I just found out that the site has been accepted as a new member of the Large Association of Movie Blogs. Excellent – the listing is here.

I just found out that the site has been accepted as a new member of the Large Association of Movie Blogs. Excellent – the listing is here.

Sounds like a contradiction in terms, doesn’t it? There are those who have deep reservations about applying the noir label to any film not shot in black and white. Personally, I don’t share that feeling but I can understand where those who hold the view are coming from. In purely visual terms, film noir inhabits a landscape of shadows and high contrast photography. Effects such as those are much more difficult to achieve when shooting on color stock, although it’s certainly not impossible.

Of course this also raises the question of whether or not one ought to define film noir in visual terms alone. I don’t see how such a narrow definition can be applied to so amorphous a style of filmmaking. For me, film noir must have an essential darkness, a bleak view of humanity and human relations, at its heart. I guess the point I’m leading into here is that there are a good many movies that utilize classic noir imagery and visuals yet couldn’t, by virtue of their theme, be considered true film noir. The 1940s in particular boast an abundance of movies, especially although not exclusively crime thrillers, which look like typical examples of film noir, but clearly they are not. As such, is the reverse not also true? Can’t a movie be shot in vibrant color but still contain that dark core that is unmistakably noir?

Wikipedia offers a list of movies which it claims are films noir shot in color:

While I haven’t viewed every one of these, I have seen the majority. I suppose I would have a few quibbles but I reckon the list is a reasonable one overall. How do others feel about this? Would you exclude the above titles on the basis of their being shot in color? Or, neo-noir excepted, should that list be expanded?

That man is a creature of hell. If he stays here, he’ll turn this town into a hell.

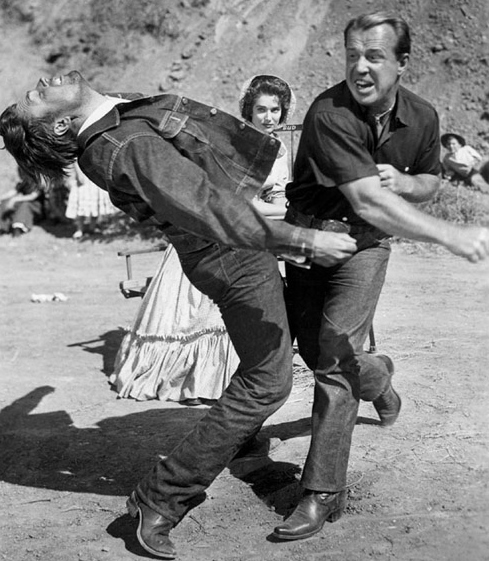

Quite a few westerns have served as social commentaries, using their frontier setting to focus the spotlight on a whole range of issues, as frequently acting as an allegory for the era in which they were made as much as a critique of the old west itself. A Day of Fury (1956) is an interesting case in that it’s less of a social commentary than an examination of human nature, and the less savory side of it at that. I think part of the beauty of the adult-oriented westerns of the 50s lies in the way programmers with modest budgets could tackle complex themes successfully while also telling entertaining stories. It sometimes feels like current filmmakers have lost this once commonplace skill, either overtly preaching at the audience or veering sharply in the opposite direction and rolling out mindless popcorn fare where you’re required to check your brain at the door. As such, it’s genuinely refreshing to watch a movie like this where the makers have sufficient respect for their audience to present an entertaining film while simultaneously crediting them with a modicum of intelligence.

A Day of Fury opens by telling the audience that the Civil War has ended, the frontier is closing, and civilization is advancing. As such, the implication is that we’re in for another end of the trail western, another look at the passing of a way of life. Well that’s true enough up to a point, and yet A Day of Fury is good deal more than that. It’s neither an ode to lost innocence nor a celebration of a brighter future ahead. Instead the movie operates on a more spiritual level, holding up a mirror to the human soul and daring us to take a long hard look at what may be lurking within. Everything starts off in a fairly straightforward manner with a lone horseman, Jagade (Dale Robertson), stumbling into an ambush being set up. The proposed victim is Burnett (Jock Mahoney), the local marshal. When Jagade saves the lawman’s skin it looks like a lead in that’s been seen on many occasions. However, there is also a sense that this film is going to head off in a different direction, the terse dialogue between Jagade and Burnett hinting at something darker and less predictable. Jagade rides ahead into town, ostensibly to tell Burnett’s bride-to-be (Mara Corday) that her man has been delayed, but his real motives gradually become apparent. If there was a tension or edge to the initial meeting between Jagade and Burnett, it’s ramped up considerably as soon as the former sets foot in town. Jagade is a gunfighter, a lethal killer whose reputation precedes him. In fact everything about Jagade harks back to a rapidly disappearing era: from his own violent skills to his acquaintance with the marshal’s betrothed and her time as a saloon entertainer. For Jagade, this represents a last stand of sorts; the changing world around him has left him with no other place to go and he seems keen to turn the clock back. Still, that only amounts to a superficial interpretation of the film. We all know that the past is nothing more than a memory which, despite the strongest yearning, can never be recaptured. And so it is with Jagade; his true function is to confront the facade of respectability and gentility that the town has constructed. The pious righteousness is simply a veneer, and one so thin that it starts to crumble when the slightest pressure is applied. Jagade could, I suppose, be viewed as a kind of malignancy that will have to be cut out at some point, but he could reasonably be seen as the cure as much as the illness. Over the course of one Sunday, and there is significance to the fact that the Sabbath is chosen, the townsfolk begin to regress and descend into the type of amoral thuggishness they had frowned upon only a few hours before. And that’s what I feel the movie is all about – the question of whether our civilized values are so cheap they can be bought or traded away, or whether the roots are deeper and stronger.

