“Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.”

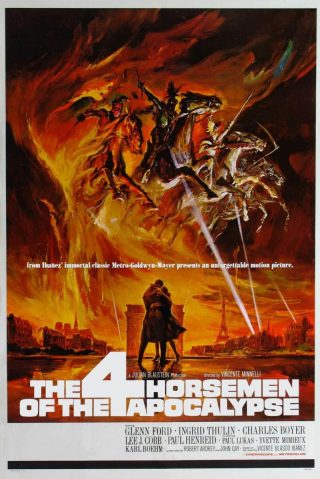

Those lines, the final two of Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem Requiem, introduce the movie featured today. The image of the hunter has long been a romantic one. In mythology Orion was not only renowned for his skills as a huntsman but also for his amorous exploits – in addition to his attractiveness, it is said that he fathered up to fifty offspring by as many different mothers. It is therefore apt that the protagonist in Vincente Minnelli’s Home from the Hill (1960) should also embody these characteristics. And as this hunter moves inexorably towards that repose alluded to in Stevenson’s short poem those features are repeatedly highlighted. In telling this story, Minnelli creates one of his grand melodramas, assembling from constituent parts which are at once discrete and also united in their focus on the deceptions that people lock themselves into in their quest to achieve contentment. How is that to be achieved? Through three interdependent actions: confronting the past, acknowledging the present, and securing the future.

Small town America, the ultimate paradox in some ways, that curious blend of the idyllic and the deeply unattractive. There is something comforting, reassuring, even downright alluring about the sense of orderliness and stability that small, close-knit communities seem to exude. There is a security attached to everybody knowing everybody else, but of course the flip side of that is the preponderance of gossip, of long memories of a malicious type, a type which fosters and breeds grudges. Wade Hunnicutt (Robert Mitchum) is the town’s leading citizen – everybody calls him Captain, adding another layer of deference – wealthy, influential, a noted sportsman, and an infamous womanizer. The opening scene among the bulrushes in the middle of a duck shoot cements all these qualities, the latter one in particular being driven home with some force when Wade finds himself marked as prey by a desperate and indignant husband who has been wearing the horns of a cuckold. That Wade narrowly evades death at his hands is down to the sharp reactions of Rafe Copley (George Peppard) in knocking him just out of harm’s way at the critical moment. By and by, it becomes apparent that Rafe is his illegitimate son, a fact which irreparably soured his marriage to Hannah (Eleanor Parker) and led to her forbidding him to have any involvement in the raising of Theron (George Hamilton), their son who was born in wedlock. That all changes though when Wade comes to realize Theron has reached an age where he needs to learn some lessons that will see him graduate to manhood.

Manhood, however, entails a good deal more than being adept at hunting and the use of firearms, the sowing of wild oats, or even the kind of rugged individualism that Wade Hunnicutt espouses. Those are mere trappings, the panoply of masculinity that one may or may not need to adopt in certain situations, but the characteristics of a man are more nuanced, they run deeper and ask more of the individual than that. This of course forms the core of the movie, the processes, experiences and trials that one must pass through and absorb on the road that leads a boy to grow into a man. That road may be circuitous, forked, ill-defined or uncharted depending on the person who treads it and the destination won’t be the same for everyone yet it’s a journey none can avoid. Maybe more than anything it is the bumps and hollows encountered, and how they are navigated, that ultimately mark the man. For better or worse Wade Hunnicutt has grown into the man he is, and the meat of the tale is to be found in the trajectories followed by Rafe and Theron. The former moving through the roles of tutor, guide and confessor, creating an illusion of being the finished article while he’s really still only part way along on life’s learning curve. Theron is starting further back, having been cocooned in the cotton wool of innocence, his path to maturity seems more dramatic and raw as a consequence. His growing awareness of his father’s legacy, the galling revelations this exposes with regard to the family he thought he knew, and his rejection of a potentially redeeming love see him cast out, his full maturity if not denied then at least deferred.

There is a degree of mirroring with regard to the behavior of the characters. Theron’s disgust at the hypocrisy he discovers at the heart of his family drives him away. He has already proved his physical courage in the wild boar hunt and then his loss of innocence sees him strike out alone seeking independence from his parents and thus indirectly fulfilling another of his father’s wishes. Still, his immaturity and callowness lingers and he ends up, through fear of both himself and his family’s history, abandoning storekeeper’s daughter Libby (Luana Patten), who he has left pregnant. Despite himself, he has acted as his own father did with Rafe’s mother. While Theron is fated to recycle the sins of the father, Rafe is afforded the opportunity to forestall some of the prejudice and rejection he suffered. The past throws long shadows though, especially in these small towns, and even the best intentions can be ambushed by small minded parochialism. Rafe’s selflessness and essential good nature is undermined by cheap gossip and leads to yet more tragedy, though perhaps one whose foundations had been laid long before.

