Confinement breeds volatility. And confinement, be it physical, emotional, spiritual or social, is a key element in film noir. As space is limited, so is the room for maneuver and so are the options available to the protagonists. This is provides a situation ripe with dramatic potential – take a small group of characters menaced by an external threat and simultaneously squeezed by internal pressures and sit back to watch what happens. This is the essence of Storm Fear (1955), and it’s a formula which has been employed on and off by filmmakers in productions as diverse as Day of the Outlaw, The Small Voice and Key Largo.

Storm Fear has its characters in uncomfortable places all the way through, right from the beginning when young David Blake (David Stollery) and Hank (Dennis Weaver), the hired help, come in from the snow, into the remote mountain cabin. David’s mother Elizabeth (Jean Wallace) is guarded and somehow restrained while her husband Fred (Dan Duryea) is even more detached. The mood and atmosphere of the cabin and its occupants is wrong, discontent and dissatisfaction pervade like some insidious form of emotional dry rot. Fred is a man bowed and broken by personal and professional failure, a shuffling, shambling figure forever burrowing deeper into the oversized scarf he twists and kneads, his comfort blanket in a world from which he has retreated. Elizabeth is a martyr to duty and disenchantment, going through the motions in a barren and loveless marriage. Suddenly, this chill facade is shattered by the arrival of Fred’s brother Charlie (Cornel Wilde). Charlie is a hood, a no-good type with a long history of crime following him around, and on this occasion he’s also got two accomplices in tow (Lee Grant & Steven Hill). He is on the run after a bank raid has netted him a sack full of money, a bullet in the leg and a looming murder rap. All of that ought to amount to a fair amount of pressure within and without yet there is the added complication of the tangled relationship which links Charlie, Fred and Elizabeth.

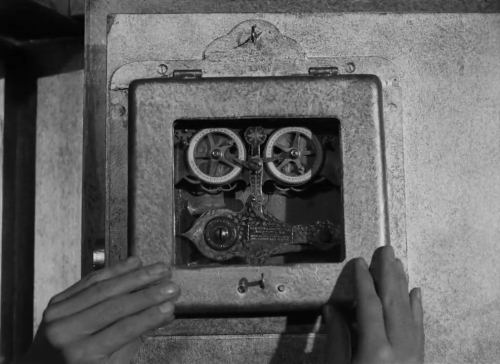

Cornel Wilde made his debut as a feature director with Storm Fear. He was also the producer and had Horton Foote adapt the novel of the same name by Clinton Seeley for the screen. In fact, Wilde assembled some impressive talent behind the cameras, with Elmer Bernstein providing the score and Joseph LaShelle taking care of the cinematography. As a result, this movie has a polished and highly professional look. Wilde paces everything well, drawing ample tension from the lengthy scenes within the cabin as the characters fume and feud. The climactic scenes out on the mountain, as the cold and weariness takes their toll, open things up somewhat, but that’s only in a superficial sense. The stark landscape and harsh conditions impose their own restrictions and in classic noir fashion the poor choices these people have been making throughout their lives narrow all their avenues of escape. It’s not so much a matter of being unable to stop what’s coming as being unable to outrun what went before.

Wilde’s acting is solid, he adds a slight stammer to his character’s delivery to indicate his core insecurity. It’s an affectation of sorts but it fits the character and he never makes it feel forced. Jean Wallace, who was married to Wilde, is especially strong in a difficult and multifaceted role. She is called upon to range from guilt and remorse to resilience and resolve. It amounts to a tricky balancing act on her part and she carries it off successfully all told. I guess most viewers will be accustomed to seeing Dan Duryea take on showy parts. As such, his portrayal of Fred Blake could be regarded as something of a departure. It’s a comparatively quiet role, contemplative and reproachful to the point of being ineffectual, with a hint of puritanism lurking below the surface. I’m not sure it works though. Lee Grant, making a rare screen appearance in the middle of those lost years when she was victimized by the blacklist, is almost unrecognizable as the bleached moll with a considerable thirst. I’ve seen largely positive reactions to Steven Hill’s turn as Wilde’s psychotic sidekick, but I can’t say I appreciated his work here. Hill was an alumnus of the Actors Studio and that is very apparent here. I’ve never been a fan of method acting although I’ll concede some such as Montgomery Clift made it work for them. Hill, a little like Rod Steiger at his most excessive, never leaves the viewer in any doubt that he is giving a Performance, and not for one moment did I feel he was anything other than an actor playing a part.

Kino released Storm Fear in the US years ago and it’s a handsome looking production. LaShelle’s crisp cinematography comes across well and the pacy, self-contained story never outstays its welcome. It’s a late-era film noir that harks back to the previous decade’s focus on personal rather than wider societal conflicts. While I have some reservations about a few of the performances, there are a lot of good things going on and the movie is certainly worth a look.