Aside from the first five minutes, director Harmon Jones keeps the action of A Day of Fury confined to the backlot western town. While I’m in no doubt budgetary considerations played a big part in that decision, I think it works well on an artistic level too. Everything is contained within a series of tightly controlled locations, heightening the tension and dread that grows as the story progresses. Recently, Toby published a fascinating article in which he revealed that Dale Robertson viewed his character in the movie as an incarnation of the Devil. As I said earlier, the film does have a definite spiritual element running through it and Robertson’s reading of the role is in line with that. Personally, the notion of the movie as a religious allegory makes sense and works: the initial meeting in the desert-like surroundings between Burnett and the left-handed Jagade, and the subsequent temptations that are variously succumbed to, resisted, and overcome. If I had any criticism of this approach, it would only be that I think the final shot of the film arguably lays the symbolism on a little too heavy, and that the message had already been successfully imparted without it. To return to the point I made in my introduction, besides all the ideas and food for thought offered up, the filmmakers never lose sight of the primary goal of presenting an entertaining and well-told tale.

A Day of Fury boasts a strong cast of western players. Dale Robertson’s Jagade is clearly the center of attention, the catalyst for all that takes place. And it’s a marvelously ambiguous part, a character who provokes and toys with those around him. The fact that it all works so well is partly down to the scripting of course, but Robertson’s skill cannot be discounted. There’s an air of authority about the man, a calm self-confidence, tinged too with a touch of distaste both for himself and the weakness all around him. In the opposite corner is Jock Mahoney, stoic, reserved and cool. One could say there’s a passivity to Mahoney’s playing here, but it’s a vital aspect of his character – the only serious rival to Robertson’s satanic influence and the solid rock to whom the town must ultimately turn. And lying somewhere between these two is John Dehner as the preacher. Always a welcome face as far as I’m concerned, Dehner represents the most easily identifiable figure in the town, a man who’s not above weakness but who is also able to recognize that fact and actively work to resist it. As for the others, Mara Corday has a showy part as the former saloon girl whose past returns to haunt her and threaten her future happiness. I thought her weary acceptance of the fragility of so-called respectability was very well realized. In support, Jan Merlin had a pivotal role as the fawning, rat-faced acolyte whose actions finally cause the tide to turn while Carl Benton Reid, James Bell and Howard Wendell all turn in small but noteworthy performances.

A Day of Fury isn’t that difficult to see these days. There’s a Blu-ray available from France, although I’m unsure what the subtitle situation is seeing as it’s a Sidonis release. As a result, I ended up buying the Italian DVD. This may well come from the same source as the image is of excellent quality: the movie is presented in a 2.00:1 anamorphic transfer and comes from a print that exhibits little or no damage. The disc offers the movie either with the original English soundtrack or an Italian dub, subtitles are optional and can be deselected via the setup menu. Extra features consist of the trailer along with poster and photo galleries. The film itself is one I was eager to see as I had heard a lot of things about it from people whose opinions I greatly respect. I was delighted to discover it was every bit as good as I’d been led to believe. I’ve always enjoyed focusing some attention on pictures that are not so well-known, and I guess this one fits that description. I reckon this is a terrific little movie and should provide plenty to appeal to genre fans and those who simply like smart, well-made films.

Just a quick post here to acknowledge the fact that this place will have been open for business for six years tomorrow. Sadly, as I’m sure regular visitors have noticed, my output of late has slowed down considerably. Frankly, I’ve been hard pressed to find the time to post due to some pretty heavy work commitments. I think readers here have come to expect a certain level of quality and I don’t wish to knock out sub-standard material just to satisfy some notional quota. Suffice to say I’ll be posting when I find the time to write something which I feel has some worth. Anyway, I didn’t want the anniversary to slip by without thanking all those whose visits and contributions are the life blood of this site. More articles and the like will follow guys, just not quite as often as before.

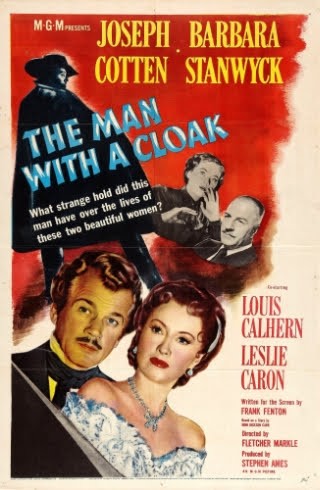

Lots of different things draw us to movies. Personally, I’ve always been a fan of Gothic mysteries, particularly those where the Hollywood majors cooked up that special atmosphere that could only exist within the carefully crafted confines of a studio set. Add in a rare adaptation of the writings of John Dickson Carr and I’m hooked. The Man with a Cloak (1951) combines both of these elements, and it was a film that had intrigued and eluded me for years. It’s been quite some time since I read Carr’s short story The Gentleman from Paris, but I remember enjoying it and was keen to see how the film version worked.

It’s 1848 in New York, the year that saw revolutions breaking out in so many parts of the world. Against this turbulent backdrop a young woman arrives in the US seeking help. She is Madeline Minot (Leslie Caron), a somewhat unlikely fundraiser for a political cause. Her mission is to seek out the assistance of her fiance’s uncle, Charles Thevenet (Louis Calhern), now living in dissipated and debauched exile in the wake of Napoleon’s downfall. Madeline had been expecting to be introduced to a distinguished gentleman, instead she finds a half-crippled drunkard seeing out his days in decaying splendor. Thevenet’s alcohol sodden existence is being overseen by a trio of servants and retainers under the supervision of Lorna Bounty (Barbara Stanwyck). Two things are clear right away: Madeline’s presence is unwelcome in this household, and Thevenet’s protectors are no more than vultures patiently circling their dying master. And so it all comes down to money, Thevenet’s got it and everybody else wants it. While Madeline cannot prove that Lorna and her cohorts are actively plotting to murder the old man, she knows that it’s clearly in their best interests to see that he doesn’t hang around long enough to make any changes to his will. Into this little circle of greed and deceit steps Dupin (Joseph Cotten), the mysterious poet of the title who spends his days cadging free drinks from a sympathetic barkeep. Dupin isn’t motivated by the promise of money, though he’s clearly badly in need of it, rather he’s drawn to the simple faith in life of Madeline and a desire to see an injustice averted. It’s Dupin’s arrival that forces Lorna’s hand and brings the two mysteries of the film center stage: the puzzle of Thevenet’s will, and the real identity of the enigmatic poet.

