly strung atmosphere of the Tremayne house and that feels completely authentic.

Angel Face is Jean Simmons’ picture all the way, and gave her one of her most interesting and complex roles. As I said in the introduction, she’s unquestionably the femme fatale of the film, her actions causing chaos, death and misery. Yet she brings an emotional immaturity and insecurity to the part that sets Diane Tremayne apart from the classic interpretation of the femme fatale. If her behavior is seen as selfish, then it’s only a childish form of selfishness. Her hatred for her stepmother only exists as a result of her love and devotion for her father, and her ultimate destruction of Frank is an unwanted side-effect – there’s no malicious calculation involved. Where Simmons really excelled was in her portrayal of the brittleness of the character; her every gesture is suggestive of a young woman tiptoeing around the rim of a moral abyss. Mitchum of course was a past master by this stage at playing the kind of weary types who had bid farewell to hope long ago. The deceptive sleepiness and detachment he’s often accused of perfectly suits the character here – a disillusioned veteran half adrift in a world that he only thinks he’s got a handle on. The supporting cast all do fine work too, the highlights being: Herbert Marshall’s dissipated joviality, Barbara O’Neil’s cool take on the society matron, and Leon Ames as the twisty, unctuous lawyer.

Angel Face is available on DVD via Warner Brothers in the US, and the disc sports a very nice transfer. Everything’s crisp and clean and Harry Stradling’s cinematography always looks good. The DVD also carries a commentary by noir specialist Eddie Muller. Otto Preminger’s noir films are all worthwhile, classy efforts. This one may have had something of a sour background but what we see on screen is hard to fault. For me, the performance of Jean Simmons in a difficult and demanding role is the best thing about it all, but that’s just the icing on the cake. I reckon it’s a must see film noir.

A Distant Trumpet

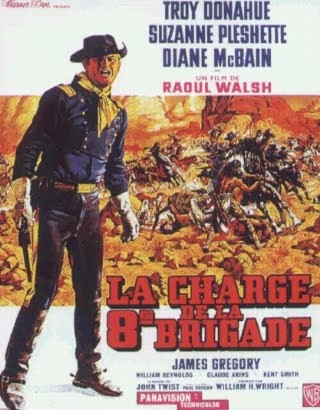

It’s been remarked on before how the 1960s saw a gradual change in approach adopted by the Hollywood western. And it was indeed gradual, up until the middle of the decade, and even a little further in some cases, the influence and sensibilities of the 50s could still be discerned. The change, when it did come, tended to be most marked in the work of the newer breed of directors. The old hands, the pioneers, remained closer to the traditional vision and portrayal of the west. Raoul Walsh, with his earliest directing credit stretching way back to 1913, was most assuredly of the old school, and his final film A Distant Trumpet (1964) has more of the feel of a 50s western than one from the mid-60s.

The film opens spectacularly with a clash between the massed forces of the US cavalry and the Apache. It then cuts swiftly to the academy at West Point where General Quait (James Gregory) is delivering a first hand account of those events to a class of cadets. Among his audience is a young lieutenant Matt Hazard (Troy Donahue), soon to be posted to the remote and undermanned Fort Delivery in Arizona. It’s through Hazard’s idealistic and ambitious eyes that the remainder of the story is seen. The slovenliness, incompetency and insubordination he encounters at the isolated outpost is an affront to the young man’s sense of military propriety. As he assumes the task of whipping the rag-tag detachment into something resembling a modern, disciplined fighting force we get a look at the day-to-day lives of cavalrymen that, in some respects, recalls the work of John Ford. Woven into this is a, not altogether successful, romantic subplot which sees Hazard torn between his betrothed, the General’s niece Laura (Diane McBain), and Kitty (Suzanne Pleshette), the wife of a fellow officer. The second half of the movie sees General Quait and his troops arrive at the fort, and the emphasis shifts to the military campaign to neutralize the threat posed by the renegade Apache War Eagle. Quait’s tactics prove only partially effective however, and achieve not much more than driving War Eagle back across the border into the safety of Mexico. Holed up somewhere deep in the Sierra Madre, War Eagle is at liberty to raid over the border whenever he feels like it. Unless of course someone is prepared to risk his neck going alone into the Apache stronghold to negotiate terms with the old warrior. All told, the latter half of the movie works a lot better, not least because the unsatisfying romance is sidelined for long stretches. Not only are action and spectacle brought to the fore, but there’s greater opportunity to highlight the inherent pro-Indian sympathies of the film.

Raoul Walsh brought a lifetime of experience to the shooting of A Distant Trumpet, and the staging of some of the later battle scenes has an epic quality, aided by the wonderful camerawork of William Clothier. Walsh was always a first class director of action, and location work suited his talents especially well. The wide lens is used very effectively to highlight the vastness of the landscape and, again in a way reminiscent of Ford, the relative insignificance of the tiny humans framed against the primal backdrop. It’s easy to forget though that Walsh had a flair for close-ups and more intimate composition too, and the film offers plenty of chances to sample that aspect of his skill. One of the other great strengths of the production is the score; Max Steiner’s pounding, martial theme adds drive to the film and powers it along. And that brings us to the script, so often the crucial factor when it comes to making or breaking a film. The basis for the movie is a novel by Paul Horgan (not having read it, I can’t comment on how true the adaptation is) and the script derived from this reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of the finished product. To begin with the positives: the story told is in effect an account of the latter stages of General Crook’s campaign against the Apache, and Geronimo in particular. Right away we have both a compelling narrative and, just as important, a chance to cast a critical eye over government/army relations and policy towards the Indians. The script treats the Apache with the greatest respect – not phony sentimentalism or misplaced adulation – and adopts a mature and balanced stance. There’s no shying away from atrocities, nor is there any attempt to gloss over government hypocrisy and the shabbiness of broken promises. One could, I suppose, complain about the positive resolution that doesn’t take into account how events really played out, but overall the film pulls no punches in its portrayal of the situation. As for the negatives, the aforementioned romance, and consequent soapy elements, isn’t very well realized. It would appear to exist primarily as a means of fleshing out the character of Lt Hazard, however, it actually only serves to bog the picture down and dampen the pace in the first half.

