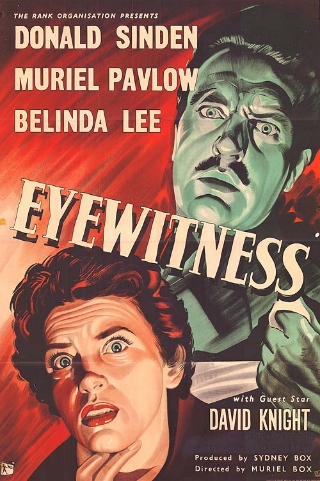

Lots of different things draw us to movies. Personally, I’ve always been a fan of Gothic mysteries, particularly those where the Hollywood majors cooked up that special atmosphere that could only exist within the carefully crafted confines of a studio set. Add in a rare adaptation of the writings of John Dickson Carr and I’m hooked. The Man with a Cloak (1951) combines both of these elements, and it was a film that had intrigued and eluded me for years. It’s been quite some time since I read Carr’s short story The Gentleman from Paris, but I remember enjoying it and was keen to see how the film version worked.

It’s 1848 in New York, the year that saw revolutions breaking out in so many parts of the world. Against this turbulent backdrop a young woman arrives in the US seeking help. She is Madeline Minot (Leslie Caron), a somewhat unlikely fundraiser for a political cause. Her mission is to seek out the assistance of her fiance’s uncle, Charles Thevenet (Louis Calhern), now living in dissipated and debauched exile in the wake of Napoleon’s downfall. Madeline had been expecting to be introduced to a distinguished gentleman, instead she finds a half-crippled drunkard seeing out his days in decaying splendor. Thevenet’s alcohol sodden existence is being overseen by a trio of servants and retainers under the supervision of Lorna Bounty (Barbara Stanwyck). Two things are clear right away: Madeline’s presence is unwelcome in this household, and Thevenet’s protectors are no more than vultures patiently circling their dying master. And so it all comes down to money, Thevenet’s got it and everybody else wants it. While Madeline cannot prove that Lorna and her cohorts are actively plotting to murder the old man, she knows that it’s clearly in their best interests to see that he doesn’t hang around long enough to make any changes to his will. Into this little circle of greed and deceit steps Dupin (Joseph Cotten), the mysterious poet of the title who spends his days cadging free drinks from a sympathetic barkeep. Dupin isn’t motivated by the promise of money, though he’s clearly badly in need of it, rather he’s drawn to the simple faith in life of Madeline and a desire to see an injustice averted. It’s Dupin’s arrival that forces Lorna’s hand and brings the two mysteries of the film center stage: the puzzle of Thevenet’s will, and the real identity of the enigmatic poet.

The Man with a Cloak was directed by Fletcher Markle, a man who is probably better known for his television work. There are some highly effective scenes and a handful of noteworthy visual flourishes, and yet I can’t help feeling that the potential of the story and its setting weren’t fully exploited. The film has that polished look that MGM typically brought to its productions, and the studio sets are faultless. Still, the tension is allowed to slacken too often and that’s partly down to the failure to make the most of the visual opportunities. As for the plot, it’s solid enough but it’s perhaps overly dependent on building up an aura of mystery around the character of Dupin. While it’s adapted from a reasonably entertaining Carr story, it’s not one that highlights the author’s real strengths. In short, there’s arguably too much emphasis on who Dupin actually is – the film is liberally sprinkled with clues and it shouldn’t prove all that difficult to work out for any fairly literate viewer.

While the direction and scripting of the movie are always competent, they are nothing exceptional either. What does give the film a boost though is the acting. Both Stanwyck and Cotten were seasoned professionals, capable of tackling a variety of roles. Cotten spends most of his time hovering around the borders of sobriety, and gets to deliver some witty and telling lines. His character displays a weary cynicism, a sort of metaphorical cloak for the unnamed sadness he carries within himself. Against this is ranged the steely pragmatism of Stanwyck. Her outer gentility and polish masks a barely repressed sensuality and a deep streak of bitterness – after all, we’re talking about a woman who feels she has been robbed of ten of the best years of her life. While Cotten and Stanwyck rarely put a foot wrong, Louis Calhern almost effortlessly steals just about every scene. I sometimes think that if you want to capture a visual representation of regret for a life of unfulfilled promise, then you need only watch one of Calhern’s performances from around this time. In the face of such stiff competition, Leslie Caron fades into the background most of the time. It’s not that her portrayal of a frightened and confused ingenue is especially poor, just that she lacks the presence to make her mark among these heavy hitters. It’s a rare film that doesn’t benefit from a strong supporting cast, and The Man with a Cloak is no exception. Margaret Wycherly looks like she had a ball as a cackling old crone, and Jim Backus is a delight as the Irish bartender trading philosophical jibes with Cotten.

The Man with a Cloak was until recently another of those films that I began to think I was fated never to see. However, it became available via the Warner Archive, and shortly afterwards was given a pressed disc release in Spain via Llamentol. I watched the Spanish disc the other day and, judging from some screen captures I’ve seen, it looks like a clone of the US disc. Generally, the transfer looks pretty clean and sharpness and contrast are quite acceptable. This release offers no extra features whatsoever, just the film with its original soundtrack and the option to watch it with or without Spanish subtitles. I’ve seen people allude to the film’s noir credentials before but I feel the link is tenuous at best, and it’s not a title I’d be comfortable labeling in this way. For me, The Man with a Cloak is simply a Gothic mystery with a generous dollop of melodrama added. Overall, I found this an enjoyable and entertaining movie, though it’s not without its faults. I guess the presence of some big name stars and the fact it was sourced from a John Dickson Carr tale raised my expectations perhaps a tad too high. Nevertheless, I couldn’t say I was especially disappointed. If the direction is a little flat at times, the performances do compensate. Anyone who enjoys these studio bound mysteries, likes Carr’s writing, or is a fan of Stanwyck and Cotten should find enough to satisfy them here.

Those seeking another take on the film should pop over to Paul’s place at Lasso the Movies.