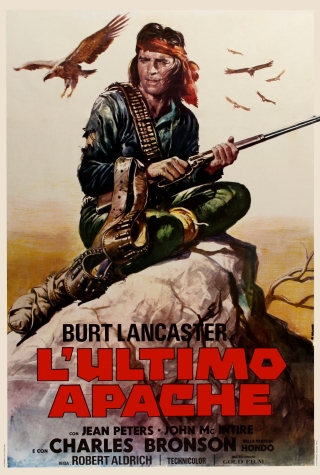

Which words get tossed around most often when the western is discussed? I guess I talk a lot about redemption, it’s the cornerstone of the genre for me. Others, depending on the direction from which they are approaching it, may look at the way it portrays expansionism, or how it charts and critiques civilization. Some like to focus on the elegiac aspects, and some go in for revisionism. But does anyone ever mention a sense of urgency? Maybe we should though. A lot of classic era westerns have a paciness to them, both for budgetary and for storytelling reasons. Yet when one stops to think not only of the relatively short window in time occupied by the historical concept of the Old West but also the equally brief flowering of the classic movie version, it somehow feels appropriate to regard urgency as at least one of the characteristics worth considering. Apache (1954) is what I would call an urgent movie. It is a motion picture in a very literal sense, the protagonist moves almost continually and it offers little respite for the viewer either as events unfold on screen. The theme too is one of an era drawing to a rapid close, of time threatening to overtake people and the consequent need to keep pace with it all.

It opens with the surrender of Geronimo, the end of the Apache Wars and to all intents and purposes the closing of native resistance in general. One man at least is not keen on this capitulation and the first view of Massai (Burt Lancaster) has him riding in aggressively in a last ditch attempt to disrupt the event. It’s as good an introduction of the character as one could wish for, highlighting his belligerence, defiance and energy. Nevertheless, despite his bullish bravado, he’s not to succeed. Instead he is manacled with the other former fighters and placed on board a train headed for Florida. Even as the locomotive makes it’s way across the country, Massai’s restlessness and rebelliousness remains undimmed. Taking advantage of a temporary halt in Missouri, and the hubris of embittered Indian agent Weddle (John Dehner), he escapes. This leads to a brief yet fascinating interlude where Massai spends some time wandering around town, bemused and ultimately threatened by a way of life that couldn’t be more alien to him. That sense of urgency, that driving need to return to his roots while he still can, kicks in again and his overland odyssey is broken only by an encounter with a Cherokee in Oklahoma who has resigned himself to the reality of the newly civilized world. It leads to a wonderfully droll moment where Massai asks incredulously how it is that he has a wife but has to fetch and carry the water himself. The old Cherokee looks at him ruefully and admits with a sigh that some of the ways of the white man are indeed hard. The lessons Massai has learned along the way have given him hope though, hope that he may find the means to continue to exist as a free Apache, albeit less warlike and in the company of his love Nalinle (Jean Peters). This is not to be, however, and the drunken duplicity of Nalinle’s father as well as the distrust of the army and scouts see him back in chains. All the while, the movement never ceases, the cross-country trek, the recapture and later escape, and then the long run to the wilderness of desert and mountain, the settling of old scores and the desperate effort to reclaim some shreds of the past before the relentless advance of civilization rends them forever.