The Man with a Cloak was directed by Fletcher Markle, a man who is probably better known for his television work. There are some highly effective scenes and a handful of noteworthy visual flourishes, and yet I can’t help feeling that the potential of the story and its setting weren’t fully exploited. The film has that polished look that MGM typically brought to its productions, and the studio sets are faultless. Still, the tension is allowed to slacken too often and that’s partly down to the failure to make the most of the visual opportunities. As for the plot, it’s solid enough but it’s perhaps overly dependent on building up an aura of mystery around the character of Dupin. While it’s adapted from a reasonably entertaining Carr story, it’s not one that highlights the author’s real strengths. In short, there’s arguably too much emphasis on who Dupin actually is – the film is liberally sprinkled with clues and it shouldn’t prove all that difficult to work out for any fairly literate viewer.

While the direction and scripting of the movie are always competent, they are nothing exceptional either. What does give the film a boost though is the acting. Both Stanwyck and Cotten were seasoned professionals, capable of tackling a variety of roles. Cotten spends most of his time hovering around the borders of sobriety, and gets to deliver some witty and telling lines. His character displays a weary cynicism, a sort of metaphorical cloak for the unnamed sadness he carries within himself. Against this is ranged the steely pragmatism of Stanwyck. Her outer gentility and polish masks a barely repressed sensuality and a deep streak of bitterness – after all, we’re talking about a woman who feels she has been robbed of ten of the best years of her life. While Cotten and Stanwyck rarely put a foot wrong, Louis Calhern almost effortlessly steals just about every scene. I sometimes think that if you want to capture a visual representation of regret for a life of unfulfilled promise, then you need only watch one of Calhern’s performances from around this time. In the face of such stiff competition, Leslie Caron fades into the background most of the time. It’s not that her portrayal of a frightened and confused ingenue is especially poor, just that she lacks the presence to make her mark among these heavy hitters. It’s a rare film that doesn’t benefit from a strong supporting cast, and The Man with a Cloak is no exception. Margaret Wycherly looks like she had a ball as a cackling old crone, and Jim Backus is a delight as the Irish bartender trading philosophical jibes with Cotten.

The Man with a Cloak was until recently another of those films that I began to think I was fated never to see. However, it became available via the Warner Archive, and shortly afterwards was given a pressed disc release in Spain via Llamentol. I watched the Spanish disc the other day and, judging from some screen captures I’ve seen, it looks like a clone of the US disc. Generally, the transfer looks pretty clean and sharpness and contrast are quite acceptable. This release offers no extra features whatsoever, just the film with its original soundtrack and the option to watch it with or without Spanish subtitles. I’ve seen people allude to the film’s noir credentials before but I feel the link is tenuous at best, and it’s not a title I’d be comfortable labeling in this way. For me, The Man with a Cloak is simply a Gothic mystery with a generous dollop of melodrama added. Overall, I found this an enjoyable and entertaining movie, though it’s not without its faults. I guess the presence of some big name stars and the fact it was sourced from a John Dickson Carr tale raised my expectations perhaps a tad too high. Nevertheless, I couldn’t say I was especially disappointed. If the direction is a little flat at times, the performances do compensate. Anyone who enjoys these studio bound mysteries, likes Carr’s writing, or is a fan of Stanwyck and Cotten should find enough to satisfy them here.

Those seeking another take on the film should pop over to Paul’s place at Lasso the Movies.

Well, I’ve given myself another tough task here. Having tried something similar with actors before, I thought I’d have a go at the men behind the cameras. Once again, the sheer number of westerns produced, especially during the classic era, means that almost every director of note made a few. As such, picking my top ten represents something of a challenge. I decided to stick as far as possible with specialists, those whose names tend to be closely associated with westerns, or those who made a significant contribution to the genre, either stylistically, thematically, or through their work with particular stars. The first half-dozen or so are easy, more or less picking themselves. The problems start to become apparent further down the list though, resulting in a bit of soulsearching on my part to determine who would and wouldn’t make the cut. Anyway, for what it’s worth, here’s my selection.

John Ford

Clearly, the man who identified himself as a maker of westerns has to occupy top spot. It’s truly impossible to overstate the importance and influence of the extraordinarily complex old Irishman. So much of the imagery popularly associated with the genre stems directly from Ford’s films. From myth maker to myth buster, Ford dominated the development of western filmmaking like no one else before or since.

Anthony Mann

Starting out in film noir, Antony Mann brought some of that dark ambiguity to the western. His series of movies throughout the 1950s demonstrated how the genre was the ideal vehicle for the examination of tortured and flawed personalities. If Ford placed his characters in an iconic landscape, Mann went a step further and merged that landscape with the characters themselves.

Budd Boetticher

Boetticher’s reputation has grown over the years, to the point where the Ranown cycle with Randolph Scott must be regarded as an essential component of the canon. Those beautifully crafted films fold into one another, their lean directness providing a masterclass on how to produce high art on a budget. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Boetticher was making these mature little gems at the point when the western was just reaching its peak.

Sam Peckinpah

More than anyone else, Peckinpah exemplifies the western’s transition from the classic to the modern era. Tales of his battles with the studio bosses and his own inner demons are legion, but the result was a handful of masterpieces of cinema. Maybe we didn’t always get to see exactly what Peckinpah had originally intended, and the emphasis on his depiction of violence tends to cloud the appreciation of the man’s artistry. However, he kept the western moving forward and pushed it in new directions at a time when it was threatened by stagnation.

Sergio Leone

While I remain ambivalent about the spaghetti western in general, my respect and admiration for Leone is unshakeable. He tends to be popularly characterized as the man who brought about a sea change in the way the genre developed, a new broom if you like. I’ve argued before that I don’t believe that’s entirely true – he was steeped in the mythology of the western and owed a huge debt to Ford, paying unashamed homage to the old man in his greatest works. If you take the time to look, there’s clear evidence that the western was already starting to move towards the place that Leone ultimately took it. Nevertheless, he did reinvigorate the western and his influence on filmmaking continues to be felt.