I think of Troy Donahue principally as the star of 50s and 60s soap dramas. I understand his performance isn’t all that well regarded in A Distant Trumpet, but I’ll break ranks here and say that he’s reasonable in certain scenes. He fares best in the latter stages where he’s called on to play the action hero for the most part. His deficiencies are far more noticeable in the intimate scenes though, and that makes the romantic stuff seem even more labored. I guess it doesn’t help any that the parts of Suzanne Pleshette and, more especially, Diane McBain are pretty much under written. Pleshette has the stronger, more sympathetic role, while McBain gets to look glamorous but is saddled with playing a stuck-up, unattractive character. To be honest, McBain’s part could have been cut from the movie and not harmed the narrative one iota. James Gregory is very entertaining and seemed to enjoy playing the Latin-quoting general. Every scene he’s in is all the better for his presence. Claude Akins is good value too as the Indian agent, and purveyor of anything and everything from whiskey and guns to loose women. Generally, the supporting cast is fine with small but memorable roles for Kent Smith, Judson Pratt and William Reynolds.

A Distant Trumpet is widely available these days via the Warner Archive and various European releases. I bought the French Warner Brothers DVD back when it was the only edition available. That’s more than a few years ago now but the transfer still stands up well in my opinion. There’s a nice, crisp and colorful anamorphic scope image that’s basically undamaged. French DVDs can be troublesome when it comes to subtitles, but I don’t think I’ve ever had any issues with Warner releases. The subs are easily disabled via the language menu on this one. All in all, the film is what I’d call sporadically successful; there’s a strong story in there with a message that’s subtly expressed and never feels forced. On the other hand, there’s flab in the script too that could and arguably should have been edited out. There’s an ambition to achieve something approaching the epic, but the scripting and some of the casting choices fall short. However, while I have some reservations, I feel the movie works reasonably well on the whole.

The Suspect

A man trapped in a hellish domestic situation and driven over the edge by intolerable circumstances, challenged by a hydra-like fate at every turn. It sounds very much like a typical noir scenario, doesn’t it? Well, swap the glare of neon on rain-swept sidewalks for the soft glow of gaslight on damp cobblestones and it becomes apparent that The Suspect (1944) is indeed classic film noir. The setting may be Edwardian London but the moral dilemma confronting the protagonist leaves no doubt as to what category the movie falls into.

Philip Marshall (Charles Laughton) is essentially a nice guy, we’re reminded of this again and again throughout the film. He’s first seen on his way home from his job in a London tobacconists, pausing outside his front door to exchange pleasantries with his neighbor. As he enters his home though it becomes immediately apparent that all is not as it should be in his personal life. His bitter and acid-tongued wife Cora (Rosalind Ivan) informs him that their only son is moving out; a temper tantrum and the ensuing actions of Cora having proven to be the final straw for the boy. Marshall himself accepts the news calmly enough, it’s nothing he hasn’t been expecting though it also acts as something of a watershed as far as his own attitude to the marriage is concerned. Exasperated by Cora’s shrewish behaviour, Marshall moves into his son’s old room and seals what amounts to a de facto separation. The situation is reinforced, and is moved onto another level, when he meets Mary Gray (Ella Raines). As these two lonely people gradually embark on a relationship, the first instance of the film’s ambivalent morality comes to the fore. Essentially, Marshall and Mary are indulging in infidelity yet the seemingly chaste nature of their relationship, coupled with the not insignificant fact that both of them appear genuinely happy in each other’s company, encourages us to view it in a wholly sympathetic light. Matters are muddied still further when Cora’s poisonous nature threatens Mary’s future, even though Marshall has reluctantly agreed to end the affair. Everything heats up from this point as Marshall finds himself facing a dilemma, and the only solution he can see is the removal of Cora. Again, our moral sense tells us that this is wrong, and again the vile spitefulness of Cora ranged against the likeability of Marshall (and Mary) means the viewers face their own ethical quandary.

The Suspect though is an extremely clever piece of filmmaking, and the decision not to show the murder actually taking place is a further example of its deft manipulation of the audience. By taking this approach, the movie leaves at least a seed of doubt in our minds – it almost feels like it wants to encourage us to believe that Marshall may not really have done away with Cora. Thus far we’ve seen a dysfunctional marriage, an apparently doomed romance, infidelity and murder. However, before the credits roll blackmail, the persecution of the innocent and the possibility of some kind of redemption are all stirred into the mix. I won’t go into details regarding the ending here, but I will say that I felt it adopted a nice ambiguous tone, one that is entirely appropriate given all that’s gone before. Personally, I consider it another example of the film’s skill in sidestepping the strictures of the Hays Code – the door remains open (albeit by only a hair’s breadth) for the kind of resolution the moral guardians of the time would have certainly frowned upon.

Robert Siodmak remains one of the most important figures in the development of film noir throughout the 1940s. His work, taken as a whole, would serve as a pretty good introduction to this style of filmmaking, and his movies are easily up there among my favorites. He started off his noir cycle quite brilliantly with Phantom Lady and then moved on to the odd and unsettling Christmas Holiday. The latter film began to explore the corrosive effects of an unconventional family dynamic and The Suspect continues this focus on troubles in the home, although from a different angle. In fact, Siodmak would go on to expand on this theme in his next noir project too, The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry; the films actually have some elements in common, namely Ella Raines turning up to charm lonely men trapped by suffocating domestic arrangements. Much of the movie is consequently shot indoors, particularly in Marshall’s home, and makes good use of the atmospheric set design that was typical of Universal productions. I mentioned before that Cora’s death is never shown, but there is a marvelous sequence where the dogged detective, Inspector Huxley (Stanley Ridges), visits Marshall and reconstructs the crime. The whole thing takes place on the staircase with Marshall at the foot and Huxley enveloped in the shadows on the landing. As Huxley narrates his theory as to how events may have played out, the detective is literally absorbed into the darkness and the camera darts back and forth between the positions he imagines Marshall and Cora occupied. While it only lasts a few minutes, it really draws you in and neatly highlights the flair and artistry of Siodmak.

