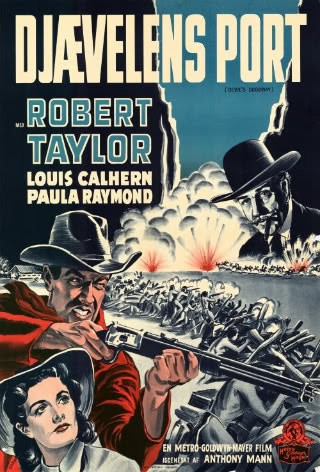

Before 1950 the injustices visited upon the Native American people were essentially ignored, or at the very least only touched on, in the cinema. However, in the space of a year two major Hollywood productions would use the plight of the Indian as their central theme. Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow was notable for its sympathetic portrayal of the Apache, but Anthony Mann’s Devil’s Doorway (1950) went even further by concentrating on the naked and ugly racism confronting those Indians who had done their best to embrace the ways and laws of the white man. It’s a much more tragic film than Broken Arrow and consequently more powerful; the fact that this power remains undiminished even for a modern audience demonstrates just how radical a picture this must have been sixty years ago.

Lance Poole (Robert Taylor) is a Shoshone who has decided to adopt the classic American mindset i.e. looking to the future rather than dwelling on the past. Not only has he anglicized his name but he has also taken a huge leap of faith by enlisting in the white man’s army and fighting in the Civil War. Returning home to Wyoming as a highly decorated veteran (having won the Congressional Medal of Honor no less), he is full of optimism and hopes for a bright future. He’s confident that the recent horrors of the battlefield will have purged the nation of its desire for further bloodshed. However, soon after his triumphant return he has to face the fact that not everything or everyone has changed as much as he might have hoped. The old grudges and prejudices still live on in the hearts of some, notably an eastern lawyer, Verne Coolan (Louis Calhern), who’s moved to Wyoming for his health. Coolan’s snide comments are only a foretaste of what’s to come though, as the local doctor’s refusal to attend to Poole’s ailing father until it’s too late proves. While Poole busies himself building up his cattle ranch and his fortune, Coolan is angling for a chance to seize the ancestral land and teach the red man a lesson on climbing above his station in life. Coolan’s opportunity comes with the Homestead Act, which allowed for the breaking up of former tribal land into individual claims, and he encourages a mass migration of sheepmen in the hopes of forcing Poole off his land. Although Poole is initially persuaded to hold his fire and try for a compromise by female lawyer, Orrie Masters (Paula Raymond), the scene is set for violent confrontation between the Shoshone and the sheepmen that Coolan is ruthlessly manipulating. As tensions rise, and the viewer’s outrage at the double standards and open bigotry on display similarly escalate, Poole must finally concede that his dreams of peaceful co-existence are nothing more than the foolish longings of a man too eager to buy into the glib promises of pragmatic politicians. When he dons his old uniform, with his medal proudly pinned in place, to face the same army that he once served with distinction there is a poignancy and irony that drives the message of the film home most eloquently.

Anthony Mann had spent the 40s building up his reputation with a series of tight little noirs frequently lensed by master cameraman John Alton. Both men brought their style and sensibility to a western setting in Devil’s Doorway. Given Mann and Alton’s background it’s not altogether surprising that the movie has both the look and feel of a film noir; there are plenty of dark, shadowy scenes and an abundance of low angle shots. One scene that highlights this perfectly is the fist fight that Poole is goaded into in the saloon by Coolan and one of his cohorts. Everything is shot in the cramped confines of the bar with smoke and shadow blending together as the two men hammer each other savagely – there’s no musical accompaniment to distract from the sound of the punches landing, and the quick cutting alternates between the increasingly battered faces of the fighters and the even more grotesque visages of the rubbernecking customers. Having said that, there’s no shortage of more traditional genre imagery either, and Mann demonstrates a breadth of vision and skill with large-scale action scenes that would be further developed in both his later westerns and epics. For me, Robert Taylor was convincing as the Shoshone warrior caught between two camps. He injected a huge amount of humanity into the role of Lance Poole and produced a fully rounded character that transcended the “noble savage” caricature. I guess the black and white photography helps, but I never caught myself thinking that this was just a guy in dark make-up playacting. Louis Calhern also did sterling work as the slimy lawyer who uses convenient statutes as a means of disguising his own prejudices. Paula Raymond was good enough as the woman caught in the middle, but the script shies away from depicting an all-out romance with Poole – the movie was in all honesty already pushing the envelope as far as could be expected for the era. I might also mention the strong support particularly from Spring Byington and Edgar Buchanan.

Currently, there are only two editions of Devil’s Doorway available on DVD. There is an MOD disc from the Warner Archive in the US and a Region 2 pressed disc from Warner/Impulso in Spain. From the perspective of international customers neither one is ideal – the US disc being both expensive to acquire and on potentially suspect media, while the Spanish release is exclusive to El Corte Ingles for who knows how long with the attendant shipping costs. I viewed the Spanish disc, and the transfer is generally a strong one with good contrast and detail. However, it is unrestored and there are the usual scratches, nicks and blemishes – though never to the point of distraction. There is English and Spanish audio with removable Spanish subs. The disc comes in a slip case with a 34 page booklet, in Spanish naturally, that contains a very nice selection of still photographs and original advertising material. When one considers the development of the western, and the career of Anthony Mann too, this is an important title. As such, it’s disappointing that it should be marketed so restrictively on both sides of the Atlantic. However, the Spanish disc does at least afford the film a degree of respect that’s lacking in the US release. Devil’s Doorway seems to have got lost between Mann’s earlier noir pictures and his subsequent psychological westerns, but it actually acts as something of a bridge. It’s a film that’s intellectually and emotionally satisfying while it also provides solid western entertainment. Recommended.