Clint Eastwood

A recent post of mine led to a long and fruitful discussion of Eastwood’s contribution to the genre. A variety of opinions ended up being expressed but the one thing everybody seemed to agree on was the fact that the western would be a lot poorer without Eastwood. Personally, I feel he’s owed a huge debt of gratitude for almost single-handedly keeping the genre I love the most alive during its leanest years.

Raoul Walsh

The man who gave John Wayne his first big break, and according to some stories even gave him his name, returned to the western again and again throughout his career. Walsh tends to be regarded primarily as an action specialist, and there’s no doubting his flair for that aspect of the job. However, he also understood the importance of strong characterization and knew how to fully exploit the potential of his actors – he managed to draw the best out of Errol Flynn for example.

John Sturges

The best directors seem to have a knack for hitting their stride at the just the right time. John Sturges was an unquestioned master of widescreen composition and took full advantage of that skill just as the process was becoming established. I guess Sturges’ best known western is still The Magnificent Seven, and that’s nothing to be ashamed of. Personally, I tend to prefer his smaller, tighter efforts from the 50s – even if he’d only ever made Last Train from Gun Hill, he’d still be on this list.

Robert Aldrich

I mentioned the spaghetti western earlier, alluding to the fact that such developments don’t just spontaneously appear. Hollywood could be said to have first glanced furtively in that direction in 1954 when Aldrich made Vera Cruz, but the genre wasn’t yet at a point where a leap into fully fledged amorality was either desirable or possible. Still and all, it can be argued that Aldrich had laid the groundwork.

Delmer Daves

My final pick is a man whose work has risen progressively in my estimation over the years. I’ve come to deeply appreciate what I regard as the essential optimism that permeates his westerns of the 50s. His finest films contain moments of understated intimacy that are enormously powerful and unashamedly poetic.

So there you have it. I doubt if anyone would seriously argue with the inclusion of the first six names on my list. As for the others, I’m sure they won’t meet with everyone’s approval. There are strong cases to be made for directors like Hathaway, de Toth, Wellman, Tourneur, Ray and Hawks. Ultimately though, I had to whittle it down to ten and it was inevitable they couldn’t all make the cut. Feel free to drop in and add your own thoughts.

To me the most important thing to know about an assassination is not who fired the shot – but who paid for the bullet.

The passage of time can have a nasty tendency to cloud the memory, to cast a kind of nostalgic haze over things and distort reality. On occasion I’ve found this to be the case with films, where fondly remembered movies, those which have earned themselves a special place in the heart over the years, fail to live up to their promise. It’s quite a crushing disappointment to discover that a film we thought was wonderful long ago falls far short of the stellar image we’ve built up in our imagination. Happily though, that’s not always the case, and sometimes it just happens that the film we saw all those years ago really is the little gem we’ve been yearning to see again ever since. The Mask of Dimitrios (1944) is one such movie; I caught it once on a late night TV broadcast at some point during my teenage years and it made a big impression on me. However, it never seemed to show up again no matter how carefully I scoured the TV listing pages in the papers. It also remained stubbornly absent from DVD release schedules to the point I began to despair of ever seeing it again. In the interim I’d read the Eric Ambler novel from which it had been adapted, and that actually just served to increase my frustration. Anyway, when I finally learned of its DVD release this year I experienced a rush of excitement tinged with a hint of trepidation. Fortunately, the latter feeling turned out to be misplaced as I realized my memory hadn’t been cheating me. Ah, the ups and downs of being a movie fan!

It’s 1938 and the uncertainty and upheaval of the inter-war years will soon be swept aside by the approaching conflict. In Istanbul a group of children run happily along the shores of the Bosphorus. They halt abruptly, shocked by the gruesome sight before them. The body of a murdered man has washed up and now lies carelessly on the sand. The clothing and papers identify the remains as belonging to one Dimitrios Makropoulos, a Greek national and a man not unfamiliar to the authorities. Later that evening, at a party, the Turkish security officer in charge of the investigation falls into conversation with Cornelius Leyden (Peter Lorre), a mystery writer vacationing in the Levant. The tale of the shady character now lying on a mortuary slab intrigues Leyden and piques his writer’s interest. Armed with only a handful of dates and locations, Leyden takes it upon himself to satisfy his curiosity and make a stab at tracing the movements of this notorious figure. Leyden therefore sets out on a journey that will take him first to Athens, then on to Sofia, Belgrade, Geneva and finally Paris. Along the way, via a series of flashbacks narrated by an assortment of middle European types, he begins to piece together a picture of the mysterious and ruthless Dimitrios (Zachary Scott). At every turn though, Leyden’s path seems to cross that of Mr Peters (Sydney Greenstreet), a man whose interest in Dimitrios surpasses that of the diminutive writer. It soon becomes apparent that the threat posed by men such as Dimitrios doesn’t end with death, and that his malignant influence may even extend beyond the grave.

The Mask of Dimitrios is one of those pictures that sails awfully close to the boundaries of film noir; the fates of Dimitrios’ victims certainly moves it in that direction as does the shadowy photography and multiple flashbacks employed. However, despite the presence of these persuasive factors, it’s the mystery/espionage elements that dominate for the most part. The story comes from Eric Ambler’s finest novel (high praise indeed as the man rarely wrote anything weak) and I reckon the film stands as the best adaptation of his work to date. Generally, Ambler’s stories dealt with men who found themselves drawn unwittingly into the murky world of spying and underground politics. By having the bulk of the action play out in the Balkans, that hotbed of intrigue and shifting loyalties, The Mask of Dimitrios captures the mood of betrayal for profit beautifully. Both Ambler’s writing and Jean Negulesco’s atmospheric direction leave the viewer in no doubt that we’re being taken on a tour of a world of secrets, memories and confidences cherished for emotional and material value. For me there are two standout sequences in the movie. The first is the framing story in a cheap night club in Sofia. Faye Emerson is wonderfully weary and faded as she recounts her past with Dimitrios: the air is thick with a kind of smoky decadence, Emerson’s near lifeless eyes and drawn expression speak volumes, and the band plays Perfidia in the background. The other noteworthy episode is an extended flashback to an elaborate sting in Belgrade, where a minor government official has his own weakness manipulated in order to suck him into committing treason. The combination of Dimitrios’ cold slickness and Steven Geray’s portrayal of the poor dupe whose fragile ego, thwarted ambition and desperate desire to rise in his wife’s estimation makes it quite affecting.