Charles Laughton was one of those larger than life actors who was forever in danger of overcooking a performance – anyone who has seen Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn will know exactly what I mean – but could also display great subtlety when handled correctly. Siodmak seems to have reined him in successfully and the result is a finely nuanced portrait of a man resigned to a life of disappointment who’s offered a glimpse of fulfillment. A character such as Philip Marshall could quite easily fall into the villainous category, and it’s to Laughton’s credit (with the assistance of that clever script) that he remains such a sympathetic figure at all times. Of course the fact that Laughton found himself paired off with Ella Raines doesn’t hurt either. At first glance Laughton and Raines make for an unlikely couple. Still, it works on screen, and Raines’ ability to project her particular brand of alluring loyalty (a quality Siodmak clearly recognized and exploited very well in their three collaborations) plays a significant part in that. Rosalind Ivan’s role as Cora is a thankless one in that her character honestly has no redeeming features; every time the audience might feel some vague stirring of sympathy she quickly reverts to type. Nevertheless, as a textbook example of bile and vindictiveness, it’s remarkably effective. The real villain of the piece, the man who elicits the most antipathy, is Henry Daniell. He pretty much built an entire career on playing slimy, scheming ne’er do wells and The Suspect offered another opportunity to get his teeth into such a part. He’s supercilious, unscrupulous and self-absorbed – a character it’s uncommonly easy to despise. And finally, a brief mention for Stanley Ridges. Always a reliable presence in any film, Ridges brings a calm authority to his performance as the detective who appears almost reluctant to do his duty.

Some of Siodmak’s noir pictures have proven pretty difficult to see over the years, though the situation has improved somewhat. The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry is currently only available in fairly poor quality (although a pretty good print has been broadcast on TV) but it seems to be earmarked as a future release by Olive in the US. The Suspect is another of the elusive ones; it was released on DVD in Spain a few years back and I was lucky enough to pick up a copy. That edition now seems to have gone out of print, although there do appear to be copies still available. There’s also an Italian release but I can’t comment on that – I do have a few other titles by that company though and have had no complaints thus far. The Spanish DVD is taken from an unrestored print – there are small scratches, cue blips and the like – but it still looks quite nice. The contrast, always important when it comes to noir, is fine and the film has been transferred progressively. There is a choice of the original English soundtrack or a Spanish dub. Also, there are no problems with subtitles – they’re optional and can be disabled from the setup menu. As a fan of Siodmak’s work, I like the film a lot. There is a certain amount of melodrama on show but it’s of the attractive noir variety. Laughton is excellent and admirably restrained, and the presence of Ella Raines is very welcome. Most of all though, I enjoyed the way the tale manipulates and subverts our notions of morality. Overall, it’s a quality entry in Siodmak’s noir series and recommended viewing.

The House of the Seven Hawks

The House of the Seven Hawks (1959) has a potentially interesting premise. There’s an American charter boat skipper with a laid-back approach to the law operating out of a foreign port, which straight away recalls Harry Morgan in Hawks’ To Have and Have Not. There’s a trio of shadowy figures – a fat man, an effete and prissy assistant, and a none too smart bodyguard – plotting on the periphery, so it’s hard not to be reminded of Huston’s The Maltese Falcon. Naturally, we also have a brace of females whose motives and loyalties are difficult to pin down. Such a setup promises much, but the movie itself delivers only sporadically.

John Nordley is scratching out a living on the English coast, hiring out his boat for charter. Despite not having clearance to leave British waters, his latest client – an elderly Dutchman going by the name of Anselme (Gerard Heinz) – promises a fat reward if Nordley will run him as far as the Netherlands. Bearing in mind the money involved, Nordley reckons it’s worth the risk and agrees. Unfortunately, just as the vessel is in sight of its destination, Nordley finds that his passenger has passed away in his cabin. A quick search reveals that Anselme had a kind of crude map overlay taped to his body. Sensing it could be important, Nordley appropriates the document, and his suspicions are borne out when a young woman in a motor launch (Linda Christian) turns up purporting to be the deceased’s daughter. Not finding the document, she quickly takes off, and events move pretty fast at this point. It turns out that the dead man was in reality a member of the Dutch police traveling incognito and the document is sought by those on both sides of the law. As such, Nordley has stumbled into a murky situation where everyone seems to know a whole lot more than he does, yet his cooperation, or at least his apparent knowledge of the whereabouts of the map key, is in great demand. What it all boils down to is a hunt for missing Nazi loot, and Nordley has his hands full trying to stay one step ahead of the police, criminals and duplicitous women.

Adapted from a Victor Canning novel, The House of the Seven Hawks flatters to deceive. As I mentioned above, all the ingredients would seem to be in place for an intriguing little thriller. And yet it never really sparks into life. Richard Thorpe’s direction is passable enough, and the location work in the Netherlands is attractive. Still, with the exception of a handful of scenes it all looks a bit nondescript. This kind of tale cries out for some moody or interesting visuals to generate or accentuate the suspense and mystery elements, but that rarely happens. However, a bigger problem is the script. I haven’t read Canning’s novel so I can’t say whether the fault lies with the source material or Jo Eisinger’s adaptation. Either way, the fact remains that the pace fades once the action moves to the Netherlands. The movie runs for around 90 minutes and I think it could have been a better piece if a bit of trimming had been done. There’s too much talk and a lot of it’s pretty dull to boot.

What kept my interest in the movie alive was mainly the presence of Robert Taylor. He’d had a great run in the movies throughout the 50s and had some first-rate work under his belt. His role here as the skipper with a fondness for bending the rules when the price was right seems like a good piece of casting. In truth, he doesn’t disappoint, although the part fails to offer the depth or complexity that played to his strengths as a performer. It’s Taylor’s sardonic and cynical delivery of some pretty banal dialogue that just about keeps the whole thing afloat though. At first, I thought that Linda Christian’s femme fatale was going to provide the movie with a much needed lift, but she’s given far too little to do and disappears far too soon. Which means that there’s more screen time for Nicole Maurey, but her character is a lot less interesting. As it happens, I recently watched Ms Maurey in Robert Hamer’s The Scapegoat, where she was handed a far better role. Eric Pohlmann and David Kossoff played the principal villains, the latter adding a touch of quirky humor, but it has to be said they don’t manage to create the necessary degree of menace; there’s never the feeling that Taylor won’t be able to handle this pair. The other supporting roles of note are filled by Donald Wolfit and Philo Hauser.

