I know everyone won’t agree but I’ve always felt that film noir works well in a gothic setting, where the atmosphere is necessarily thick and crimes (particularly crimes of passion) are a basic ingredient. In addition, the social constraints that govern the characters’ lives and actions help to increase the feeling of pressure, while the ornately forbidding homes where many such stories are played out can be just as menacing in their own way as any rain-slicked urban sidewalk. I think the fact that noir isn’t a real genre is one of its great strengths; this lends it a flexibility allowing theme, mood and look to assume as much importance as time and place. Fritz Lang’s House by the River (1950), dripping in heavy gothic atmosphere, confined for the most part to the titular house, and exploiting the suffocating moral code of its period setting, is most definitely film noir. It’s an interesting and at times visually striking work, but not an entirely successful one. However, I’ll go into the reasons for that later.

Stephen Byrne (Louis Hayward) is a writer, but not an especially successful one. He is first seen seated outside his riverside home and working on a manuscript. When a neighbour comments on a foul animal carcass that the current has been carrying up and down the waterway for days, he remarks that it’s a similar story with his writing – his publisher keeps returning it. Despite the light tone of these comments, the river, and its tendency to return anything tossed into it, plays a significant (and even vaguely supernatural) part in the plot. While his professional shortcomings only serve to hint at a weakness in Stephen’s character, the sly, lustful glances he steals at his attractive housemaid make that flaw obvious. Taking advantage of his wife’s absence, he decides to try his hand at seducing the help. However, his inadequacies manifest themselves again and he botches the attempt. What’s worse is that in an effort to prevent the girl’s cries from alerting the neighbours to his philandering, he accidentally strangles her. These early scenes inside the opulent yet oppressive home, all carved furniture and flock wallpaper, are particularly well staged and shot; the extreme angles and the high contrast photography conveying a sense of claustrophobic menace and terror. Having his brother John (Lee Bowman) stumble on the killing might appear to be just one more calamity to befall this man. Nevertheless, it turns out to be something of a godsend. John, with his stiff leg and retiring manner, is the polar opposite of Stephen, a kind and considerate man whose sense of civic duty is only exceeded by his loyalty to his brother. So, when Stephen begs for his help in covering up what he claims was merely a tragic miscalculation, John agrees to bail him out. With the body of the unfortunate servant bundled into an old wood sack, the two brothers row out on the river at night and dump the evidence. But it’s from this point on that the story begins to twist and turn like the meandering river and continues to do so until the literal and metaphorical tide brings everything back home. As events unfold, the contrasting characters of the two brothers are thrown into sharp relief, John’s stoicism and honour growing as the crisis deepens while Stephen’s venal and deceitful nature gradually consumes him.

Fritz Lang’s films, by his own admission, all deal with human weakness and the criminal actions that follow. House by the River can be viewed as a meditation on moral weakness and its corrosive effects; murder, the destruction of family relationships, and the final descent into madness. The small central cast and Lang’s moody visuals ensure that the tension is never relaxed yet the film doesn’t quite satisfy. When this happens the finger of blame can often be pointed at the writing or direction. However, that’s not the case here; I can’t fault Lang’s work and the story is logical enough in context, although it has to be said the ending is both abrupt and a little too contrived for my liking. No, the problem as I see it is more of focus and characterization. It’s important for any film to have a lead who’s capable of stirring at least some sympathy or sense of identification with the audience. In House by the River the lead is Louis Hayward’s Stephen, and he is such a vile excuse for a man that it’s quite impossible to empathize in any way. In the comments on an earlier post I mentioned that Louis Hayward has never been a favourite of mine, but that’s not the issue. In all honesty, his playing of Stephen is a good piece of work – he really fleshes out the smarmy, snivelling aspect of the man. As I said, it’s a matter of focus; the story is seen primarily from Stephen’s perspective, and it’s more and more difficult as the film progresses to feel anything other than revulsion at the self-serving way he latches onto every opportunity to gain advantage at the expense of those around him. The only “hero” of the piece, although I’m not sure the word’s entirely appropriate, is Lee Bowman’s John. Even if there’s arguably too much of the martyr about him, he does present a human face, a kind of moral compass amid the depravity. However, John’s suffering at the hands of his brother is pushed for the most part to the background, and although we’re rooting for him it’s Stephen’s scheming that remains front and centre. I ought to mention Jane Wyatt’s role as Stephen’s wife as it’s the only other significant part. She does tap into a sort of soulful and vaguely bewildered vibe, but this is essentially a two-man show and she is mainly left to play the puzzled dupe before transforming into the typical damsel in distress.

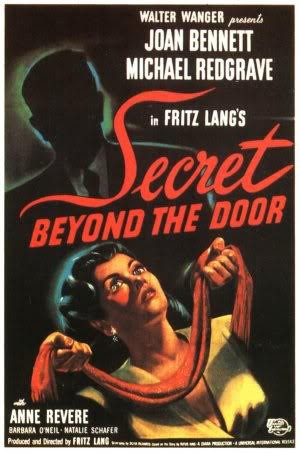

Over the years I’ve bought House by the River three times on DVD before finding a copy that I consider acceptable. The US edition from Kino is a weak interlaced transfer while the French disc boasts a far stronger image but has forced subtitles that can’t be switched off easily. However, last year’s release by Sinister Films in Italy is an excellent alternative, looking as though it’s been taken from the same source as the French version. The film has been transferred progressively and the image is sharp and detailed with only very minor print damage. The Italian subtitles are optional and can be turned off via the setup menu. By way of extras, the disc also features a conversation between Lang and William Friedkin focusing on the director’s time in Germany and lasts around 45 minutes – a most welcome addition. There’s also an inlay card that folds out into a miniature reproduction of the original poster art. All in all, this is a movie that I’m quite fond of – I’ve highlighted the reasons why I don’t see it as one of Lang’s best efforts, but there’s still a lot to enjoy and admire. For those who don’t yet have the film, or others dissatisfied with the editions they already own, I recommend checking out the Italian disc.