Of the half-dozen or so movies that Greenstreet and Lorre made together in the 40s, The Mask of Dimitrios was the one that gave them the greatest opportunity to shine. Something like The Maltese Falcon handed them fascinating roles, but they were still only there to provide support for Bogart and Astor. This film, on the other hand, places the two men front and center and it’s their partnership as much as anything that carries the whole thing. As Peters, Greenstreet has the more ambiguous part, and gets to indulge in his patented trick of switching from jovial bonhomie to dark menace in the blink of an eye. Lorre acts as the viewer’s guide, half leading and half stumbling his way through the twisting tale. Zachary Scott is of course the true villain of the piece, and the movie offered him one of his best parts. He always had an oily charm that could be used to strong effect when necessary, but this time that quality remains largely buried beneath a cold, calculating facade. As the story progresses the full extent of Dimitrios’ foul character is gradually revealed, and Scott manages to convey very successfully just how dangerous this man truly is.

As I said at the beginning of this short piece, The Mask of Dimitrios was a difficult film to see for a long time. Earlier this year though, it appeared on DVD via the Warner Archives. At the time I felt ambivalent about this fact; I wanted to get my hands on the film but I’ve never managed to completely overcome my aversion to buying DVD-R products. When I learned over the summer that Absolute in Spain were putting out their own pressed disc version of the movie, I decided that was the one I’d go for. Absolute can generally be relied on to produce solid, attractive releases, and this is no exception. The image doesn’t display any noticeable damage and has nice contrast levels to show off the noirish photography. As usual with this company, subtitles are no issue and can be deselected from the setup menu. Extra features consist of the theatrical trailer and a booklet (in Spanish naturally) containing notes on the film and a good selection of stills. OK, so I had been a little fearful that the film wouldn’t prove as entertaining as I hoped, but it ended up being every bit as satisfying as I recalled. Personally, I think it’s a terrific example of the magic that studio bound B thrillers could conjure up when the right cast and crew were handed promising material. Do yourselves a favor folks and check this one out – it comes highly recommended.

It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. Take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have. – Unforgiven (1992)

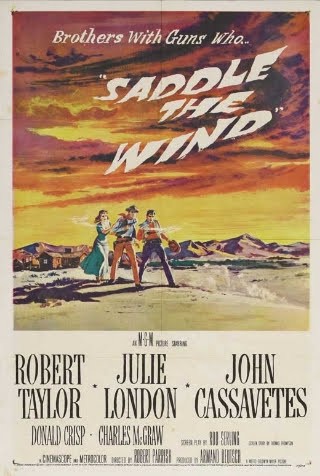

I decided to open with the above quote to prove a point of sorts. It’s a point about perception, the way cinema tricks us into believing certain things, or at least the way those who write about cinema shape our views. There are plenty of people who point to Eastwood’s Unforgiven and hold it up as the ultimate myth buster. I like the movie well enough but it does bring a wry smile to my face when I hear it lauded as a film which highlighted the corrosive effects of violence on men who lived by the gun. It’s easy to see how those unfamiliar with the genre, or even those with only limited exposure to it, could buy into the theory that Unforgiven is a bigger game changer than it really is. There is a tendency among some, probably fueled by the influence of the spaghetti western, to imagine the genre was all about cool, trigger-happy gunslingers prior to 1992. Somehow, the perception arose that the western shied away from or glossed over the consequences of violence and killing. Yet if one goes back to the golden decade of the 50s, it’s clear that the genre had already faced such themes head on. Saddle the Wind (1958) is a film about killing, a painful and probing examination of the repercussions of pulling a trigger and taking a life.

The opening sees a stranger (Charles McGraw) riding into town. He’s one of those bristly, hard-bitten types, the kind of guy who oozes insolence and aggression, who demands rather than asks. Men like this have a swaggering confidence born of the knowledge that they’re tough, mean and fast enough to carry it all off. Anyway, he makes it clear that he’s looking for a man, Steve Sinclair (Robert Taylor), and guys such as this don’t come looking for men just to be sociable. Steve Sinclair is now a respected rancher but he has a murky past that he’s trying to live down, having once been a famed gunman and killer. So what’s new, you may ask. Thus far the scenario is one that ought to be familiar to anyone who’s seen more than a handful of westerns. Well Steve is a man who has learned from the sins of his youth, he’s become a reformed character and has rejected violence. However, Steve has a younger brother, Tony (John Cassavetes), who appears to have inherited the worst traits of his elder sibling. Tony is more than just a cocksure kid with a gun and a point to prove; he’s a damaged human being, a walking stick of dynamite without a hint of remorse and a lust for killing. We first see Tony as he arrives home with a girl he intends to wed, former saloon singer Joan (Julie London), and a new gun. It’s immediately clear that there’s something itching away under Tony’s hide: he deposits his betrothed in the house, introduces her to all, and then proceeds to indulge his real passion. Where a normal guy would fawn and fuss over his newly acquired fiancée, Tony instead gets straight to work honing his shooting skills with his new six-shooter. Not only that, but there’s a manic, obsessive edge to his practice, rounded off by his blasting away at his own reflection in the water – which of course foreshadows the film’s climax. And this, more than anything else, is what the whole movie is really about, two very different brothers and their attitude to violence. The more Steve tries to rein in the excesses of his brother, the more Tony strains against that moderating influence. What finally brings the conflict to a head is the arrival of a former Yankee soldier (Royal Dano) bent on claiming his family’s legacy and stringing the dreaded barbed wire on the open range. Tony’s overreaction and stubborn refusal to heed Steve’s call for calm leads to a tragic confrontation. His neglect of Joan has already irritated Steve, but it’s his determination to usurp the authority of the local land baron (Donald Crisp) which finally forces the two brothers into a situation where only one can walk away.