The House of the Seven Hawks is a film I’d never seen until I picked up the DVD a while back. It’s available in the US as part of the Warner Archive and as a pressed disc in Italy. I have that Italian release and I have to say it presents the film nicely. The image is 1.78:1 and generally looks fine, without any noticeable print damage and it’s pretty sharp throughout. There’s the option to watch the film in English either with or without Italian subtitles and an Italian dub is also available. Extras consist of the trailer and a gallery. So, how does the movie stack up overall? Personally, I have a soft spot for thrillers of this era and anything with Robert Taylor is always welcome. Having said that, there’s no getting away from the fact that the movie doesn’t represent the best of either. In all honesty, there’s nothing here that hasn’t been done elsewhere, and done better.

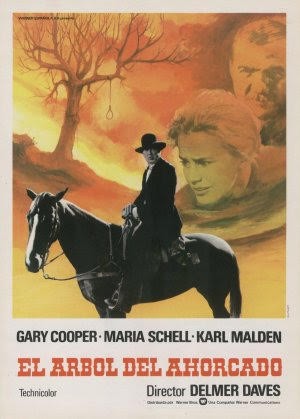

The Hanging Tree

I came to town to search for gold

And I brought with me a memory

And I seemed to hear the night winds cry

Go hang your dreams on the hanging tree

Your dreams of love that will never be

Hang your faded dreams on the hanging tree. – Mack David & Jerry Livingston

Redemption and its near relative salvation are in many ways the cornerstones of the classic western. These twin themes recur throughout the genre and lie at the heart of all the great westerns. Allied to these concepts is the notion of spiritual rebirth, the discovery of that indefinable something which serves to draw lost and damaged souls back from limbo. The Hanging Tree (1959) successfully explores all these elements and is a beautifully constructed piece, cyclical and symmetrical, and rich in the kind of life-affirming positiveness that I’ve come to see as one of the integral aspects of director Delmer Daves’ western work.

Montana 1873, the lure of gold has drawn all the flotsam and jetsam of humanity to the territory in search of riches. It’s a nomadic, rootless life for those following the gold trail, traipsing from one settlement to another as the hopes of making that big strike ebb and flow. Joe Frail (Gary Cooper) is one of those drifting through the west, although his motives appear less certain. Frail is a doctor, and seems more interested in the opportunity to keep on the move than in any desire to become wealthy. Newly arrived in yet another shanty encampment that has sprung up around the prospectors’ claims, Frail has no sooner secured a place to stay than he finds himself saving the life of a young man. Rune (Ben Piazza) is a sluice robber, attempting to snatch nuggets from the workings, and running from a trigger-happy lynch mob. Frail takes him in, treats his wound, and keeps him on as a bonded servant in lieu of payment. Thus we have the first instance of salvation, Frail protecting Rune from the hanging tree which he eyes with an air of fatalism at the opening. As the doctor sets up practice it’s gradually revealed that this laconic and reserved man has a shadowy past and a reputation as an accomplished gunman. The second person to be saved is a Swedish immigrant Elizabeth Mahler (Maria Schell), the sole survivor of a stagecoach robbery. Suffering from exposure and temporarily blinded, Elizabeth is found by Frenchy Plante (Karl Malden), one of those amoral types that exist around gold camps, and nursed back to health by Frail. It’s at this point that the story becomes most involving. Prior to this there were only hints and oblique allusions to the doctor’s inner pain. Frail is a man buried in the past, emotionally entombed and haunting the world of the living rather than actually participating in it. As Elizabeth’s affection for Frail slowly blossoms into love, the doctor draws back and distances himself. Elizabeth’s confusion is shared by the viewer as it’s apparent that Frail is attached to her but unwilling or unable to take the leap of faith necessary. The reasons for this hesitancy masquerading as indifference do become clear as the tale progresses, but it’s only when Frail is also dragged before the hanging tree that a resolution is achieved. The film’s powerful and emotive climax sees the hero’s protective yet stifling armor stripped away and the ultimate redemption, salvation and rebirth realized.

Delmer Daves made some of the finest westerns of the 1950s and it’s only fitting that he should round off the decade with a work as layered, sensitive and complex as The Hanging Tree. As I said in my introduction, the structure of the film is carefully judged. Not only is it book-ended by Marty Robbins’ wonderful rendition of the title song, but it also opens and closes with the figure of Cooper, having undergone a major spiritual reawakening over the course of the story, beneath the hanging tree. The film is packed with symbolism, fire and trees being the most prominent. In both cases, we are encouraged to view these elements in a positive and negative light. Fire is initially referred to, though not seen, as representative of Doc Frail’s traumatic past. When it appears again near the end though it takes on a cathartic quality, burning away the negativity which has dogged him. And of course the focus on trees is even more significant. There are two trees of note: the hanging tree of the title and the one overlooking Elizabeth and Frenchy’s claim. The former naturally calls most attention to itself; the gnarled, clawing branches suggestive of guilt, punishment and death. And yet by the end it comes to symbolize something entirely different – renewal, permanence and the birth of a new life. That other tree, the one which eventually falls into the river, has to be viewed as a positive feature too. It’s destruction of the claim reveals the treasure hidden among its roots, the cache of nuggets which will both precipitate the final confrontation and eventually liberate the characters. Aside from all this, the location shooting and the camera positions of Daves and cinematographer Ted McCord also help focus on the subtext. The fact that Frail chooses a home high on a cliff above the swarming anthill of the mining camp serves to emphasize the remoteness and distance of the character.

