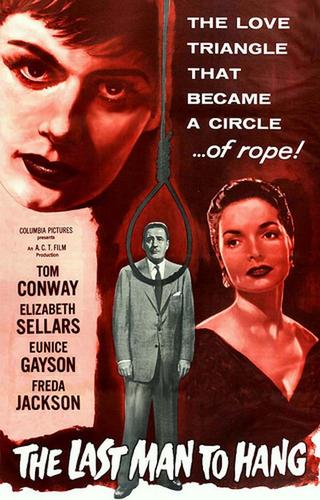

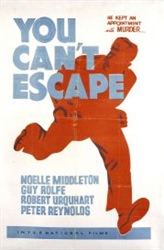

Somehow, without consciously having planned to do so, I’ve seen myself on a British thriller kick this summer and therefore embarked on this series of short pieces to log my thoughts and impressions as I’ve been going along. There hasn’t been any particular pattern followed but I have permitted certain films to lead me on to others, linking them up in a vague and loose form that probably makes little sense to anyone apart from myself. I appreciated Guy Rolfe in You Can’t Escape, had a fine time with Lance Comfort’s Tomorrow at Ten, and just recently enjoyed Terence Fisher’s direction of The Last Man to Hang. Those titles and the others I’ve been highlighting are all either films noir or crime/mystery pictures of one kind or another. All of this leads me to Home to Danger (1951), a film noir/whodunit hybrid starring Guy Rolfe, produced by Lance Comfort and directed by Terence Fisher.

Barbara Cummings (Rona Anderson) is the one coming home and the danger referred to lies in the stately pile she has just inherited from her late father. She’d been in Singapore and had left England under something of a cloud and so she feels a certain reticence about her arrival back in the family residence, particularly when she learns the inquest into her father’s death recorded a verdict of suicide. There’s a touch of guilt there but not too much – she knows she wasn’t responsible and no=one seems keen to attach any blame in that direction. However, it’s also clear that late changes to the old man’s will meant Barbara comes into everything of value, while some others who might have had what could be termed expectations have been either cut out at the last minute or not had the chance to be included. Although Barbara has an ally and someone to look out for her in the shape of debonair author Robert Irving (Guy Rolfe), there is a very real sense of menace following a botched attempt on her life. The question is who is behind it all, and what’s their motive?

Home to Danger is one of those slightly unusual amalgams of the country house whodunit and an urban film noir. The former characteristics are to the fore in the earlier stages following the new heiress’ return home. Terence Fisher gets good mileage from the manor house surroundings, and moves his camera around atmospherically, also creating some memorable and noteworthy visuals during the shooting of the exteriors. The action then switches back to town for a time in the course of the investigation into extremely dubious shooting. Again, Fisher is to be commended for altering the style appropriately and presenting different, but equally effective, imagery. The plot is entertaining and engaging enough and the director ensures, with the aid of those shifts back and forth in location, that the hour or so running time is full of incident.

Rona Anderson and Guy Rolf make for an attractive leading couple. Anderson has vigor and guts, and a quality which makes one want to root for her. Alongside her is the suave and assured Rolfe, winning viewer sympathy every bit as effortlessly. The likes of Francis Lister and Alan Wheatley drift in and out of the shadows and keep us guessing as to their real aims. A little further down the cast list is a young Stanley Baker, making the most of his smallish but vital role as a faithful and simple servant, hinting at the great things still to come later in his career.

Home to Danger should be easy enough to locate. It is available on DVD as part of a double bill with Montgomery Tully’s Master Spy in the UK via Renown. As far as I know, it’s also been released in the US as part of a set of British thrillers from a few years back. The transfer is mostly OK; although there is some weird shimmering effect that I noticed early on, it seems to settle down as the film progresses. The movie itself is a modest enough affair which, nevertheless, manages to pull off all it sets out to do. It tells a good crime story efficiently in a little over an hour, with an attractive cast and professional and stylish direction by Terence Fisher.