Robert Parrish isn’t a director whose name will be familiar to many these days. However, he made a string of fine films throughout the 50s, culminating in the truly excellent The Wonderful Country. I recall reading somewhere that Parrish was unhappy that he wasn’t given full control over the final cut of that movie; I don’t know if that’s true but the fact remains his career as a director appears to have slumped dramatically after hitting that peak. Anyway, Saddle the Wind (with its screenplay by Rod Serling of The Twilight Zone fame) comes awfully close to being his best work – I reckon The Wonderful Country just about pips it to the post but there’s not a lot in it – with some memorable visuals and an extraordinarily powerful theme. Pitting brother against brother always makes for good drama. When you mix in the simmering resentment left over from the Civil War, and a scathing critique of machismo and the culture of violence then it all adds up to something quite special. It’s that last point which I mentioned in my introduction, and I’d like to explore it a little further here.

Others have pointed out that the scene where Jack Palance gunned down Elisha Cook Jr in Shane was a pivotal moment in the development of the western, and I’m not going to argue with that. That proved that gun play and violence was a mean, dirty business. Saddle the Wind follows on from that and literally hammers the point home: apart from the heartfelt speeches delivered by Taylor and Crisp at various times, the killings that take place in the film, and there aren’t actually that many, are grim and brutal. No-one dies easily; as the bullets tear into bodies, the victims clearly suffer, twitching, kicking and coughing to the bitter end. And then there’s the aftermath, the consequences of taking a life. Two of the characters (Crisp & Taylor) bear the psychological scars of a violent past and their world view is shaped by that. For me, it’s this mature consideration of the effects of violence on the souls of men that marks Saddle the Wind out as one of the great westerns of the greatest decade of the genre.

The more often I watch Robert Taylor’s westerns, particularly those of the late 50s, the more I come to view him as one of the most significant figures in the genre. I didn’t include him in my list of the top ten western stars which I compiled at the tail end of last year, and I tend to think now that it may have been a major omission. I guess Taylor is never likely to attain the status of Stewart, Scott or Wayne but his finest western roles made a big contribution to the genre. In Saddle the Wind he achieved a marvelously quiet dignity, a kind of pained courage that projected all-round masculinity as opposed to juvenile machismo. Taylor’s calm awareness of his own strengths and weaknesses contrasts well with the strutting bravado of Cassavetes. Now there’s a figure one wouldn’t normally associate with the west. Cassavetes had a very urban and modern air about him, a guy who it’s hard to imagine outside of a big city environment. Yet that otherness, that discomfort with his surroundings, works under the circumstances. Cassavetes’ character is a young man at war with himself, and by extension with the whole world around him. If Cassavetes doesn’t truly belong in this frontier setting then it’s merely a reflection of the character whose psychological flaws and displaced morality set him apart from those around him. He honestly comes across as some unbridled force of nature, and Taylor’s futile efforts to tame him could easily be seen as a fruitless attempt at saddling the wind. These two men unquestionably dominate the film but it’s also important to mention the work done by Donald Crisp and Royal Dano. Crisp was always good in patriarchal roles and his benign presence in this movie is every bit as touching and influential as the rather different yet comparable part he played in Anthony Mann’s The Man from Laramie. Royal Dano was one of those character actors who seemed to pop up all over the place, and his halting delivery and hunted look tend to stick in the mind. Saddle the Wind offered him a role to get his teeth into, a desperate man driven on by his private sense of honor and justice. And that brings me to Julie London. Her fame today derives from her singing (and she provides a beautiful version of the theme song of this film) but she also starred in three exceptional westerns around this time: The Wonderful Country, Man of the West and the film under discussion.

Saddle the Wind was an MGM production and so it was released on DVD by Warner Brothers a few years ago in their Western Classics box set. The film has been given a very good transfer to DVD, the anamorphic scope image looking bright, clean and colorful. The location photography in Colorado looks quite stunning in places and the audio is also strong with the gunshots packing a considerable punch, and Elmer Bernstein’s brooding score sounding rich. The only extra feature offered on the disc is the theatrical trailer. I believe this is a very fine western, although nowhere near as well-known as it deserves to be. I see it as further proof of how far the western had progressed by the late 50s. However, the fact that thoughtful films like this are only infrequently mentioned can also be regarded as evidence of the regression the genre experienced through the following decade. Anyway, next time someone claims that a film such as Unforgiven broke entirely new ground in terms of its critique of violent lifestyles, you can simply point them towards this production and tell them it’s not as new a concept as they first imagined.

The conflict in Ireland has provided the backdrop for a number of quality movies over the years, and I’ve covered a few of them on this site: Odd Man Out & The Gentle Gunman. Those two films dealt mainly with the smaller mid-century campaigns in Northern Ireland or around the border. Shake Hands with the Devil (1959) steps a little further back to the early 20s and the War of Independence, concentrating on the south of the country. The “Tan War”, so named after the involvement of the British irregulars recruited to strengthen the RIC, remains an emotive subject in Ireland due to the atrocities perpetrated against the civilian population. I can clearly remember people of my grandparents’ generation, who lived through those turbulent and violent times, speaking with undisguised venom about the Tans. The film under examination here reflects that hostility, but doesn’t shy away from depicting the implacable fanaticism that characterized some elements within the Irish rebel movement at that time either.

