Some things a man can’t ride around…

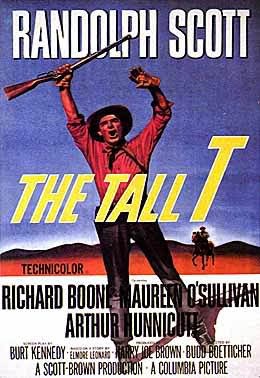

The first official entry in the Budd Boetticher / Ranown cycle of westerns is The Tall T (1957). The story here was adapted by Burt Kennedy from an Elmore Leonard short story called The Captives. That makes for an impressive set of credits and, in truth, the end result is a near perfect film. Once again Boetticher and Kennedy boil the western down to its absolute essentials, and the bulk of the action involves just five people and how they all relate to one another. Everything from location and plot to dialogue is pared right down and the film is all the better for that. What is left is a raw and visceral western with a strong moral current running through it and characters who we actually care about.

For a film with a short running time – under 80 minutes – it’s really a story with two distinct parts. The opening section introduces the character of Pat Brennan (Randolph Scott), a happy-go-lucky type in the process of building up his newly acquired ranch. He comes across as a gently charming sort who stops off on his way to town to pass the time of day with the local stationmaster and his young son. He even takes the time in town to pick up some candy for the boy as he had promised to do. When he visits his former employer, and loses his horse in an ill-judged wager, you start to wonder how such a hapless innocent could survive in a harsh environment. It is from this point on though that the depth of Brennan’s character begins to become apparent. Hitching a ride on a private stagecoach, hired for the honeymoon of Mrs. Mimms (Maureen O’Sullivan) and her gold-digging chiseller of a husband, he stops off to deliver the candy to the stationmaster’s boy. The station has been taken over by outlaw Frank (Richard Boone) and his two sidekicks (Henry Silva and Skip Homeier) with the aim of holding up the regular stage. Faced with the horror of what has just taken place, and the likely fate awaiting him and the other hostages, the character of Brennan undergoes a sea change. Almost immediately the easy-going ex-ramrod is transformed into a cool, calculating avenger who knows he must now play for time while waiting for the opportunity save himself and the woman. It’s a credit to all involved that this transition appears so natural as to be nearly seamless.

Scott’s flinty features once again blend in with the bleak Lone Pine locations which dominate the picture. The character shift I mentioned is magnificently achieved in the scene where the fate of the stationmaster and his boy is revealed in cold, matter-of-fact fashion by Henry Silva. Scott’s face hardens almost imperceptibly yet the meaning is all too clear. This kind of thing makes for great screen acting and the lead was a pastmaster in the art of underplayed emotion. Richard Boone was always interesting to watch, and in Frank he gives a fascinating performance as the outlaw you want to sympathise with. When he dispatches Mrs. Mimm’s husband, whose craven character offends his own personal morality, it’s difficult not to feel some grudging admiration. The two subsidiary villains are of less interest, but Silva manages to tap into a vaguely detached psychosis that works very well. Maureen O’Sullivan has an unglamorous role which offers her the chance to play something which is a cut above the standard damsel in distress. The fact that we get such well rounded characters in a short run time speaks volumes about the writing skills of Burt Kennedy. Boetticher again excels at making a cheaply produced picture look far more expensive. The framing and camera placement are miles away from the usual point and shoot style employed in low budget fare; this man had a real flair for the quirky and the unexpected. His handling of the action scenes is again exemplary, and they have both a frankly brutal quality and an odd humanity that make them stand out from other pictures of this vintage. There’s something deeply satisfying about Randolph Scott turning to the sobbing woman at his side, after the violent climax, and quietly intoning: Come on now, it’s gonna be a nice day.

Sony’s presentation of The Tall T on DVD is another excellent one. Some may carp at the amount of grain on view but I don’t regard that as a bad thing. The anamorphic widescreen picture is bright and colorful throughout. The disc also carries a short featurette with Martin Scorsese praising the film. Best of all, there’s the feature length documentary Budd Boetticher: A Man Can Do That. So, we get a great movie which is presented with care and respect – what more could you ask for.