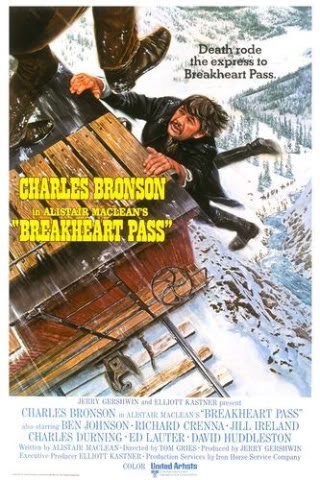

A Charles Bronson western written by a Scotsman and combining elements of a whodunnit and an espionage thriller sounds very much like a recipe for disaster. Despite that, Breakheart Pass (1975) actually works quite well; it’s never going to be considered a classic but it is wonderfully entertaining and looks great. A fine cast and some first class talent behind the camera have a lot to do with this of course. For me, the fact that a significant part of the action takes place aboard a train adds to the pleasure, as I’m a huge fan of anything that exploits the dramatic possibilities of having a group of suspicious characters all cooped up together and denied the opportunity to escape.

A military train carrying reinforcements, and medicines is bound for Fort Humboldt, where a diptheria epidemic is raging out of control. Aside from soldiers, there’s a number of civilian passengers aboard, all with official reasons for being there. Their numbers are swollen right at the beginning though when Marshal Pearce (Ben Johnson) muscles his way through the protocol in order to get both himself and his newly acquired prisoner, a wanted murderer and arsonist, John Deakin (Charles Bronson) a couple of berths. Before the train has even pulled away from the halt two army officers have mysteriously vanished, and it’s clear from the shifty behaviour of practically every passenger that nothing is quite as it seems. While the locomotive chugs its way towards the stricken fort the unexplained incidents, and the bodies, start to pile up ominously. The senior army officer, Major Claremont (Ed Lauter), is growing uneasy while the Marshal and the most prominent passenger, Governor Fairchild (Richard Crenna), seem reluctant to treat matters as anything more than ill fortune and coincidence. All the while, Deakin moves surreptitiously from carriage to carriage pursuing some undefined agenda of his own. It’s only when the troop cars are sheared off and sent careening away into mid-air and subsequent carnage that it becomes clear to everyone how grave the danger is, and that a ruthless killer is in their midst. The movie trades heavily on the fact that all the passengers are potential suspects; it’s a constant guessing game for the viewer to try to figure out who’s behind the ever increasing mayhem. Just about everyone appears to have something to hide yet it’s difficult to see how any individual could wreak such havoc. Of course all is eventually revealed before a slam bang finish draws the curtain on an hour and a half of solid entertainment.

Most of Alistair MacLean’s books which were adapted for the big screen have something to keep you interested. While his writing was fairly formulaic, it’s not hard to see why so many of his stories ended up being filmed; they tend to have a cinematic quality in that the plots are definitely to the fore and the characters usually have a shadowy aspect that’s only gradually revealed. The biggest failing tends to be in the dialogue, his later work suffering especially. Breakheart Pass has a few such instances, when characters come out with lines that just don’t ring true in any way. Director Tom Gries had already directed a couple of very enjoyable westerns, the one of particular note being Will Penny with Charlton Heston. His shooting of the action scenes is hard to fault and, apart from the free-for-all finale, the fight atop the moving train is one of the best parts of the movie. Bronson and former light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore get to slug it out in an excellently choreographed scene that’s tense, exciting and real looking – no doubt the presence of the great Yakima Canutt, as stunt coordinator had something to do with it too. Of course, the aforementioned crash of the runaway troop cars is another of the big set pieces that’s both mesmerizing and horrifying. Furthermore, Lucien Ballard was on lens duty and, as you would expect, the photography of the outdoor scenes is quite spectacular. And rounding out the crew is Jerry Goldsmith, who provided another of his memorably upbeat scores that draws you in from the moment the title credits roll.

As far as the acting’s concerned, Bronson is his usual laconic self, speaking only when there’s a need to but holding off on the physical stuff for long stretches. His character is no brainless lug and he plays him with restraint and enough thoughtfulness to make him believable. Although the wife was also in the cast there’s, mercifully in my opinion, no contrived romance to take the attention away from the twisty plot. Ben Johnson is always a pleasure to watch and just got better and better with age. His character isn’t the best defined one that he played but he still manages to make his mark on the movie – all his little gestures and his characteristic delivery keep reminding you that you’re watching a genuine westerner in action. Richard Crenna and Ed Lauter, as the Governor and the Major, have just enough oily charm and nervy anxiety respectively to keep the viewer guessing about their motives too.

MGM’s UK DVD of Breakheart Pass is a reasonably good effort. The anamorphic transfer is the kind that’s not especially remarkable but doesn’t have any major issues either. The colour looks true enough to my eyes and there’s no notable damage to the print – the image doesn’t pop off the screen but nor does it disappoint. The only extra included is the trailer, along with a variety of subtitle options. So, we’re talking here about a movie that’s best described as good, competent entertainment. It doesn’t offer anything groundbreaking but there are far worse ways to spend an hour and a half. It’s the kind of film that will obviously grip the viewer more the first time it’s seen, however, there’s enough in the action scenes, acting and visuals to ensure it’s worth revisiting.

There haven’t been too many westerns that are set around Christmas, in fact I’m struggling to think of any others apart from 3 Godfathers (1948) and the earlier versions of the same story. While it starts out as a fairly standard western it soon turns into a play on the nativity story and the journey of the three wise men. It’s one of John Ford’s more sentimental pieces and the symbolism is laid on a little thick at times, but the cast and visuals carry it through the sticky patches. I’ll grant that the whole thing can seem a bit contrived yet the story, and its message of redemption and the good that lurks within all of us, remains affecting.

There haven’t been too many westerns that are set around Christmas, in fact I’m struggling to think of any others apart from 3 Godfathers (1948) and the earlier versions of the same story. While it starts out as a fairly standard western it soon turns into a play on the nativity story and the journey of the three wise men. It’s one of John Ford’s more sentimental pieces and the symbolism is laid on a little thick at times, but the cast and visuals carry it through the sticky patches. I’ll grant that the whole thing can seem a bit contrived yet the story, and its message of redemption and the good that lurks within all of us, remains affecting.