The prologue makes it clear that the Ireland of 1921 was a country in a state of war. The opening then takes place in a Dublin cemetery where a solemn funeral procession makes its way along paths lined with tombstones. Suddenly, a squad of Black and Tans appear and the cortege scatters amid the jarring sound of gunfire, leaving behind an upturned coffin spilling its load of rifles. This brief scene succinctly illustrates the nature of the war being fought: a covert organization facing off against a determined and ruthless enemy. The most interesting films dealing with the Irish conflict feature those caught somewhere in the middle, dragged into the fighting in spite of themselves. Kerry O’Shea (Don Murray) is such a man, an Irish-American studying medicine in Dublin in fulfillment of his late mother’s wishes. O’Shea happens to be visiting his parents’ grave when the Tans’ raid takes place, and he will find himself drawn deeper into the war as the story progresses. O’Shea’s father had been an old-time republican and he had fought in WWI himself; as such, we see a young man who has had his fill of killing. Still, circumstances don’t always allow a man to follow the path he would prefer – sometimes just being in the wrong place at the wrong time alters the course of a life. This is what occurs with O’Shea; he is walking along a street when an IRA ambush leads to the shooting of his friend and the subsequent leaving behind of his notebook at the scene during his flight from the violence. A direct consequence of this is the revelation that O’Shea’s lecturer and eminent surgeon Sean Lenihan (James Cagney) is a commandant in the IRA. As O’Shea, now regarded as a suspected terrorist, goes on the run, the combination of the brutality of the Black and Tans and the fact that Lenihan once saved his father convinces the young student that his place is standing shoulder to shoulder with the rebels. Yet despite O’Shea’s belief in the essential nobility of his cause, he becomes increasingly disturbed by the harsh, fanatical side of Lenihan. This feeling of unease is further strengthened when Lenihan’s customary dislike for and distrust of women is magnified after the taking of an important hostage; Jennifer Curtis (Dana Wynter), the daughter of a high British official, is abducted in reprisal for the imprisonment of an elderly republican sympathizer. Lenihan’s near pathological hatred of the young woman, and his keenness to see her executed, may prove the ultimate test of O’Shea’s loyalty.

Politically, Shake Hands with the Devil wears its heart on its sleeve, and makes no bones about its critical appraisal of the role of the Black and Tans in Ireland. The Tans are explicitly cast as the villains of the piece, their commander being portrayed as a quasi-fascist figure with a strong sadistic streak. The way O’Shea’s interrogation and beating is photographed, in a highly subjective manner, emphasizes the cold brutality of his tormentor. However, if there is a sustained effort to romanticize the rebels – most notable in the characterizations of Cyril Cusack, Michael Redgrave and Sybil Thorndike – it needs to be pointed out that we’re not looking at a whitewash job either. The internal discipline mechanisms of the IRA are shown in all their toughness, and the unyielding aspect of what would become the anti-Treaty forces – as represented by Cagney – is one of the major themes of the film.

Michael Anderson was a director capable of great visual flair – I’ve commented in the past on the Hitchcock-style touches present in a couple of his films – and Shake Hands with the Devil offers further evidence of his eye for interesting compositions. Aside from having a knack for capturing the correct mood, he staged and shot the action sequences very fluidly. The early part of the movie was shot on location in a mean and moody Dublin, all expressionistic shadows and dripping in noir atmosphere. Later, the action moves out of the city to Bray and the coast, and again Anderson, aided by cameraman Erwin Hillier, makes the most of the windswept seaboard. The use of the lighthouse, where the rebels have set up a makeshift headquarters, gives a nice claustrophobic feel to the scenes where Dana Wynter is held captive. Generally, the authentic locations contribute to the sense of realism and, while the script does meander a little in the middle, Anderson’s assured and inventive direction holds the attention throughout.

What can one say about James Cagney? From gangster to song and dance man, and just about everything in between, he was and remains one of the greatest Hollywood stars ever. Shake Hands with the Devil was one of his last films before entering a retirement that he refused to be persuaded out of for over twenty years. The film saw him surrounded by top class performers and expert scene stealers, yet it’s Cagney who carries it and he’s the one who sticks in your mind. The tough little New York Irish pug had been strutting and swaggering across the screen for thirty years by that time and his presence was such that it positively demanded you sit up and pay attention. He was always an actor capable of great intensity, although there was always a liberal sprinkling of charm and humor just below the surface too, and he honed and perfected that quality over the years. The part of Sean Lenihan gave Cagney a chance to flex his not inconsiderable acting muscles; it’s a complex role where the character alternates between a sympathetic, gutsy figure and a dangerous obsessive with deep and dark personal issues.

Cagney was certainly the name at the top of the bill, but there was a long list of talented and big name performers filling the other roles. Michael Redgrave was credited simply as The General, a character who seems to have been based on the real life Michael Collins. Aside from a moment of ruthlessness, Redgrave imbues this man with a sense of dignity, nobility, and just the appropriate touch of tragedy. There’s also an excellent turn from Cyril Cusack as the poet turned revolutionary who befriends the lead; it’s a thoughtful performance and a pivotal one, anchoring the film and acting as a bridge between the driven Cagney and the more reluctant Murray. Frankly, Don Murray was handed something of a thankless task when he had to square off against such a battery of talent. Having said that, Murray is good enough and, while he hadn’t the same depth of experience as some of his co-stars, acquits himself very well indeed. Richard Harris would of course go on to great things and his part as one of the more thuggish and self-absorbed rebels was an early opportunity to show what he was capable of. As for the women, Glynis Johns and Dana Wynter have the meatiest parts. Johns was the loose and brassy barmaid while Wynter was the demure and well-bred gentlewoman. Both actresses were convincing and quite touching in these contrasting roles, coaxing the best and worst from the male characters. As has already been stated, the supporting players in this movie makes for impressive reading: Sybil Thorndike, Niall MacGinnis, Harry H Corbett, William Hartnell, Ray McAnally, John Le Mesurier, Allan Cuthbertson and Noel Purcell.

Shake Hands with the Devil is available on DVD in the UK via Metrodome. The film is presented in Academy ratio, which can’t be right for a 1959 production. I did try zooming to around 1.66:1 at a number of points and the image generally looked fine so I guess we’re looking at an open matte transfer here. Leaving aside the matter of the aspect ratio, the transfer isn’t bad in other respects – print damage is minimal and contrast levels and sharpness all look acceptable. The only extra features on the disc are a handful of trailers for other Metrodome releases. Regular visitors to this site will be aware that I try to highlight movies that aren’t always widely acclaimed. Naturally, some are of better quality than others and I feel comfortable in asserting that Shake Hands with the Devil really is something of a forgotten gem. It’s an interesting film from a historical perspective, focusing on a conflict and period that doesn’t get a lot of attention. Michael Anderson’s smooth direction is very attractive with the imagery frequently reminiscent of film noir. Add in some excellent acting and complex characterization, especially from Cagney, and we’re talking about a first-rate thriller.