The screenplay for Home from the Hill came via Harriet Frank Jr and Irving Ravetch, adapting a novel by William Humphrey. The writing couple had come off two tricky William Faulkner adaptations directed by Martin Ritt, the rather fine The Long, Hot Summer and the less good but still worthwhile The Sound and the Fury. Now I’ve not read Humphrey’s novel but a quick bit of research suggests the screenplay made a number of changes to the story and characters, and I think the original tale must have been quite different as a consequence. What we get though forms the basis of a fine melodrama, the type of material that was ideally suited to Minnelli’s talents and vision. Perhaps it is a touch more subdued than some of his other melodramas, the palette chosen reflecting this to some extent. There is an earthiness on display in the soft green and brown hues which predominate. However, there are flashes of those vivid shades often found in Minnelli’s pictures at key moments – the crimson dress worn by Luana Patten in the waterside scene where she entrances Theron, the rich burgundy upholstery in Wade’s den where the affairs of men are raised and settled, and then the blood red tombstone in the final scene that is somehow triumphant, sedate and reassuring all at once. These are all instances of great passion and those varied tones of red capture the mood of the scenes perfectly. It’s noteworthy too that the site of Theron’s climactic revenge is backed by an acrid yellow, the noxious gases rising off the swamp matching the bitterness on show.

Robert Mitchum catches all the shades of his character, the arrogance born of privilege often to the fore and, in his more private moments, a hint of humility creeping through whenever he’s reminded of his personal failings. The scene which offered him the most to work with occurs during the barbecue arranged in the wake of the boar hunt. Sharing the screen with a pensive Eleanor Parker, both of them are on the porch overlooking the revelers on the front lawn. Mitchum starts out gently, reminiscing and quietly romancing the woman who has spurned him for so long. He seems to be making headway, gradually softening her with his talk of bygone and better days. And then just as he seems to have victory in sight, she slams the door, telling him in no uncertain terms that he’ll never have her. The wounded pride and the hurt of rejection, that sudden, sour realization that it’s all been for nothing flash across Mitchum’s features for no more than an instant yet he accomplishes it all so effortlessly. Fine acting.

Eleanor Parker is all frozen dignity and has a hugely influential role, her character’s actions motivating and coloring the lives of those around her. The strained marriage to Mitchum has led to her overprotecting her son and the decay that characterizes that union ends up blighting the latter’s life. George Hamilton gets the sullen immaturity of Theron across quite successfully and Minnelli would use him again, albeit less satisfactorily, in Two Weeks in Another Town a couple of years later. George Peppard, in just his third feature role, is excellent as Rafe. His character may have been denied a name and left unacknowledged but he carries himself more easily than Theron. While there is resentment inside, he covers it with a veneer of assurance and gets to play some of the most memorable scenes in the picture: the interlude in the cabin with Theron after the truth of his identity has been brought out into the open, his stepping up to the plate with the distraught and desperate Libby, and his tenderness after the marriage. The film is all about the attainment of manhood and the contentment that this brings and Rafe’s progression towards that goal is an immensely satisfying one to follow. Theron only gets to take the first faltering steps before being sidetracked by upheaval, but Rafe reaches his destination and gets there in some style.

The movie features two cemetery scenes and I guess there is some quality about that spot none of us can avoid which draws forth honesty and strips away the pretense. Both scenes involve Peppard and Parker, the first is wistful and touching as Rafe carefully tends the plot on “reprobate’s field” where his mother reposes. He’s come to terms with his regrets and there is a sense of a young man who has made his peace with who he is and his place in the world, while Hannah sees the beginnings of a thaw warming her heart. It’s all very understated and very effective. Then reminiscent of the final glorious scene in Some Came Running, Home From the Hill draws to a close in another cemetery. All at once memories and loss shed their sorrow, fusing instead into something rich and positive. The point where we witness resentment chase briefly across Rafe’s face before being banished permanently leads to a moment of catharsis and truth, the healing of a wound long suffered by both himself and Hannah achieved through an instance of shared decency and unity. A homecoming lent greater significance and value by being so hard-earned.

Perhaps I’ve rambled on a little too much about this movie, but it’s one I have always admired and it has stuck with me since I first caught a broadcast on TV by chance some forty years ago. It’s a strong addition to that wonderful run of melodramas that Minnelli embarked on in the 1950s and the early 1960s. I have spent a fair bit of time here on some of the performances and a handful of key scenes, but I’d also like to take the opportunity to mention the score by Bronislau Kaper. It is a marvelously evocative piece of work, those lush soaring strings backed by melancholic horns, plaintive as a hunter wearied by the chase. I’d just like to sign off on this piece with his main title theme to the movie.