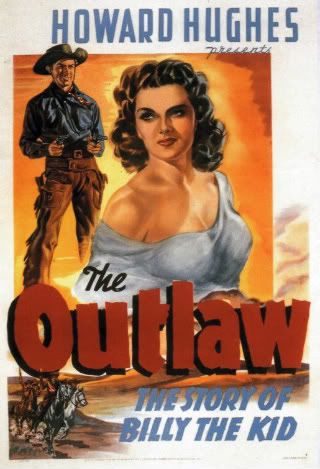

It’s hard to know where to begin with a film like The Outlaw (1943), or indeed what to make of it at all. It takes the characters of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett and dumps them into a story that bears no relation to reality and frequently defies logic too. Ultimately, it’s a showcase for the fantasies and obsessions of Howard Hughes (two very prominent ones in particular) and its failure as a motion picture can be traced back to that. There are some astonishingly bad aspects to this film but, almost perversely, there are also times when it looks like it might just turn the corner and become something worthwhile. However, it never manages to tear itself free of Hughes’ grip, and every time an opportunity to go somewhere interesting arises it misses its step and simply lapses back into parody.

Within minutes of the opening the viewer is shown the meeting of Billy (Jack Buetel), Pat Garrett (Thomas Mitchell) and…Doc Holliday (Walter Huston). Yes, that’s right – Doc Holliday. So right from the off all semblance of reality is swept away and it’s clear that what follows is going to strain credibility to the absolute limit. Anyway, it transpires that Billy stands accused of stealing Doc’s horse – whether or not he did is never really resolved and the saga of the disputed ownership recurs time after tiresome time throughout the movie. Just when it looks like these two noted gunslingers are going to shoot it out the party is broken up by the intervention of Doc’s long time buddy Garrett. The result is that Doc finds himself ruefully admiring the Kid’s pluck and subsequently taking his side, much to the disappointment of Garrett. This switch of allegiances is regarded not only as a breach of friendship but also as a kind of humiliation by Garrett. When a saloon killing forces him to place Billy under arrest, Garrett is once again wrong-footed by Doc and their enmity is sealed. With Billy wounded and the law in hot pursuit, Doc leaves the Kid in the care of his girl Rio (Jane Russell) while he heads for the hills and safety. Now Rio and the Kid had met before, in a dark stable where they wrestled around some. However, the Kid is now laid low by his wound and the resulting fever, so he’s in no condition to continue where he left off. This lengthy sequence in Doc’s cabin, as Rio nurses the Kid back to health and falls for him in the process, is supposed to define the central relationships of the film. The fact is though it kills the narrative stone dead and contains not only some truly awful shots but also has the misfortune of being dominated by two performers making very obvious debuts. The only good thing to be said is that it contains an imaginative method employed by Rio to break a dangerous fever – I’ll have to see if it works the next time I’m running a temperature. After this tedious interlude the story attempts to regain some momentum with Garrett finally catching up with his quarry, only to be blindsided again. There is some dramatic tension to be had from seeing Garrett’s disillusionment spiralling off into murderous frustration, but as soon as this happens Hughes manages to drain all the pathos away and negate what should have been a powerful moment. And that sort of sums up the whole production.

The Outlaw is of course remembered for the furore it caused with the censors and the Hays Office. Were it not for Howard Hughes’ fascination with Jane Russell’s ample form, and the battle he undertook to have his picture exhibited, this movie would likely have faded into obscurity. Hughes’ shooting style, seen at its worst and most self-indulgent in the interminable cabin sequence mentioned above, is an object lesson in bad filmmaking. The zooms, cuts and fades employed are jarring and meaningless exercises, like a schoolboy playing with a new toy. The action scenes that punctuate the story do have some merit though and are worthy of attention. I also think it’s fair to say that the shots in the movie that retain some style and character are likely the result of having the great Gregg Toland behind the camera. As for the acting, Buetel and Russell are clearly making their first picture – Russell fares better, and her subsequent career can be seen as proof that she did have ability. Buetel, on the other hand, is very weak and it’s almost cruel to see his lack of range exposed by the presence of two classy old veterans like Walter Huston and Thomas Mitchell. If one wanted to be generous it could be argued that Buetel managed to convey the sense of awkwardness and innocence of a young man forced to grow up too soon. Both Huston and Mitchell really anchor the film and prevent it spinning off course completely; when one or other is on screen there’s always a feeling of reassurance, and the only real criticism is that they’re far too old to play the characters they’re supposed to be. The big dramatic scene that forms the climax, where Doc shoots pieces from the Kid’s ears to provoke him into drawing, gives Huston a chance to impose himself as Mitchell sits slyly in the wings. Mitchell, of course, gets his big moment too when he follows up by pouring out his pent up frustration and shredded pride. This should have seen things end on a high note but Hughes’ botches it again with an ending that’s ridiculous and insulting in equal measure. Thus far I’ve pointed out many of the shortcomings of this movie, but there’s one more that needs to be mentioned. The score. Music plays an integral part in film; it can enhance a mood and complement a scene, it can even lend a whole new dimension to a sequence. But, used poorly, it can also draw the life from a picture and sap the tension. What I can only describe as “comedy cues” pepper the action in The Outlaw at the most inappropriate moments and actively damage a number of key scenes.

The Outlaw has long been a staple of the PD market and there are countless editions of it floating around on DVD. For the purposes of this piece I viewed the Legend Films version that came out about two years ago. Legend, of course, are known for their penchant for colouring in old B&W movies; however, they also do a clean up of the print beforehand and offer both versions. The B&W print is probably as good as I’ve seen the film looking, although it’s certainly not perfect either. There’s a softness about the image at times, especially evident in the longer shots, and some instances of minor damage. This release was a two disc set: the first disc offering both the restored B&W and the colourised versions, and the second comprising only the colourised one with a commentary by Jane Russell and Terry Moore. Frankly, I have no intention of ever watching the crayoned in version so I’ve yet to hear the commentary – I’ll probably give it a listen some time in the background when I don’t have to endure the garish visuals. Anyway, I think it ought to be clear that I’m not a fan of this particular movie. In its defence I will admit that Walter Huston and Thomas Mitchell give good performances and there are a few well staged action scenes. But the acting of the young leads, Buetel especially, leaves a lot to be desired. That and Hughes’ mediocre direction combined with some ill-conceived scoring really drag the film down. It’s the kind of picture that perhaps deserves to be seen for its poorness alone. Basically, though, it’s a half baked turkey that’s not worth going out of one’s way to catch.

There haven’t been too many westerns that are set around Christmas, in fact I’m struggling to think of any others apart from 3 Godfathers (1948) and the earlier versions of the same story. While it starts out as a fairly standard western it soon turns into a play on the nativity story and the journey of the three wise men. It’s one of John Ford’s more sentimental pieces and the symbolism is laid on a little thick at times, but the cast and visuals carry it through the sticky patches. I’ll grant that the whole thing can seem a bit contrived yet the story, and its message of redemption and the good that lurks within all of us, remains affecting.

There haven’t been too many westerns that are set around Christmas, in fact I’m struggling to think of any others apart from 3 Godfathers (1948) and the earlier versions of the same story. While it starts out as a fairly standard western it soon turns into a play on the nativity story and the journey of the three wise men. It’s one of John Ford’s more sentimental pieces and the symbolism is laid on a little thick at times, but the cast and visuals carry it through the sticky patches. I’ll grant that the whole thing can seem a bit contrived yet the story, and its message of redemption and the good that lurks within all of us, remains affecting.