Gary Cooper was an ideal piece of casting as the taciturn and aloof Joe Frail, his weathered features perfectly reflecting the emotionally desiccated man he was portraying. It’s not uncommon to read critical comments about Cooper’s acting, often failing to appreciate the subtle and understated nature of the man’s work. As with all the great screen actors, Cooper understood and used the little things, the twitch of a facial muscle or the quick glance that reveal more than pages of dialogue and overt emoting ever could. It’s not the first time that the point has been made that a good western is so often elevated by the presence of a strong female role, and Maria Schell’s performance in The Hanging Tree provides a good illustration of this. Frankly, she hardly puts a foot wrong at any point, from her initial helplessness and vulnerability, through the confusion prompted by her rejection, to her eventual emergence as an independent and complete woman. If the movie is really about Frail’s journey I think it’s also fair to say that it would be a meaningless and hollow affair had it not been for the strength of Schell’s character; she is vital to the story and Schell’s beautiful playing of the part gives it that little extra something that makes it special. While Frail’s own internal conflict is the main focus, Karl Malden as the lecherous prospector whose unwanted advances bring matters to a head adds another layer. Malden brought out the earthy, feral qualities of Frenchy and his uncouth impulsiveness makes for a fine contrast with Frail’s wounded gentility. In support, Ben Piazza gets a fair bit of screen time and is fair enough as the boy who first resents his savior’s cool arrogance before gradually warming to him and becoming a firm ally. The other parts of note are filled by Karl Swenson and Virginia Gregg as the sympathetic storekeeper and his shrewish wife. Additionally, the ever reliable (and always welcome) John Dierkes flits in and out of proceedings, as does George C Scott, making a showy debut as a venomous preacher/healer.

The Hanging Tree has been available on DVD from a variety of European sources for quite some time now, but always in faded, full-frame transfers. The MOD disc from the Warner Archive improves on these previous iterations in pretty much all areas. The print used is certainly not pristine, displaying the odd scratch and blemish, but it is in the correct widescreen ratio and is much more colorful than anything I’ve seen before. The only extra feature offered on the disc is the theatrical trailer. It’s fascinating to follow how the western grew and built upon its inherent strengths throughout the 1950s, and the end of that decade saw it reach full maturity. The Hanging Tree is certainly a mature work of art, a finely judged and multi-layered examination of human nature and human relationships. For me, these late 50s westerns demonstrate not only what the genre was capable of but what cinema itself had to offer. The more I watch, write and think about the westerns of Delmer Daves, the higher his stock rises. I guess it’s clear enough that I both like and respect The Hanging Tree a lot. I consider it one of my favorites in the genre and I haven’t the least hesitation in strongly recommending it. It’s an absolute must for anyone who appreciates or cares about the western.

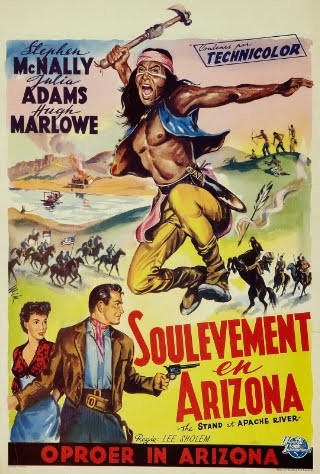

The Stand at Apache River

Something I like to do on this site is feature a mix of the better and lesser known films. When it comes to the latter category there’s no shortage of candidates to be found among the output of Universal studios. Second features or programmers are of course a varied bunch in terms of quality, but it has to be said that Universal, of all the Hollywood studios, had a real knack for producing entertaining westerns on the cheap. These small-scale, unpretentious movies had a polish and tight professionalism to them that’s very attractive. There’s no doubt that these films were constrained by their budgets but that was often turned into an advantage in itself. The Stand at Apache River (1953) is a fair example of a western which both exploits its limitations and simultaneously suffers from them too.

The opening sees a horseman striking out across an expanse of barren country, nervously checking his back trail for signs of pursuit before heading for the rocky high ground and the promise of safety. This man is Greiner (Russell Johnson), a thief and murderer desperate to avoid a date with the hangman. Hot on his heels is Lane Dakota (Stephen McNally), a driven lawman with a personal interest in running down his quarry. When an unexpected skirmish with a couple of Apache leaves Greiner badly wounded, and Dakota without his much needed proof, the sheriff has no option but to seek temporary shelter until the prisoner is well enough to be brought back to face justice. And this brings us to the location where the remainder of the drama will play out – the Apache River ferry station. Dakota’s arrival coincides with that of a stagecoach carrying Valerie Kendrick (Julie Adams) and Colonel Morsby (Hugh Marlowe), the former being an uncertain bride-to-be on her first trip west while the latter is a veteran Indian fighter with a fearsome reputation. No sooner has this little band of travelers gathered at the isolated station than it’s revealed that a group of 50 Apache warriors has broken free from the San Carlos reservation and may be heading their way. This external threat is exacerbated by a number of internal conflicts, among which are Greiner’s eagerness to elude his captor and the friction that arises between Dakota and Morsby over matters of justice and their respective attitudes towards the Apache. When the station finds itself under siege and repeatedly attacked by the Apache all the tensions within are exposed and add to the danger.

While I was watching this movie I found it difficult not to be reminded of Apache Drums for a number of reasons. Firstly, there’s the presence of Stephen McNally in the lead and the fact that the title and credits play over the same footage and images as the earlier film. Additionally, both movies have a similar structure, gradually narrowing in focus and confining themselves to a single set as the story progresses. The Stand at Apache River also tries hard to recapture some of the terrifically claustrophobic atmosphere that characterized and elevated the Lewton/Fregonese film but director Lee Sholem doesn’t quite get there. The lighting and cinematography are similar but the same sense of menace isn’t achieved. Where Lewton and Fregonese kept the Apache largely unseen and thus built them up into frightening bogeyman figures, this movie presents them, or at least their leader, as more rounded characters. While this dissipates the threat somewhat, it does offer the opportunity for some consideration of the nature of the conflict between the settlers and the Apache, deftly highlighting the grievances of and injustices towards the latter group. However, this also feeds into what I see as the main weakness of the movie – essentially there is too much going on. You cannot have drama without conflict but it’s also possible to overdo it. The movie only runs for an hour and a quarter and tries to pack in a siege, commentary on settler/native relations, the problems faced by women in isolated frontier settings, and a love triangle to name just a few. In the end, there are too many themes and too little development – arguably, there’s enough material for a couple of movies here.

