Revenge, or at least the quest for justice, is a theme frequently featured in westerns. Relentless duplicity, on the other hand, is more often to be found in crime movies. Ride Clear of Diablo (1953) is a pretty good example of a conventional western that blends both of the aforementioned elements into its brief running time. By using the revenge motif mainly as a device to drive the narrative, rather than indulging in any especially deep analysis, and thus keeping the focus firmly on the various double-crosses, the film manages to provide plenty of exciting, pacy entertainment.

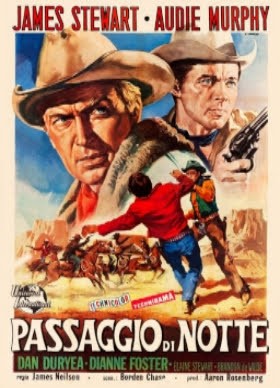

Everything revolves around Clay O’Mara (Audie Murphy), a railroad surveyor based in Denver, who receives a wire informing him of the murder of his father and brother as a result of a raid on their ranch by rustlers. Returning home to bury his family, O’Mara is cautioned against seeking retribution by the local preacher (Denver Pyle), and reassures the man of the cloth by letting him know he’s interested in a meeting with the sheriff. What O’Mara doesn’t know, but we the viewers do from the opening moments, is that Sheriff Kenyon (Paul Birch) and the family lawyer, Tom Meredith (William Pullen), are the men responsible for the murder. Meredith is clearly the brains of the outfit, and he’s the one who advises Kenyon to accede to O’Mara’s wishes and swear him in as a deputy with a view to tracking down the killers. Meredith’s idea is to set O’Mara on a false trail and send him off in pursuit of a man who he figures will gun him down. To that end, Meredith and Kenyon tell him that notorious wanted outlaw Whitey Kincade (Dan Duryea) is one of the leading suspects. O’Mara sets off for the neighboring town of Diablo where Kincade is believed to be hiding out. This is just the first in a series of crosses and double-crosses fill the movie, and none of them seem to work out quite the way any of the conspirators hope. While slightly unnerved, O’Mara isn’t the kind of man to back down from a challenge, particularly not one in which he has as much personally invested as this. As it turns out, he’s no slouch with a gun either and, to the surprise and near mortification of Kenyon and Meredith, manages to outdraw Kincade and haul him back to town for trial. That O’Mara should pull off such a coup is bad enough as far as the villains are concerned, but what’s more troublesome is the fact Kincade has taken a shine to the gutsy deputy. Kincade has his own suspicions regarding the motives of these outwardly law-abiding citizens, but he’s no saint and also has a perverse sense of humor. Rather than put O’Mara on the right track straight away, Kincade toys with him and offers only oblique hints, preferring to sit back and watch pleasurably as Meredith and Kenyon fail time and again to ensnare O’Mara. However, such games can only be played out so far, and O’Mara must sooner or later come upon the truth, while Kincade must also make a decision as to where he really stands.

Director Jesse Hibbs spent many years working in the second unit, and had a relatively short career in charge of feature films before moving into television. Ride Clear of Diablo was one of his earliest directorial efforts, and his first with Audie Murphy – both men would work together a number of times in the years to come. Stylistically, this movie is fairly unremarkable, although there are some extremely atmospheric scenes such as the opening in a near deserted saloon, where an alluring singer (Abbe Lane) ensures a couple of hapless cowboys remain distracted while her rustler friends slip away to round-up the herd. Even though some of the action was filmed on location around Lone Pine, Hibbs arguably does his best work during the interior scenes – which seems a little odd for a western director. The first appearance of Dan Duryea, after his character has been given a strong build-up, and Murphy’s subsequent face-off with him is also particularly well realized. Despite what the events that take place at the beginning may suggest, Ride Clear of Diablo lacks the kind of psychological complexity that is often found in revenge/quest westerns. Still, that shouldn’t be taken as a criticism of the movie as a whole; it never intends to go down that route, and achieves what it wants perfectly well without doing so.

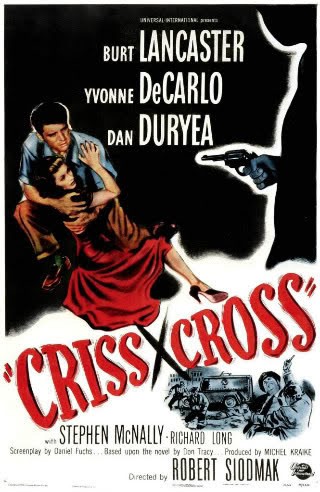

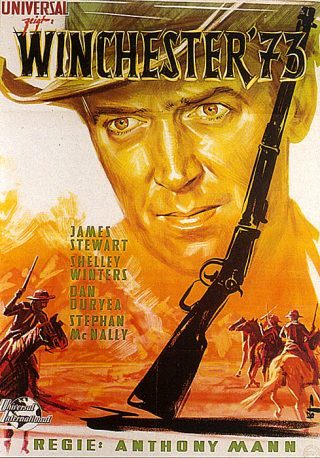

I imagine synopsis I included makes it clear that Dan Duryea’s role as Whitey Kincade makes a significant contribution to the film. I’d go so far as to say that although Audie Murphy receives top billing and gets the lion’s share of the screen time, it’s as much Duryea’s picture as anyone’s. Duryea was one of the finest screen villains ever, even better when he was given the opportunity to play up the character’s ambiguity. With Whitey Kincade he was handed the chance to portray an extremely engaging anti-heroic figure. Duryea always had an enormous amount of charm and could never be characterized as unlikable. Ride Clear of Diablo highlights his playful menace, and he steals every scene he appears in. By the end of the movie your greatest regret is the fact he wasn’t allowed more time to cast his skewed, cynically amused glance over proceedings. In contrast, Murphy is far more stoic and traditionally heroic, and it creates a nice balance. However, even in a pretty straight and limited part such as this, Murphy brought some of that nervy unease, a kind of edgy watchfulness, that made him an interesting lead on so many occasions. Susan Cabot was cast as Murphy’s love interest and, to make matters more intriguing, the niece of the corrupt sheriff. She handled the conflicted aspects of her role well and her presence is both an attractive and important element in the story. Abbe Lane’s saloon girl is equally enjoyable, despite her part offering less depth and impact. The remainder of the supporting cast – Jack Elam, Paul Birch, Russell Johnson and William Pullen – constitute a fine bunch of out and out villains and fall guys.

Ride Clear of Diablo is now available on DVD fairly widely. There have been various European options for some time and the movie was then released in the US, initially as part of a four movie set of Audie Murphy westerns and then later as an individual DVD-R. I have the German version that came out via Koch Media some years ago. The transfer on that disc is a little variable, but satisfactory overall. For the most part it’s sharp enough but there are instances where it briefly takes on a soft, dupey appearance. The technicolor is well reproduced and print damage, despite what looks like an obvious lack of restoration, is limited. The soundtrack offers a choice of the original English or a German dub – there are no subtitles at all. Extra features on the disc consist of the trailer and a gallery, along with liner notes in German. I consider the film to be a very entertaining outing for Audie Murphy and it ought to satisfy his fans. The icing on the cake though is the marvelous performance by Dan Duryea – anyone who has yet to discover the man could hardly ask for a better introduction, and those already familiar with him will have a ball renewing their acquaintance.