You know, the more westerns I watch, and discuss with others, the more convinced I’ve become that the smaller, less ambitious productions actually offer a better representation of the strengths and weaknesses of the genre. The leaner budgets mean that the writing, shooting and performances are more honed, less indulgent, and therefore maybe a little more honest and direct. Hell Bent for Leather (1960) is what is known as a programmer; the B western had disappeared and been absorbed by television, but there was still a place for those movies which weren’t going to open as headline A features. The movie is a fine example of economy filmmaking; it demonstrates the benefits of a simple yet tight plot, a small and experienced cast, and a director capable of making the most of his locations.

The story is a very simple one, a case of mistaken identity leading to a desperate manhunt. At the risk of overselling it, Hell Bent for Leather tells a kind of Kafkaesque tale of senseless persecution, the reasoning behind it all only gradually becoming apparent as the narrative unfolds. It opens starkly, with a lone figure staggering out of the wilderness, clutching a shotgun. It’s clear the man is dehydrated and nearing exhaustion, but salvation is at hand – he spies a horseman who has just stopped to eat and rest. This is Clay Santell (Audie Murphy), a horse dealer travelling on business. No sooner has Santell extended the hand of hospitality to the bedraggled figure who’s stumbled upon his camp than that gesture backfires spectacularly. Finding himself viciously clubbed to the ground and his mount stolen in payment for his kindness, Santell only has time to loose off a single shot, winging his assailant and causing him to drop his distinctive shotgun. Santell is now in a similar fix to the man he foolishly tried to help, forced to make his way on foot to the nearest settlement. After this shock beginning, the plot slowly takes on a surreal, nightmarish quality. That shotgun Santell picked up has a history; it belonged to a notorious outlaw who’s been terrorizing the area, in fact most of the townsfolk are at that moment burying his latest victims. However, descriptions of the wanted man are vague, vague enough to fit a lot of men, someone like Santell for instance. There does remain one hope though, the marshal who’s been on the killer’s trail and knows him by sight. Incredibly though, when this lawman, Deckett (Stephen McNally), turns up, he immediately identifies Santell as his quarry. In the face of such a predicament, Santell takes the only option open to him: he makes a break for it with a local girl, Janet (Felicia Farr), as hostage and heads for the hills. What remains to be seen is whether Santell can stay one step ahead of the relentless posse, convince anyone of his innocence and, crucially, discover what motive lies behind Deckett’s seemingly inexplicable actions.

It’s difficult to watch any western from this period that is shot in and around Lone Pine, featuring a limited central cast and a minimalist plot, and not be reminded of Budd Boetticher. I wouldn’t go so far as to suggest Hell Bent for Leather measures up to the quality of Boetticher at his best (there are issues with the script, which I’ll come back to, preventing such comparisons) but it certainly treads a nearby path. The film was presided over by George Sherman, one of those journeymen directors whose work, in spite of a long and varied career, tends to be glossed over if not wholly neglected. However, a look at his credits for the late 40s and on through into the 50s reveals a number of quality genre pieces. Sherman shot the bulk of this film outdoors on location, and made the most of Lone Pine’s distinctive rock formations. These serve both as the backdrop and also the main stage upon which the drama is played out. Whether the camera was positioned at ground level, the viewers’ gaze straining upwards to pick out the tiny figures scrambling over the sun-baked surface, or high above and aimed down through the narrow gaps with cold objectivity, the primal, treacherous nature of the terrain is always apparent. Also, for a movie that involves comparatively little gunplay, Sherman maintains the sense of danger and menace, both through the expert handling of his locations and by ensuring that the pace is never allowed to flag.

As I mentioned, the biggest problem with this film comes from the writing, or at least one aspect of it. When you look at a Boetticher movie, especially those written by Burt Kennedy, you’re immediately struck by the quality of the characterization. Those films all provide the leads with plausible and relatively full backstories. Now, Hell Bent for Leather is essentially a three-hander, revolving around Santell, Janet and Deckett. The details concerning the latter two are filled in as the story goes along, quite deftly too, but Santell’s background is not. By the end of the movie, we don’t know any more about this man than we did in the opening minutes. As a result, the lead, the man with whom we must sympathize, is left as a kind of cipher, a guy to whom bad things happen just because – very existentialist but not entirely satisfactory.

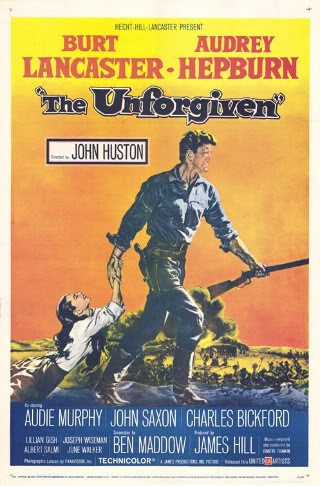

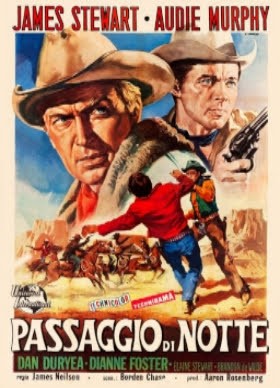

Given the lack of assistance from the script, it says a lot for Audie Murphy’s abilities that he was able to make the part of Clay Santell work. Murphy rarely gets much credit for his acting, but he could turn in a decent enough performance when the film was of some quality. Even though his part is provided with virtually no background, he still makes Santell a man worth rooting for in Hell Bent for Leather. Being cast in what’s essentially the role of the underdog naturally helps to garner sympathy but he also managed to keep the character real, remaining convincing as he moved from bemusement and disbelief through panic and determination.

Felicia Farr had already shown she could handle the role of a western heroine with some accomplishment in a series of films with Delmer Daves, and continued that trend here. Her character is fleshed out as the movie progresses, and she does come across as a woman with an inner strength that keeps her going in the face of adversity. The best, or most interesting, part in the movie was handed to Stephen McNally, an actor who was always a strong supporting player. He really gets under the skin of the driven, slightly unhinged Deckett. At first, this might appear to be a fairly one-dimensional character, but he develops further towards the end. By the time we reach the climax, there’s been enough revealed about Deckett to explain his actions and even create a touch of pathos.

At the moment, Hell Bent for Leather is available on DVD in three countries: Spain, France and Germany. The German release comes via Koch Media, and it’s another of their strong efforts. The film is presented in anamorphic scope, with good levels of detail and rich colour. As for extras, there’s the theatrical trailer, a gallery and booklet of liner notes in German. The disc offers both the original English soundtrack and a German dub, there are no subtitles at all. It’s also worth mentioning that Pegasus in the UK are rumoured to have this movie lined up for release so, bearing in mind the high quality transfers of Universal titles they have recently put out and their competitive prices, it may be worth holding off on this one for a bit. I feel this film is a superior little programmer that’s well acted and directed, and looks very attractive. It’s one of Audie Murphy’s most enjoyable pictures and also highlights the directorial skills of the underrated George Sherman. All in all, this is a solid, nicely crafted western that represents the genre well and shows what can be achieved with a limited budget and a bit of imagination.