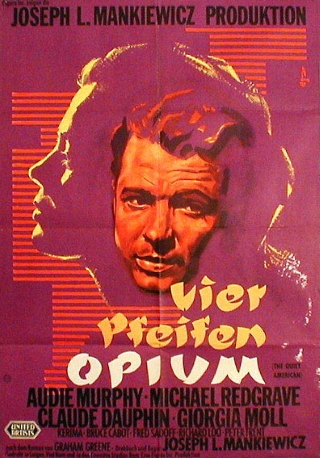

The Quiet American (1958) is an adaptation by Joseph L Mankiewicz of Graham Greene’s novel of the same name and it, unintentionally from the filmmaker’s point of view, poses the question of whether a movie is best approached or evaluated on an emotional or an intellectual level. Greene was very unhappy with the changes Mankiewicz made to his book, particularly with the alterations to the political sentiments the author had written into his story. Greene’s objection highlights what I think of as the intellectual approach, for viewing a film and assessing its worth or success in terms of its political perspective strikes me as a coldly intellectual exercise. Conversely, examining how a movie deals with the human interactions that underpin the story is surely a more emotional approach. Given that I have long been convinced that art is much more closely related to the heart than the head, it probably won’t come as any surprise to learn which view I tend to favor.

The Quiet American opens near the end of the story and works back from there in search of a beginning that will allow all the events and personalities involved to fall into place. The titular character (Audie Murphy) who remains unnamed throughout, unlike in Greene’s novel, is already dead when we viewers come on the scene. His body is floating face down near the banks of the river in Saigon, discovered by chance by revelers celebrating Chinese New Year. From here we are taken back to the months before his demise, to the time when he first arrived in Vietnam. So the bulk of the movie is related via flashback, unfolding from the point of view of Thomas Fowler (Michael Redgrave), a British journalist and acquaintance of the anonymous American, as he conducts a one-man wake in the morgue, reflecting on the life and death of the young man reposing on the slab before him. Those few months defined the course of the lives of three people: Fowler, the American, and Phuong (Giorgia Moll), the young Vietnamese girl who is loved by both of them. Regardless of the political background of the tale, and the points about the role of foreign intervention in South East Asia that Greene wanted to make, this is a love story first and last; remove that element and there is nothing to relate that has any resonance beyond contemporary concerns. What matters here, and what the movie focuses on, is the triangle formed by those three people, with Phuong acting as the anchor.

As I mentioned above, Greene felt aggrieved at the way the script radically altered the points he wanted to make in his book. I can understand that frustration on the part of the author, and I can sympathize with what he must have seen as wholesale distortion of his vision. I read and enjoyed his novel many years ago yet I still appreciate this movie for what it is, for what it does rather than what it does not. Basically, I see the changes that Greene disliked as only background details as far as the movie is concerned – those elements might be integral to the aims of the novel, but Mankiewicz was making a movie and both his medium and the aims he had were very different. I am of the opinion that any filmmaker who emphasizes the purely contemporary elements of a story at the expense of the timeless aspects is straying into the realms of commentary. In short, I see film as a form of artistic expression, an analysis of the human condition, and that is something eternal rather than ephemeral.

Ultimately, what counts is whether or not the movie works on the terms by which it was conceived. I regard it mainly as both a love story and as a contemplation of the way we frequently project visions of ourselves and the world around us onto those we love. As such, I consider it to have succeeded in achieving it aims. Of course one can dig deeper and read more into it all, seeing different slants on relationships adopted by the old world and the new, the contrasting views of young and old, and so on. Nevertheless, it all comes back to the portrayal and interpretation of love and what that means to various individuals in the end. The background of the story operates in relation to the characters like the MacGuffin in a Hitchcock film, but even then only up to a point. After all, when Fowler makes his fateful decision, he is motivated by a toxic cocktail of pride, jealousy, fear and thwarted passion and not something as prosaically dreary as political convictions.

On paper, one would say that having Audie Murphy face off against Michael Redgrave would lead to an uneven and unfair contest. On celluloid and in fact , however, the contest is a remarkably even and productive one. Murphy had grown steadily as an actor by the late 1950s and this kind of dramatic role was well within his capabilities. There is still a lot of fresh energy about him, and that quality is used to superb effect when placed in contrast to Redgrave’s worn and dissipated cynicism. That fresh faced enthusiasm always cloaked a deeper steel and there is never any doubt about the resilience of the idealistic young man he was portraying. When he trades words with Redgrave’s weary writer, the latter may indicate disdain for their naivety but he never really questions their sincerity, and nor do the viewers. Redgrave is every bit as good as the complete opposite, a tired and spent man whose surface smugness masks chronic insecurity and desperation. We believe it when Murphy shows drive and positivity, and that sense of credibility is just as strong when Redgrave paints his own picture of desolation and emptiness.

Italian actress Giorgia Moll is wonderfully unknowable as the focal point for the affections of those two very different men. There is a lot of passivity about her character, right up till the end anyway. Her final scene adds a great deal of punch and power though, largely because of the apparent indifference and insouciance she displays earlier. The cast is fairly self-contained, but Claude Dauphin lends attractive support as the deceptively relaxed policeman who misses very little. Bruce Cabot has what amounts to a cameo as an American journalist and Richard Loo, who popped up all over the place throughout the 40s and 50s whenever an Asian character was required, is coolly efficient as Redgrave’s contact with the insurgents.

The Quiet American was given a release on Blu-ray by Twilight Time some years ago but I never got around to picking it up and have had to make do with less than stellar DVD versions. It’s a shame no company in the UK has been able to put this film on the market on BD so far. The story was filmed in 2002 by Philip Noyce, with Michael Caine and Brendan Fraser in the Redgrave and Murphy roles, and it stuck closer to the sentiments of the novel. I saw it at the time and while I thought it was fine (although I should say I’ve never been able to warm to Fraser in anything) I don’t think it was improved by being more faithful to its source. I can only say that I have never felt the need to revisit the 2002 film in twenty years whereas I’ve seen the Mankiewicz version multiple times.