A man needs a reason to ride this country…

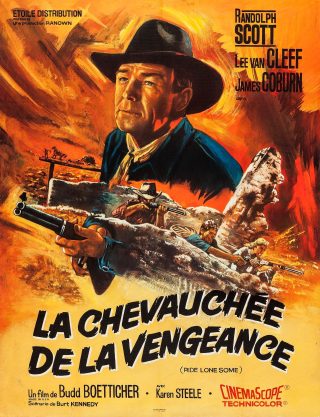

In Ride Lonesome (1959) the reasons are vengeance, bounty and amnesty. The penultimate Ranown western serves up all three but the focus remains firmly on the first. The notion of a lone man driven on by the pain of a past trauma is a recurring theme in Boetticher’s westerns, and is explored in depth in Ride Lonesome. Of the seven films Boetticher and star Randolph Scott made together, I would say this is the best; the plot, dialogue, imagery and performances all mesh to perfection. Nothing is wasted in this picture, where every shot, every gesture and every word is loaded with significance.

The viewer is immediately pitched into the action from the opening shot of the starkly familiar rocky landscape of Lone Pine, and the tension and pace never let up until the final credits roll. Ben Brigade (Scott) is introduced as a lone bounty hunter, and within minutes of appearing on screen has captured a young outlaw. Moving on to the nearest stagecoach swing station, with the outlaw’s brother in pursuit, he finds himself in another dangerous situation. The only occupants are the station master’s wife (Karen Steele) and two wanted men, Boone and Whit (Pernell Roberts and James Coburn), looking to find a way out of their current situation. Turning in the young prisoner would allow them to take advantage of an offer of amnesty, but that also necessitates their disposing of Brigade. The lone hero now finds himself part of an uneasy group and facing threats from three fronts; his new companions, the chasing pack of outlaws and a rampaging Mescalero war party. As the story progresses it becomes apparent that Brigade’s determination to see his captive to Santa Cruz, and an appointment with the hangman, is only part of his motivation. It’s fairly clear that the boy is merely the bait with which Brigade hopes to hook a bigger and more personal catch, although the exact reason for this isn’t revealed until the climax. In these moments, as Brigade stands and gazes impassively at the twisted hanging tree, the full power of the tale strikes home. The cold, unemotional hunter of men is no longer just a bounty killer but a figure lifted straight from classical tragedy.

Ride Lonesome offered Scott one of his harshest characters in Ben Brigade. There’s very little humour on display and even in those moments when he shows some modicum of tenderness towards Karen Steele it’s of the gruff and brusque variety. However, this is absolutely in keeping with a man who’s carrying around deep scars. Burt Kennedy supplied him with his finest, most distinctive dialogue and Scott delivers it in a suitably terse fashion. Pernell Roberts and James Coburn (in his screen debut) are excellent as the bad men who aren’t all bad – the real villain of the piece is Lee Van Cleef, and the only complaint that could be made about him is that he gets so little screen time. Karen Steele looks good and plays the typically tough and stoical Boetticher heroine whose only moment of weakness comes when she learns the fate of her missing husband. This was the director’s first film in cinemascope and he employs the wide lens to great effect. The action takes place exclusively outdoors and once again highlights Boetticher’s gift for disguising the limited budget he had to work with. There’s a Fordian quality to the tiny figures dwarfed by an expansive landscape which mirrors the scripts nods to the old master. Isn’t there something vaguely familiar about that story of the embittered, driven man on a vengeful quest only to find himself alone and apart from society at its end? There’s also a degree of religious symbolism in the climactic scenes with Scott standing before the hanging tree which resembles a crude cross. It’s as though he has borne his own cross for years and now returns to his personal Golgotha to lay the past to rest before the final cathartic act of burning the tree.

Ride Lonesome is another strong DVD transfer by Sony. Like the other titles in the Films of Budd Boetticher set, the colours are strong and true, and the picture looks suitably filmic. There is a commentary track provided, and another of those short featurettes with Martin Scorsese. As I said earlier, I think this is the best of the lot – Boetticher’s finest film, and a real treat for western fans.