He fights his way, I fight mine. We’re just a couple of dogs haggling over the same bone. Only it happens to be his bone.

Whenever anyone tries to tell you that the westerns of the classic era were simplistic, one-sided shoot-em-ups that glossed over the complexities of the era they depict you could do worse than point to a line such as that highlighted above. The truth is of course that there are numerous examples of westerns in the classic era, especially in the genre’s golden years of the 1950s, which took a grown-up approach to the various injustices suffered, to the prejudices and fears of all involved, and thus embraced the consequent nuances of a fascinating period of time. Trooper Hook (1957) is a movie whose limited budget places no constraints on the intelligence of its script, or on the sincerity of its central performances. And it also exposes the redundancy of boilerplate dismissals of the genre’s depth by those who allow self-righteousness and a judgmental turn of mind to blind them.

Executions and reprisals, a harsh and uncompromising way to begin any story, but one which sets the tone for what will follow. That is not to say Trooper Hook is a movie of gratuitous or even excessive violence, rather it is a picture which frankly examines an enmity which is implacable and deep seated. The executions are of the straggling survivors of the first wave of an army assault on an Apache settlement. The battered and beaten soldiers are backed up on a bluff above the village as the Apache leader Nanchez (Rodolfo Acosta) calmly has them shot down one by one. Almost immediately, the next wave of cavalry troops descend on the Apache, round them and their families up and burn their settlement to the ground. Among the prisoners awaiting transportation to the fort, and ultimately the reservation, is a white woman and her young son. This is revealed to be Cora Sutliff (Barbara Stanwyck), the only survivor of a raid who was subsequently taken prisoner and whose child is the son of Nanchez. Unsurprisingly, after years of captivity and rough treatment, she is largely unresponsive. Of course any long term hostage or captive is going to struggle to integrate themselves back into the society from which they were snatched. However, Cora’s future is even more in doubt since the world she knows is one riven by hatred. She endured and to some extent overcame the hostility of the Apache women but now is confronted by the equally ugly contempt and rejection of her own people. And then there is the boy, Cora is strongly protective of him, his father will not rest till he gets him back, and the whites largely want nothing to do with him. All but one man that is. Sergeant Hook (Joel McCrea), is a veteran campaigner, one who has known loss, hardship and desperation himself, and thus is a man loath to sit in judgment of others. His task is to escort Cora and the boy back to the husband she hasn’t seen for many years, and to head off any threats that arise, whatever direction they may come from.

Charles Marquis Warren was what I’d call an occasional director, devoting more time to writing and producing and doing so with great success, particularly on television with both Gunsmoke and Rawhide. His direction of Trooper Hook is fine as far as I can see, drawing a sense of intimacy from the interior scenes, especially those taking place in the stagecoach, and touching on that frequent western image of apparently tiny and insignificant human dramas playing out against the backdrop of a massive, primal landscape. Cinematographer Ellsworth Fredricks captures that expansiveness in the scenes shot on location in Utah, with his camera high among the craggy peaks alongside grimly impassive Apache warriors coolly observing the dash of the stagecoach far below on the dusty, arid floor of the canyon. Visuals aside, the strength of the movie lies in its theme of acceptance amid seemingly wall to wall hatred, as well as or maybe allied to the maturity of outlook that forms its core. It was adapted from a story by Jack Schaefer (Shane, The Silver Whip, Tribute to a Bad Man, Monte Walsh) so it’s pedigree is strong – this is taken from one of his short stories I haven’t read, but I intend to set that omission on my part right.

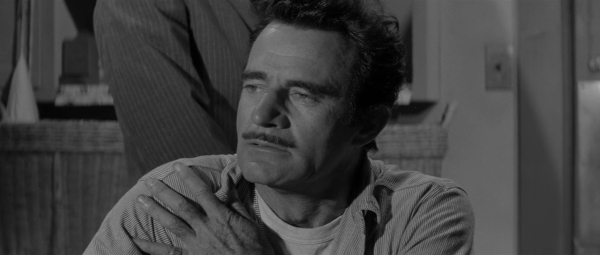

Much of the maturity underpinning the movie comes not only from the writing but also the casting. The two leads were over 50 years old at the time – Stanwyck was 50 and McCrea 52 – and both of them, in the last of a half dozen movies they made together, bring a lived-in credibility to their roles. Stanwyck achieves an extraordinary stillness in her early scenes, a watchful withdrawal that feels appropriate for a woman who at that point had to all intents and purposes been assimilated into the Apache tribe. Such is the layering of the role though, and therefore the performance, that her detachment is also right for someone who is just beginning to realize that hers is not to be a sweet homecoming, that her very survival will be taken as an affront by many. The way she tries to talk herself into believing the husband she has not seen for an age will accept not only her but her son too is a masterclass in pathetic self-delusion, and the despairing gaze she casts in McCrea’s direction as she babbles out this fantasy is telling. McCrea’s ageing soldier is decent, dignified and authoritative, all the qualities that make the western hero such an admirable figure; I think I’d actually go further and say he comes close here to epitomizing the traits and values that made the post-war US so admirable. The strength of Hook derives from his honesty, his warmth and his defense of the weak, his refusal to buy into cheap bigotry or cruelty. If only there were more of his type around in the world today.

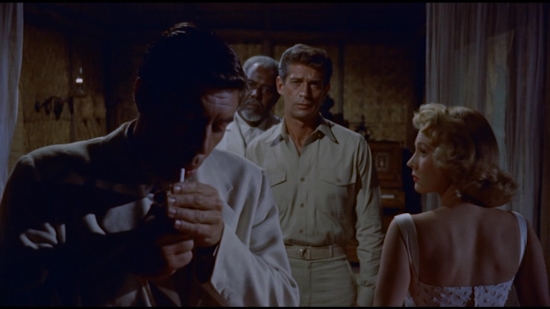

The film is imbued with this generosity of spirit, it’s reflected all through the cast. Earl Holliman’s itinerant cowboy, forever short of cash yet long on good nature, is another openhearted individual, prepared to take huge risks to ensure the safety of those who did him a good turn. It’s there too in the quiet courage of the passengers, particularly Susan Kohner, just off making The Last Wagon for Delmer Daves and only a year or two away from her Oscar nominated turn in Sirk’s Imitation of Life. Royal Dano is barely recognizable as the grizzled stagecoach driver but he too carries a strong sense of honor beneath that gruff exterior. By way of contrast, the ever reliable Edward Andrews essays the type of oily venality he brought to many a part. And John Dehner deserves credit for his portrayal of a man who cannot find it within himself to rise above his prejudices. That’s a tricky role, one that could easily slide into villainous caricature yet such is Dehner’s professionalism that he instead paints a picture that earns pity and scorn from the viewer in equal measure.

The only issues I have with the film are the somewhat redundant use of Tex Ritter’s song to punctuate the action onscreen, as well as the editing of the version I viewed. There is a choppiness to that editing, with scenes ending so abruptly that they are highly suggestive of a cut down print. I know there are some who don’t rate Trooper Hook so highly, but I’m an unashamed fan of the movie. There is so much of what I love about the classic western encapsulated here – the ability to tell a story that is rich and deep, that has meaning and soul, within a relatively simple framework. But more than anything there is that straightforward belief in the ultimate triumph of all that’s fine in the human heart, that steadfast faith in our capacity for being better despite the malice that may threaten us at times.