By the 1960s film noir had had its day, at least that’s what the critical consensus tells us. Anything after that gets variously referred to as post-noir, neo-noir etc. I don’t know, age has made me less interested in labels and I find myself paying only scant attention to them these days; they are useful for marketing purposes and the like, but I’m not selling anything. So, all of that is just in the nature of a disclaimer lest anyone should object to my hanging the tag film noir on Man-Trap (1961) – I did so because the subject matter, resolution, personnel and general feel pointed in that direction for me.

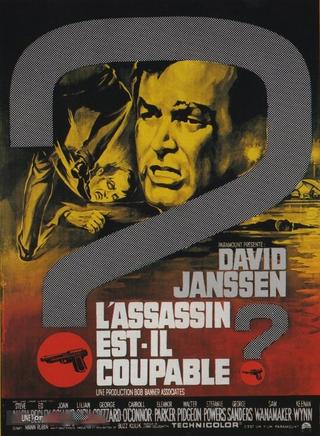

There’s a brief opening section, a prologue of sorts, which takes us back to 1952 and Korea. The purpose is to establish some facts that will influence the story to be told. We learn that Matt Jameson (Jeffrey Hunter) is a decorated war hero who got a medal pinned to his tunic and another piece of metal inserted in his skull while saving the life of his comrade in arms Vince Biskay (David Janssen). Years pass and Matt is trapped in an unsatisfying job and a marriage to the boss’ daughter Nina (Stella Stevens) that is even more toxic. He’s essentially been consigned to a suburban hell, an American nightmare of disillusionment and disenchantment. So, when Vince turns up, apparently out of the blue, brimming with roguish charm and a business proposition, Matt is moderately receptive to say the least. Vince has been hiring his services out to the highest bidder in Central America and in so doing has hit on a scheme to profit from political unrest and bag a cool $3 million dollars. As Matt’s relationship with the alcoholic and promiscuous Nina deteriorates, his desire for his secretary as well as the promise of full financial independence drives him to fall in with Vince’s scheme. All of this leads to a botched heist and a radical change of plan as the law, hitmen and domestic discord all begin to apply pressure.

Man-Trap is full up of the kind of bad choices, ill fortune and empty opportunities that characterize film noir. Perhaps it doesn’t have the classic look, but that arguably evolved over time anyway and the slightly flat, TV movie appearance of the visuals is not entirely out of keeping with other late era offerings. Aside from a couple of television shows, this was only Edmond O’Brien’s second feature as director after his collaboration with Howard W Koch on Shield for Murder. It’s only a partially successful effort though, the low budget is always noticeable and the script isn’t all it could be. On the plus side, the heist sequence and its aftermath through the streets of San Francisco is well filmed and quite exciting. O’Brien manages to fit in some imaginatively framed shots here and there, but the writing remains problematic – the screenplay is an adaptation of a John D MacDonald (Cape Fear) story, which maybe creates unrealistically high expectations. The high point is the heist and the momentum is never regained after it takes place. That wouldn’t have to be a problem if the film wound up faster, but there’s still a whole lot of storytelling to get through before the credits roll.

I also get the impression that either O’Brien or the screenwriter Ed Waters wanted to make the movie a critique of the state of middle class America as much as a thriller, but ended up with those elements orphaned and only partially addressed. Matt and Nina’s rotten marriage feeds into this but it’s the portrayal of the appalling neighbors which hammers it home. This suburban degeneracy is peopled by a gallery of grotesques, sad swingers who spend their time boozing, leering and gossiping. It’s a snapshot of the moral decay simmering below the surface of the backyard barbecues. Maybe it’s the presence of Jeffrey Hunter that had me thinking how it was vaguely reminiscent of aspects of Martin Ritt’s No Down Payment, though that is a far superior movie on every level and indeed almost like a Douglas Sirk film with the varnish scraped off. Man-Trap can’t aspire to that and although these aspects are diverting enough, I feel it might have worked better all round had it avoided them and kept its focus tighter.

As for the acting, Jeffrey Hunter does reasonably well as the dissatisfied Matt, uncomfortable and unsettled for much of the running time, but the developments in the latter stages of the movie don’t succeed. Everything takes a detour into the type of ill-starred territory one would associate with a Cornell Woolrich tale yet it lacks the suspense that give such fatalistic fables their teeth. David Janssen, however, is excellent throughout. He nails the charm and duplicity that define the character of Vince, beguiling and bedeviling just about everyone he comes into contact with. On the other hand, the real weak link for me was Stella Stevens. She does well in the early scenes where her coquetry is to the fore, but the more her angst and desperation grow, the less convincing she becomes. In the end, it feels like a very transparent performance and it hurts the film as a result.

Man-Trap was a Paramount production and got a release in the US via Olive Films some years ago. That was a solid transfer, crisp and attractive in the way black and white ‘Scope movies tend to be. Olive are now defunct of course so I’m not sure how readily available the film is these days. All told, it’s a picture that works in places – Janssen’s characterization, the heist – but falls down due to scripting issues and some unsatisfactory work from the leading lady.