Cornell Woolrich was the king of nightmare noir, his fables of fate and downright rotten luck, where everything than can go wrong does go wrong, follow his hapless characters on a perpetual downward spiral. The accompanying sense of dread and doom makes for first rate film noir and a fair number of his novels and stories have been adapted for the screen over the years. I’ve featured a few on this site:

Recently, I found myself viewing a handful of other screen versions of his work and thought I’d just post a few brief comments on them rather than full scale write-ups of the individual titles.

The Guilty (1947)

Jack Wrather was an oilman who decided to try his hand at producing films. While working on The Guilty he met and then married the leading lady Bonita Granville, a former child star who had drifted into B movies. She played identical twins in The Guilty, one of whom is a good girl while the other is most certainly not. The lead was taken by Don Castle, an old friend of Wrather’s whose career didn’t seem to be going anywhere after he’d returned from WWII service. Castle had what I’d term an effective noir persona, a slightly weary charm that felt as though it were only a step or two ahead of desperation. Granville is good enough in her dual role, and the ever reliable Regis Toomey makes for a credible cop. Director John Reinhardt makes the most of the budget and flashback heavy story, wrapping the whole thing up in little over an hour.

I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948)

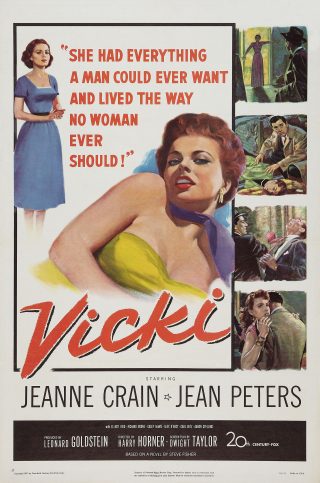

A year later both Castle and Toomey would appear together again in this adaptation, scripted by Steve Fisher and directed by William Nigh, for Monogram Pictures. The flashback technique features once more in this doom-laden tale that opens in the death house with Castle portraying another lucked out type, a dancer who can’t seem to catch a break. He spends his last few hours before that last lonely walk thinking back over how he got where he is. Meanwhile, on the outside his wife lurches between hope and despair as she tries to use what time is left to prove his innocence. Cats, shoes and obsessive love all figure strongly in a satisfying little movie.

Street of Chance (1942)

This movie opens with the main character getting clobbered by some debris falling from a building site. He’s not badly hurt but he does black out temporarily and subsequently discovers he’s not the man he thought he was. In brief, he’s suffering from amnesia and has been living a double life with two very different women, Claire Trevor and Louise Platt. In itself, this is hardly an ideal situation but it takes on that nightmare quality characteristic of Woolrich stories when he comes to realize he’s a wanted man, hiding out and on the run for a murder he has no recollection of committing. This is a strong premise (adapted from the novel The Black Curtain) and directed by Jack Hively, a man who called the shots with George Sanders as The Saint on a number of occasions. Amnesia generally makes for an intriguing basis for noir and typically offers up lots of possibilities for drama and tension. Any picture with Claire Trevor is usually worthwhile too so the ingredients are undeniably promising. Overall, this is an enjoyable film although I have to say I don’t believe Burgess Meredith was leading man material – while I enjoy his work in character parts, I find he’s too quirky and frankly strange to be the lead. This same story was adapted again for television as part of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour and directed by Sydney Pollack. That version had Richard Basehart in the lead, another figure with strong noir credentials and I think he’s actually a better fit for the role.

There was a time when it was practically impossible to see these movies, and the thought of being able to do so in good quality was almost the stuff of fantasy. However, thanks to the efforts of Flicker Alley, Warner Brothers and Kino respectively all of them can now be enjoyed with excellent transfers. None of them could be classed as major films, but they are all very enjoyable and entertaining detours into the world of Woolrich.