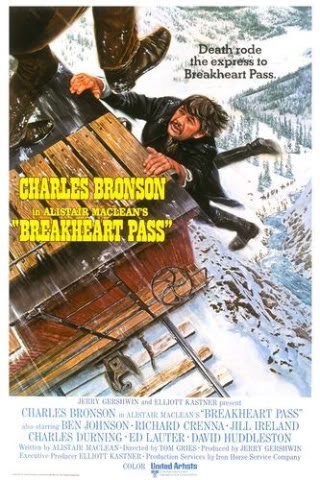

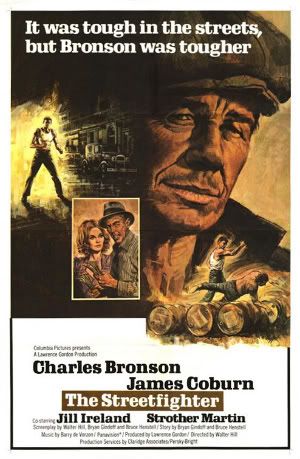

Apache fits neatly into that group of westerns taking a more sympathetic view of the native American that had begun to appear in the early years of the decade. This pro-Indian cycle set in motion and characterized by the likes of Anthony Mann’s Devil’s Doorway and Delmer Daves’ Broken Arrow played a significant role in the evolution and maturation of the western which was taking place at this time. No doubt there are those who will protest the casting of Lancaster and Peters, as well as Charles Bronson, Paul Guilfoyle, Morris Ankrum and others, as Native Americans but it’s no more than a reflection of the casting practices, and indeed the choices available, at that time. Anyway, my own take on any spats over inauthentic casting is that surely acting is the adopting of roles and the presentation of characters and their traits. I see it as striving for some thematic and dramatic truth, and reality be damned. Was the theater of the ancients any less valid or lacking in artistic integrity as a result of the wearing of masks?

By maintaining the focus on Massai, and by extension the Indians who had not yet been fully integrated into an ever encroaching civilization, director Robert Aldrich and writer James R Webb also keep the focus on the overriding sense of urgency, of time running out. Massai admits to his woman at one point that he is aware of the fact he has perhaps only a few years at best ahead of him, that civilization and his consequent demise will catch up with him some day. And this is where the real urgency resides, the need he soon feels to lay some kind of lasting foundation, to provide some sense of continuity. In narrative terms, this is clearly indicated by the planting of seeds in the earth to grow corn, the idea introduced by the old Cherokee, tested unsuccessfully at first by Massai himself, and then encouraged and brought to full fruition by Nalinle. This notion of growth, of building a future out of nature itself is further highlighted by Nalinle’s pregnancy and the direction in which that development pushes the story. The “some day” Massai foresees arrives at the end. The climactic scene with John McIntire’s Al Sieber crawling through the undergrowth of the cornfield as he stalks the wounded warrior provides a visual metaphor for the creeping advance of civilization, threatening not only Massai’s last Apache, but the future he has tried to cultivate too. Still, the ending is one that is suffused with both hope and a hint of reconciliation.

Aldrich himself claimed not to have wanted to finish the movie in this way, preferring the more negative ending that was laid out in the novel Bronco Apache by Paul Wellman that formed the basis for the script. Some may see that as further evidence of the commonly held belief that Aldrich was first and foremost a cynic, but I’m not so sure. Perhaps that bleakness that could shine through some of his films on occasion was more prominent, rawer in some way, in his early efforts. Even if that is the case, I remain unconvinced that this should be seen as his defining characteristic. There are plenty of examples sprinkled through his work of him displaying if not a completely positive outlook then at least one which sees the better side of humanity in the ascendancy. I’m thinking here of Autumn Leaves, Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte, The Flight of the Phoenix and The Last Sunset, the latter being a movie I’m happy to admit I have come to reassess after being encouraged to give it another go. I recall a commenter on this site once referring to a certain writer as being in “the truth business”, even if I don’t now remember who was being so lauded. Anyway, that’s all by the by. The point is that the phrase stuck with me as it seems that it’s surely the goal of every artist to mine the truth. As such, it feels misguided to regard Aldrich merely as a cynic, as some critics would support, rather than a genuinely rounded artist in the sense that he too was a seeker after truth.

So, without deliberately spoiling matters for anyone yet to view it, I like the way the movie ends. It feels appropriate in that it validates the points made, the struggles endured and the promises alluded to throughout its running time. All that urgency that preceded it, the crowded, pressing framing frequently employed to create the sensation of a cramped and restricted set of circumstances eases. The simple yet instantly recognizable sound of a future long awaited calls a halt to what threatened to be impending tragedy and the “some day” that had loomed large is banished, to be replaced by the chance of a better day. In short, it’s a fine way to bring the story to a close.