Stephen McNally and Julie Adams get the most screen time and both of them turn in perfectly acceptable performances. However, the overstuffed plot which I mentioned does work against them and means that their character development is necessarily limited. This is a shame as both of them have interesting back stories, and the acting chops to take advantage of them, but there’s just not enough time to explore it all further. Hugh Marlowe is fine too as the rigid martinet although his role is fairly one-dimensional. There’s also a nice intense turn by Jaclynne Greene as the frustrated and frightened owner of the river station. Russell Johnson (who passed away just last month) and Hugh O’Brian both play potentially interesting characters, though once again it has to be said they really don’t get the chances to show what they were capable of. The only disappointment for me was Edgar Barrier, who I found pretty unconvincing as the Apache chief.

I guess The Stand at Apache River has to count as a bit of an obscure film these days, and it certainly hasn’t been widely available for home viewing. However, there is a nice DVD out in Spain. Many Universal titles from the 50s seem to be in reasonably good shape and The Stand at Apache River is no exception. The print used isn’t perfect but it’s not at all bad either. While there are a handful of instances of age-related damage, they are few and I wouldn’t refer to them as a particular distraction. Generally, the transfer is smooth, colorful and acceptably sharp. The disc doesn’t offer anything in the way of extras but there’s no problem with subtitles either – there’s the option of French, Spanish or none. All in all, the movie provides plenty of entertainment and excitement. With its short running time it moves along briskly and, leaving aside the matter of the crowded plot, should satisfy those into westerns of this era.

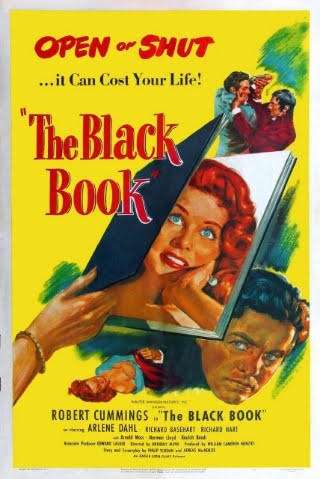

The Black Book

Recently, I’ve been watching a fair bit of film noir, and indeed mulling over and discussing exactly what does or does not constitute noir. And that brings me to a borderline case, a movie that flirts with the notion of film noir, has some of its recognizable characteristics, yet stops short of fully satisfying the criteria. The Black Book (1949) was among the handful of movies Anthony Mann made just before he embarked on his influential and complex cycle of westerns. The film is a historical piece, a mystery/espionage thriller whose visual style is pure noir but whose theme lacks the ambiguity to allow me to comfortably place it in that category.

1794 – France is gripped by revolutionary fervor and the Reign of Terror, presided over by Robespierre (Richard Basehart), is at its zenith. The series of bloody purges have led to an atmosphere of distrust, insecurity and instability. With Robespierre on the verge of absolute power, plans are afoot to overthrow him while there’s still time. But that time is short; within days Robespierre will have maneuvered himself into an unassailable position and the opportunity will have passed. Enter Charles D’Aubigny (Robert Cummings), an agent acting on behalf of the exiled and imprisoned Lafayette. D’Aubigny’s mission is to infiltrate Robespierre’s inner circle, by means of impersonation, and see that the voices of dissent are provided with the means to remove the would-be tyrant before he has them silenced forever. This task is both aided and complicated by two unexpected factors. Firstly, there’s the presence of Madelon (Arlene Dahl), D’Aubigny’s former lover and his principal contact with the anti-Robespierre faction. And then there’s the black book of the title: Robespierre’s death list, a sinister little volume containing the names of those marked down for execution as and when the whim strikes him. It’s this book which forms the basis of Robespierre’s power, it’s impossible to be sure whether one’s name is included and that uncertainty weakens any potential opposition. However, the book has gone missing and the hunt is on to retrieve it before a critical meeting of the ruling Convention. Whoever gains possession of the black book holds the balance of power – able to install Robespierre as absolute dictator or to destroy him completely.

Personally, I feel The Black Book functions well as an allegory for the time it was made. WWII had ended a few short years before and the memory of the terror and slaughter was still fresh in the minds of everyone. It’s no great stretch to see the film as a warning against the dangers of dictatorship; even as the world had witnessed the end of one hateful regime another has risen up to take its place. The purges and sham trials depicted in the film bring to mind the repression and fear of the Stalinist eastern bloc. However, I think too that the critique of the cult of personality and the atmosphere of betrayal and backstabbing can also be viewed as a subtle reminder that even stable democracies can be manipulated by political opportunists under certain circumstances – the paranoia accompanying the red scare of the post-war years was already rearing its head in the US.

Anthony Mann built his reputation on his crime and noir pictures and that influence was carried through to a greater or lesser extent in most of his subsequent films. Thematically, his westerns continued to be psychologically complex even though the visuals (once he began to work in color) moved in a different direction. The Black Book, photographed by John Alton, is much more straightforward when it comes to theme and characterization. The hero is simply heroic; there’s no internal conflict struggling for dominance of the character and no sense that fate has the odds stacked against him. From the viewer’s perspective it’s always very clear who the good guys and the bad guys are, even if some of the motives aren’t quite so apparent. Still, the movie looks like a textbook example of film noir. Mann’s composition and Alton’s lighting create a dark and dangerous world for the characters to inhabit: high overhead shots suggestive of detachment, low angle ones bringing ceilings into focus and emphasizing a cramped, restrictive world, deep and impenetrable shadows slicing menacingly across faces or threatening to consume them totally.

