Maybe I should have been an engineer. Or perhaps not. Bridges and links and halfway houses in all their forms hold a fascination for me, just not in the structural sense. If you watch enough movies, patterns emerge and it’s difficult not to think in terms of eras and their associated styles. The western continues to draw me and over the years I’ve developed a deep affection, one might even say a love of the variety that came to fruition during the 1950s. Of course no genre reaches maturity suddenly or spontaneously, nor does it do so in a uniform fashion. It’s a gradual process and a fluid one, advancing and retreating from movie to movie and this is even discernible within individual movies themselves. I think that it was somewhere in the late 1940s, when that post-war sensibility had begun to make itself felt across a whole range of genres, that the western really found its feet. However, the preceding years hint at some of the bridge building that was underway, and a film such as Tall in the Saddle (1944) is of interest in that respect. There is a distinct flavor of the breezier 1930s western to parts of it, and also a hint of what would develop in the years ahead, that latter aspect possibly making itself felt as much in the visuals as anything else. And then there is the evolution of the screen persona of John Wayne to be considered.

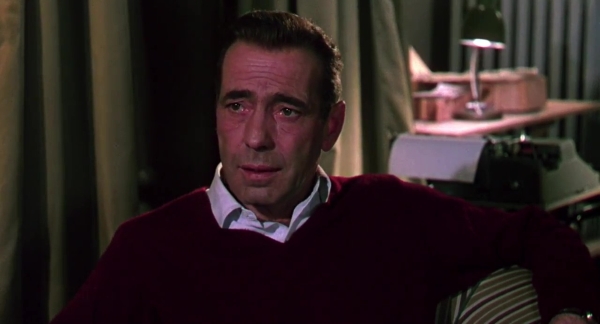

A mystery of one type or another is typically an attractive hook upon which to hang a story and a lead who is himself introduced as something of a mysterious figure is even better. Rocklin (John Wayne) is just that, a man with a surname and nothing more, hitching a ride on a stagecoach and on his way to start afresh. Bit by bit, a little more is revealed about him, but only very gradually and only that which it’s necessary for the viewer to know. This is very much in keeping with the western tradition, a figure striking out towards new frontiers, an identity defined by his actions and behavior in the present rather than any preoccupation with a past that is of no consequence. In a sense, Rocklin (and by extension the man playing him) is a representation of the West, resourceful and independent, forward-looking and unsullied by pettiness or corruption. He seems to fit right in with the ruggedness of his surroundings, simultaneously aware of the dangers and risks yet not intimidated by them. That his journey west has a purpose is never in doubt, but this is slowly revealed and only fully brought to light at the end of the picture. As we go along it’s enough for the viewer to be aware that Rocklin has been deprived of something that he had expected to find, and that he’ll not rest till he finds out who is responsible for this. The man he thought he’d be meeting has been killed and he’s now been cast adrift, the work he thought he’d be doing is no longer so appealing so he ends up accepting a job as foreman for the tomboyish Arly Harolday (Ella Raines). I don’t want to go into too many plot details here – it’s a fairly convoluted business involving inheritances, land grabs and assorted betrayals – but suffice to say that Rocklin finds himself tangled up in local disputes and as well as one of those romantic triangles where there’s never the slightest doubt how it’s all going to turn out. I guess the point I want to make here is that the tale itself is of less interest or importance than the way it’s told and the people who are involved in the telling.

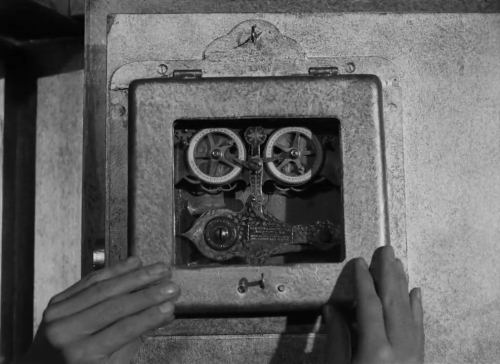

Edwin L Marin’s credits as director stretched back to the 1930s, but I think Tall in the Saddle marked the beginning of the more interesting phase of his career, one that would be curtailed by his untimely death in 1951. From this point on he would make a series of entertaining westerns with Randolph Scott, as well as a number of crime pictures with George Raft. None of these would be considered classics or anything but they are good movies overall. The script here (by Paul Fix, who also has a memorably sly supporting role) is arguably too busy, albeit with a few good lines, but Marin keeps it all moving along so that it never gets bogged down in the kind of intricacies that aren’t all that engaging. Surprisingly for a western, the interiors are more visually pleasing than the exteriors, which is probably due to the work of cinematographer Robert De Grasse, a man who filmed a string of fine genre pictures in the mid to late 1940s, such as The Body Snatcher, The Clay Pigeon, Follow Me Quietly, Crack-Up and The Window.

As I mentioned above, Tall in the Saddle comes across as something of a bridging exercise now, not least for the the way it slots into John Wayne’s career path. Both John Ford and Raoul Walsh had begun the process of molding that iconic image, but it would be the late 1940s before his full potential was realized. Still, Wayne’s growing confidence on screen was apparent here – his handling of himself in the action scenes, especially his confrontation of a hapless Russell Wade and the determined way he faces down and pistol whips Harry Woods, is exemplary. What’s more, there is a real spark between Wayne and Ella Raines, her spitfire allure demonstrating how well he responded to being paired off with leading ladies who were capable of giving as good as they got. Ward Bond provides good value too in one of those oily parts he excelled at. Audrey Long is an attractive if slightly ineffectual presence as the other side of the love triangle involving Wayne and Raines. In support Gabby Hayes is his usual self – personally, his shtick is something I can take or leave depending on my mood, but some will be more tolerant. Other familiar faces on display are Russell Simpson, Frank Puglia and George Chandler. A young Ben Johnson is supposed to be in there somewhere too, but I’ve never been able to spot him.

Tall in the Saddle can’t be classed as a great western, or a great John Wayne movie, but it is quite intriguing as a kind of cinematic pathfinder, strongly influenced by the films that preceded it and looking ahead to the riches the genre would unearth in the years to come as well. It’s also an entertaining and enjoyable watch, all of which makes it a worthwhile viewing experience.