“When your number’s up, why fight it, right? And if it’s not, why worry about it?”

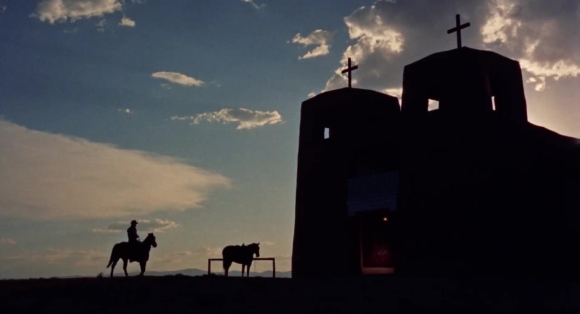

Fate and faith. That line quoted above is delivered with a kind of petrifying calm by Rod Taylor’s flyer during one of the many times he and his maker passed within a hair’s breadth of one another in Fate Is the Hunter (1964). He is by his words and by his actions a fatalist, believing that most of what happens in life, the larger scale concepts at any rate, are beyond one’s control. It’s part of his attraction, lending a devil may care aspect to him that draws people when it’s carried off with aplomb. And then there is faith, such an important and defining principle in the human condition. One may or may not subscribe to the former, but the latter (and not necessarily in a religious sense) surely touches all of us and influences our approach to life. Both of these ideas are explored in Ralph Nelson’s movie, where the trappings of the genre picture – in this case the aviation thriller/disaster movie – are used to frame a fairly simple tale of one man’s belief in the character of his friend and, consequently, in his own judgement.

There is a lengthy prologue, the routine preparations for a transnational flight filling up most of the time and introducing three main characters – pilot Jack Savage (Rod Taylor), his friend airline executive Sam McBane (Glenn Ford), and stewardess Martha Webster (Susanne Pleshette). So yes, all fairly routine, until it’s not. A fault in an engine, then a communications glitch, and then the other engine fails. And then the crash. Of those on board only the stewardess survives and it falls to McBane to sift through the little evidence available in order to fix the cause of the disaster. The airline seems keen to put pilot error on the part of Savage forward as the reason, and the air of raffish irresponsibility he spent his life cultivating backs up this approach. However, McBane is unconvinced, partly due to a sense of self preservation as his championing of Savage over the years has left his own acuity at least on the periphery of suspicion, but perhaps more importantly he balks at the notion his friend was so careless as to be the one solely responsible. In his efforts to see beyond the easy way out, he finds himself delving into the past, the past of Savage to be exact, trying to clear the man and in a way trying to clear his own conscience, to validate his faith in a friend and in himself.

Anyone going into this movie with the expectation of seeing a thriller of some kind is likely to be disappointed. There is the tense build up to the crash in the prologue, and a pretty suspenseful reconstruction undertaken right at the end, but that’s about it in terms of standard thrills. The rest of the movie, the bulk of the narrative, is a character study, an examination of who Savage was and why he acted as he did, largely told by means of multiple flashbacks, each one colored somewhat by the sensibilities of the person doing the telling but also by the spirit of the man himself. By the end, we have gained a broader perspective on this ebullient fatalist, the views of those touched most deeply by their contact with him having reshaped this both subtly and decidedly. The net result is that the truth is arrived at by a combination of chance and logic that is apt under the circumstances, and on a deeper level McBane feels vindicated not only since he has salvaged the reputation of his friend but because in so doing he has reaffirmed the primacy of faith.

Ralph Nelson had a spotty, patchy kind of career, veering wildly from genre to genre and hard to pin down stylistically. Fate Is the Hunter was a memoir penned by aviator Ernest K Gann, the stories contained in that book have given rise to a number of movies but this particular film just borrows the title. Maybe Gann himself was unhappy about the result but the movie is attractively shot by Milton Krasner, has a score by Jerry Goldsmith which manages to be both haunting and lush, and is thematically consistent in a way that is satisfying.

Ford plays it low-key for the most part, a quiet performance that suggests maturity and fits his character. Taylor could be big and showy on occasion all through his career, but he too had a quietness, an introspective side that he was able to tap into and it serves him well at a few key moments. The piecing together of the various facets of a man’s life and character through the vignettes presented in the flashbacks allows a succession of performers to drop in and sketch a few more lines in the emerging portrait of Savage. Mark Stevens’ noir heyday had passed yet he brings a fine sense of weary dissipation to the role of an alcoholic former buddy who owes much to Savage. Dorothy Malone ( The Tarnished Angels)gushes glamorously as a socialite ex-fiancée in a brief interlude, while Nancy Kwan (The World of Suzie Wong) has a slightly more substantial part and consequently adds a good deal more to our understanding of the pilot. Susanne Pleshette, on a good run around this time and only a year after co-starring with Taylor in Hitchcock’s The Birds, brings a touching bewilderment to it all, wondering why she should have been singled out to live when everyone else perished. She was an actress who always had a gutsiness about her and that aspect is on show when she has to confront her fears and thus make perhaps the vital contribution to the final resolution.

Fate Is the Hunter is the kind of film that isn’t quite what it seems to be on the surface. There is aviation drama to satisfy those drawn to the title by that aspect but that’s only incidental I’d say. At heart, the movie is about perceptions and assumptions, how chance and belief can combine to shape a life, how one’s impressions and suppositions may not be as dependable as we hope, and how reason can transcend the random while also bolstering faith and friendship.