Robert Cummings is generally thought of as a lightweight lead and sometimes dismissed on those grounds. I’ve always liked his crime/mystery roles though – The Chase, Sleep, My Love, Saboteur, Dial M for Murder – and have rarely found him disappointing. If anything, I feel his natural charm lends a touch of vulnerability to his characters. I have no complaints about Cummings’ performance in The Black Book, he handles the tense, suspenseful scenes well and is convincing enough when the need for action arises. Arlene Dahl is good too as the former lover who now has to work closely with the man she once abandoned. A rekindled romance does develop but it never has that tacked on feel that can make such plot devices tiresome. That this aspect works is largely down to Dahl, her coquettish insolence is both refreshing and attractive. Richard Basehart too is very effective as Robespierre; there’s a stillness and calm about him that becomes quite unnerving, only the glittering eyes hinting at the murderous zealot lurking within. As good as the leads are, Arnold Moss steals practically every scene he appears in as Fouché, the oily, Machiavellian politician who’s naked self-interest is a wonder to behold. In support, there are nice turns delivered by Charles McGraw, Beulah Bondi and Norman Lloyd.

For a long time the only way to see The Black Book was via ropey transfers of battered prints. However, Sony put out a MOD disc in the US that seemed to far surpass all previous releases. I never picked up that disc but when Koch in Germany announced their own pressed release of the title I decided to bite. I don’t know if the Koch disc is derived from the same source as the US edition but I can certainly say that I’ve never seen the movie looking better. There are isolated speckles but the print used is in pretty good shape and shows off Alton’s photography to very good effect. Additionally, this disc has the full, uncut version of the movie (as does the US MOD edition) restoring the censored scene that was absent from many of the earlier releases. There are no subtitles offered, just the original English soundtrack and a German dub. Having suffered through some appalling transfers of this film in the past, it’s a real pleasure to be able to see it looking crisp and clean. It may not be proper film noir, but any fan of that style of cinema should get a lot out of this movie – Mann and Alton present some stunning and memorable images. Bearing in mind there’s a satisfying and exciting story here too, I have no hesitation in recommending the film.

Man in the Saddle

The collaboration of actors and directors is a favorite area for analysis by film critics – Ford and Wayne, Mann and Stewart, Huston and Bogart readily spring to mind. That attention tends to get focused on these cinematic partnerships is I think understandable; they offer a reasonably self-contained block of work which can be examined easily. Mention Randolph Scott to western fans and the name that will probably come to their lips is that of Budd Boetticher, again understandable enough given the reputation their series of films together has deservedly earned. However, Scott also made a group of westerns with another director, Andre de Toth, just before he hit his late career peak with Boetticher. Man in the Saddle (1951) was the first, and arguably the best, of a half-dozen movies featuring de Toth and Scott.

The overall framing device is the classic western staple of the range war, the conflict over land and the need for expansion. But that’s actually the least interesting aspect of a story that involves a number of overlapping and obsessive relationships. Owen Merritt (Randolph Scott) is a man under pressure on two fronts; having already lost his woman, Laurie (Joan Leslie), to his powerful neighbor Will Isham (Alexander Knox), he’s now in danger of seeing his ranch go the same way. Isham is one of those typical western expansionists, a man never satisfied with owning half of anything and ruthless enough to use whatever means are necessary to get what he wants. Standing in the path of this irresistible force is the immovable object of Merritt. The only possible outcome of such a paradox is conflict, even though Merritt does his level best to avoid it for as long as possible. What makes this apparently simple tale fascinating though is the way these characters, and those around them, interact. Merritt clearly retains strong feelings for the ambitious and mercenary Laurie, yet he buries them deep, while Isham is fighting an internal duel with his own jealousy and self-doubt. Matters are further complicated by the presence of another neighbor, Nan (Ellen Drew). She quietly pines for Merritt and in turn is herself desired by Clagg (John Russell), a taciturn loner of brooding temperament. When Isham’s hired gunmen up the ante by stampeding Merritt’s herd and killing one of his men all the passions and obsessions of the principals are unleashed. Merritt is forced into taking a stand against his enemies, even those he was hitherto unaware of.

If one views the westerns of de Toth and Scott in relation to the work both director and actor did independently and with others, then it’s possible to undervalue them. But I think such comparisons, even if they’re inevitable, are unfair. Movies really ought to be evaluated on their own terms – do they achieve what they set out to do? Placing them within a wider context does of course serve some purpose but it ultimately does the films a disservice too. What all that’s leading up to is my belief that Man in the Saddle succeeds in telling its tale. Firstly, de Toth’s direction and Charles Lawton’s cinematography combine well and the tension builds nicely. Visually, it’s an interesting movie with a number of scenes taking place at dawn or dusk (perhaps using the half-light to underline the murky, shifting nature of the relationships) and the location work in Lone Pine and Thousand Oaks particularly enhances the latter half. The climax too is notable for the use of a dust storm as an accompaniment to the action and is suggestive of the elemental, swirling emotions of those involved. The only downside of the film, for me at least, was the slightly clumsy way the comedic parts were integrated. Generally, I have no objection to the introduction of a little comedy to lighten the load, but I’m not sure it’s handled all that successfully in this case.

By the end of his career Randolph Scott had almost elevated the depiction of the stoic acceptance of loss and regret to an art form in itself. One of the more rewarding things about watching those films leading up this is the ability to observe how that persona gradually evolved over the years. As Merritt, Scott touches on this idea of losing the woman he loved. That loss isn’t as fully defined or as final as would be the case in the later movies with Boetticher, but it’s there all the same. Alexander Knox isn’t an actor normally associated with westerns, making only three throughout his career, yet he’s fine as Scott’s rival. He’s very convincing as an emotionally repressed man and this is even more effective when he actually lets loose all his pent-up rage. In truth, all the main players acquit themselves very well: Joan Leslie as the hard-edged pragmatist, Ellen Drew as the calm Girl Friday, and John Russell as the outsider twisted by his unrequited passion. My only complaint is that Richard Rober is underused as the smiling gunman.