The western is a genre which, although it’s certainly not the only one, is sometimes accused of being overburdened by clichés. This is understandable enough; genre pictures by definition have to feature elements that are immediately recognizable to viewers. Canyon Passage (1946) could be said to contain its fair share of these well-worn tropes (crooked financiers, restless wandering types, hostile natives) but part of what raises this film up among the best examples of the genre is the way they are handled. There’s an air of authenticity about it all, and that filters through into some stock characters and situations, bestowing on them an originality that sets the whole production apart.

While I don’t have any statistics at hand to prove this one way or the other, I reckon it’s safe to say most westerns take place within a rough thirty year period beginning at the outbreak of the Civil War. Sure you’ll get examples set both before and after these dates, but they do appear to be slightly thinner on the ground. Canyon Passage tells a tale of Oregon in 1856, a time of growth and expansion before conflict engulfed the nation. Logan Stuart (Dana Andrews) is one of those thrusting, entrepreneurial types, never satisfied with what he has and always on the lookout for new opportunities to add to his fortune. Still, he’s not a greedy or grasping man; his ambition is just an integral part of his character, a restless need to range further and in some ways a reflection of the pioneering spirit of his country. Stuart is a man who is going places in every sense: his business is booming, he’s respected within the community and he’s courting Caroline Marsh (Patricia Roc), a beautiful English settler. However, there’s almost always a fly in the ointment, two in this case. The biggest and ugliest comes in the shape of the brutish Honey Bragg (Ward Bond), a muscle-bound giant of a man and an amoral counterpoint to Stuart. A further source of anxiety is George Camrose (Brian Donlevy), the local banker and Stuart’s best friend. Camrose is a compulsive gambler, a dangerous trait in a financier in any circumstances but doubly worrying when he’s caught in a run of spectacularly bad luck. While Camrose attempts a precarious balancing act his fiancée, Lucy Overmire (Susan Hayward), is increasingly attracted to Stuart. Granted none of this is making his life any easier, but it pales into relative insignificance in comparison to the physical threat represented by Bragg. The hulking bully is borderline obsessive in his rivalry with Stuart, further enraged and embittered by his knowledge that his foe had (and passed up) the opportunity to see him hang. Fueled by hate and frustration, Bragg gives in to his animal instincts and thus imperils not only Stuart but the whole community when his base behavior sparks off a tragic Indian uprising.

Adapted from a novel by prolific western author Ernest Haycox (Stagecoach, Union Pacific, Bugles in the Afternoon, Man in the Saddle etc) Canyon Passage was the first foray into the genre for director Jacques Tourneur. The versatile Frenchman took to westerns right from the beginning, crafting an intimate portrait of frontier society that comes close to the affectionate and mythic vision of John Ford. Cameraman Edward Cronjager captured some truly beautiful and breathtaking Technicolor images that Tourneur then directed with an expert touch. The sequence of the cabin raising is an ode to communal effort and gives a real sense of how inextricably linked the lives of these people were to those of their neighbours. Everything in the movie – the texture of the buildings, the condition of the streets, the language and attitudes of the characters – smacks of a realism that isn’t always present. However, the movie is more than a celebration of pioneering spirit and the social dynamic of the time. Above all, Tourneur was a master of atmosphere and an extraordinarily subtle, understated director. There is plenty of rousing action accompanying the narrative, and again the authentic feel comes across in the depiction of the violence. No doubt Tourneur’s experience working in Val Lewton’s horror unit at RKO shaped his approach to filming the more horrific scenes. There is very little explicit violence shown on screen, the director preferring to cut away or obscure the more visceral moments. Yet the effect, as was the case in those Lewton movies, is to force the viewer’s imagination to take over. In my opinion anyway, having to visualize the acts just off screen is more unsettling than seeing some unconvincing mock-up.

With strong source material and first class people operating behind the cameras, the final vital ingredient is the performers. Dana Andrews produced another of those deceptively quiet turns as Logan Stuart. Initially, you’d be forgiven for thinking this man was no more than a hard-nosed and pragmatic businessman. However, as the story progresses, Andrews, as he so often did, reveals new layers to the character. His early scenes with Patricia Roc hint at a tenderness of heart not apparent from his stoic visage, and this aspect is further developed as his relationship with Hayward grows. But really it’s his loyalty to Donlevy that proves how deep his humanity runs. Although Donlevy was of course a great heavy in countless movies, I wouldn’t actually class his George Camrose as a fully fledged villain. Despite some thoroughly reprehensible behavior, Donlevy brought a weakness and frailty to the role, a touch of corrupt romanticism if you like, which helps explain why Andrews stuck by him all the way. No, the real bad guy here comes courtesy of Ward Bond’s portrayal of the monstrous Honey Bragg. Bond did a fantastic job in capturing the physical power, the depravity and animal cunning of this figure. The two main female roles – those of Patricia Roc and Susan Hayward – are careful studies of contrasting women. Roc had the right kind of brittle gentility for an Englishwoman suddenly thrust into a new and dangerous world; her dazed and distant reaction to the aftermath of the Indian massacres struck just the right tone. Hayward, on the other hand, was feisty, tough and earthy – a true frontier gal. In supporting roles, there is some good work from Lloyd Bridges, Andy Devine, Onslow Stevens, and the wonderful Hoagy Carmichael.

Canyon Passage is a Universal film, and there are plenty of DVD editions on the market from a variety of territories. I have the version included in Universal’s Classic Western Round-Up Vol. 1 which was released a number of years ago. The film shares disc space with The Texas Rangers but I can’t say I was aware that the presentation suffered from any compression issues. For the most part, the image is very strong with the Technicolor cinematography looking frankly spectacular at times. There are no extra features whatsoever available on the disc, something I think is disappointing as the movie is most certainly deserving of a commentary track at the very least. Regardless of that, this movie remains among one of the very best westerns made in the 1940s. Jacques Tourneur would go on to make a number of high quality pictures in the genre, though I feel this represents him right at the top of his game. There’s a complexity and maturity to the characters and their interactions that help distinguish the movie. Not only would I recommend Canyon Passage to anyone with an interest in westerns, I would go so far as to say it’s essential viewing.