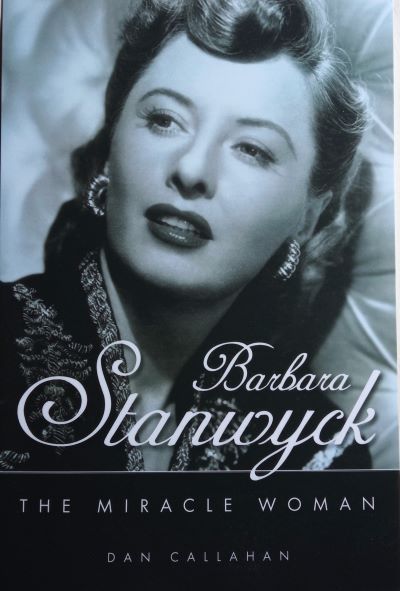

There was a time when writing on the cinema was a bit thin on the ground. Then movie writing, criticism, and frankly anything related to the screen seemed to explode. Genres were hashed, rehashed and dissected, sometimes in celebration and sometimes in condemnation, theories were propounded and expounded, and reputations were analyzed, constructed and dismantled. That issue of reputations was and indeed is most noticeable in the writing of biographies. The movie biography, with its focus on those who have lived out their lives under the typically remorseless and unforgiving glare of publicity can prove problematic. Let’s face it, everyone writing a book wants people to read it and in the field of movie biographies the temptation to angle for readers using the promise of juicy personal revelations as bait must be a powerful one. Personally, I’m not all that interested in how well or badly individuals behaved in their personal lives – it is the public persona, or the screen work to be more accurate, which would have drawn my attention in the first place. As such, I often approach biographies with caution – too much gossip and too little appraisal of someone’s body of work doesn’t really appeal to this reader. Happily Dan Callahan’s book on Barbara Stanwyck, first published in hardback in 2011 and recently reissued in paperback by the University Press of Mississippi, does not go down that route , although there are some other issues present.

The book is not a standard bio, it’s an examination of the person via their screen, and to a lesser extent, their stage work. Callahan divides his study into seventeen chapters, each focusing on a different aspect of Stanwyck’s career. While it’s not a strictly chronological journey the chapters themselves do look at her performances and projects in that way. It begins with a short look at the star’s beginnings in life itself and her first steps as a performer. Callahan devotes separate chapters to the films she made for Frank Capra, Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder, Douglas Sirk, to her appearances in films noir, in westerns and in screwball comedies. There is also an in depth look at what the author sees as one of her defining roles in King Vidor’s Stella Dallas. This is an approach which I think makes sense as it attempts to unravel common threads running through movies that, either as a result of the genre or the filmmakers involved, tend to have a shared sensibility. All the major films receive attention and Callahan offers his own take on their strengths and weaknesses.

In terms of structure and organization, the book is very appealing. Added to that is the fluid style of writing, one which is largely engaging and never overburdened with jargon or the kind of impenetrable formality that tends to afflict more academic texts. These are all positive aspects. However, as was mentioned above, there are other points which I have a few reservations about. I think the easiest way to express this is to note that the book is the work of someone who is clearly a fan of the actress. People may be wondering why that’s used as a lead-in to some of the book’s weaknesses, so let me expand a little. I feel the author is a fan of the actress above all, to the extent where he is frequently dismissive, or at least ungenerous with regard to some of the films she appeared in and the people she collaborated with. Frank Capra and Peter Godfrey both come in for some strong criticism, the former for his approach or vision, and the latter for his filmmaking in general. Those are just a couple of examples, but the writer regularly praises the quality of Stanwyck’s work, occasionally drawing inferences from events in her personal life and how they may have affected her screen work. In itself, that’s fine, but, more often than I feel is necessary, I detect a strong tendency to denigrate films and some other performers and artists in order to highlight his subject’s talents. The films that are slated and those which earn praise seem to be selected on a puzzling basis too. I was pleased to see only one chapter dedicated to her personal life, and at least some effort made to tie that into her career development as well. Stanwyck’s first husband Frank Fay comes off quite badly; it has to be said I’ve never heard anyone have a good word to say about the man so that’s hardly surprising. I did find it odd though to see the author take such a virulent dislike to Robert Taylor, both as an actor and as a person.

So, I found Callahan’s book a bit of a mixed bag. It is informative and offers some detailed analysis of Stanwyck’s movies, is organized and presented in a satisfying way, comes with a complete filmography and an index, but I would have preferred if he could have reined in or disciplined his fandom and enthusiasm and allowed more fairness in certain assessments.

Barbara Stanwyck – The Miracle Woman by Dan Callahan

252 pages. Paperback edition published 2023 by University Press of Mississippi