Man in the Saddle is readily available on DVD and has been for many years. The US disc from Sony/Columbia presents the film nicely in its correct Academy ratio. This older transfer comes from a good print and boasts strong, vibrant color with plenty of detail. The disc doesn’t have much in the way of extra features, just a standard preview reel for other Sony/Columbia movies available. However, the movie is the main thing and the presentation here should give no cause for complaint. The westerns that Randolph Scott made with de Toth have been overshadowed to a large extent by the later Ranown cycle, yet they’re enjoyable in their own right. Aside from allowing viewers to fill in some gaps in tracing the development of the Scott persona, these movies are good examples of the professionalism to be found in the Hollywood western of the 50s. Man in the Saddle may not be the best thing Scott or Andre de Toth ever did but it’s still a pretty good film and is worthy of the talents of all involved.

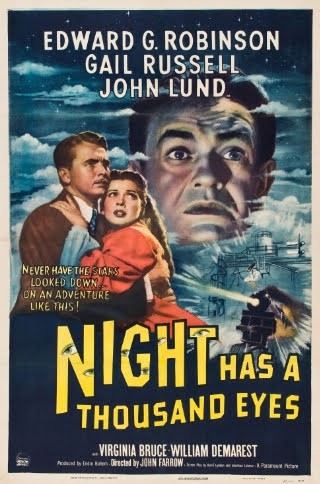

Night Has a Thousand Eyes

I’d become a sort of a reverse zombie. I was living in a world already dead, and I alone knowing it.

Film noir is at heart a fatalistic genre. Greed, stupidity, desire and deceit all play a significant part to be sure, but back of it all is the implication that human beings are locked on a predetermined path which circumstance or fate has chosen for them. Whether or not one subscribes to such a theory is neither here nor there; it’s enough to know that it underpins much of film noir. But what if we already knew what lay in store? Would it be possible to cheat fate and regain control of our lives? That’s the basic premise of Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948), a noir with a quasi-supernatural slant.

The film opens dramatically with Jean Courtland (Gail Russell) about to take her own life by throwing herself in front of a train. The suicide bid is thwarted at the last moment by Elliott Carson (John Lund), her fiance. But why would a beautiful young woman such as this want to end it all? The answer to this is provided by John Triton (Edward G Robinson), once a small-time mind reader and now a virtual recluse, a prisoner of his own unique talent. Via a series of flashbacks Triton reveals his connection to Jean and the odd events that have shaped his life. Depending on one’s point of view, Triton has either been blessed or cursed with the ability to foretell the future. As his weary narration points out, there were initial advantages to this, such as the knack of predicting how best to make money. Despite these indisputable benefits, Triton gradually came to see that prior knowledge of various tragedies had a corrosive effect on the soul. Slowly, the feeling began to eat away at him that he might be in some way responsible for some of the things that happen. His first reaction was to ignore the premonitions in the hope that doing so might avert them. When that doesn’t work he settles on an alternative course of action; he will actively try to prevent the outcomes that periodically flash before his eyes. And it’s this which leads him into the life of Jean Courtland. Jean is the daughter of his late fiancée, a woman he left and let marry his best friend. That sacrifice failed to save the life of his former love, but a vision of Jean’s imminent death routs him out of self-imposed exile. For twenty years Triton has hidden himself away from the world, shunning human contact. Now however, he decides to take on fate directly. It’s a duel of sorts between a desperate man and the mysterious force that seems to determine all our futures. The prize at stake: the life of a young woman, and the chance for Triton to shake off the unwelcome curse bestowed upon him.

John Farrow is a director I’ve always had a lot of time for. He was extremely versatile, working in a variety of genres and turning out a handful of highly entertaining and well crafted noir pictures. Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a brisk piece of work, yet there’s also a dreamy, melancholic feel to it. The first half is taken up with the flashbacks that explain how Triton’s gift mutated into a curse, and Robinson’s voice-over adds to the noir atmosphere. The latter section sees the focus narrow and is largely confined to Jean’s home, as the police, various retainers and Triton all gather to see if the predictions come true. The fusion of noir motifs and supernatural overtones is unusual and quite successful in my view. While film noir was grounded in at least a superficial reality, there was also an element of the fantastic running through it. I guess the fact this movie was based on a Cornell Woolrich novel, given that writer’s penchant for outrageous and sometimes bizarre plot twists, accounts for this mix. Another point of interest is the sympathetic or tolerant stance adopted towards the whole issue of spiritualism. Generally, film and literature of the 30s and 40s tended to be downright hostile when it came to examining the spiritualist craze that grew out of the aftermath of WWI. Most books and movies focused on debunking the techniques of the fake mediums and phony spiritualists, exposing them for the charlatans they were.

While Farrow’s direction is solid and Woolrich’s material is always interesting, it’s the performance of Edward G Robinson that really powers the film. By his own admission, Robinson possessed an air of menace that was often used to great effect. Yet, in reality, Robinson was a highly cultured man and could impart great sensitivity when he was afforded the opportunity. The role of Triton was such an opportunity, a tortured soul robbed of the love of his life and endowed with a terrible gift. Robinson had wonderfully expressive features and it’s a real joy to see him tuck into a meaty and complex part like this. Although he’s the unquestioned star of the movie, he gets good support from John Lund and Gail Russell. Lund’s role is a bit of a thankless one as the stoical, skeptical romantic lead, but he does all that’s required of him. Russell had that tragic, ethereal beauty that works so well on screen and there’s a vague air of confusion about her, a sense of one lost in the world. Somehow, her magical presence seems entirely appropriate in such a film.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a movie that’s just crying out for a decent DVD release. The film can be viewed online quite easily and there’s a DVD available from Italy but neither option shows the movie in the best light. I have that Italian disc and it has to be said the print used is pretty beat up. It’s taken from an Italian source, the titles and credits are presented in that language, and it’s a dirty, scratchy affair. Despite the poor condition and lack of restoration it does remain perfectly watchable throughout. The disc offers the choice of either the original English soundtrack (no subtitles) or an Italian dub. The theatrical trailer and a text essay (in Italian) comprise the extra features. This was originally a Paramount production so, given the lack of any word of Olive releasing it, I’m guessing the rights now reside with Universal. I can only hope that it gets a stronger release somewhere in the future – it deserves it. Regardless of any complaints about the current presentation and availability of the movie, it remains an intriguing film noir. A neglected little gem, ripe for rediscovery.

EDIT: Laura also wrote a piece on the movie here, which I only just noticed.