While my previous post arguably brought up the matter of the parameters one applies to the notion of the western, it was a few comments leading on from that which added some impetus and got me thinking a bit more. I guess I have my own idiosyncratic criteria which I wouldn’t expect to satisfy everyone. So be it, but that wasn’t the direction I now found my thoughts running in anyway. What I ended up contemplating was the course that the western as a genre charted after it had peaked in the late 1950s and on into the early 1960s. Reaching a peak means that some form of change is inevitable, but the path the genre adopted led to a sustained decline. That path essentially operated on two levels: one the one hand, there was that slightly desperate and ultimately unsatisfying effort to ape the nihilism at the heart of the spaghetti western, while on the other hand, there grew up a fruitless attempt to cling to the tropes of the classic form, one rendered stale by the crucial absence of thematic richness. Somehow these twin approaches converged at the artistic quagmire that came to be referred to as the revisionist western, where the myth was not merely deconstructed but practically obliterated. Yet what if an entirely different approach had been pursued instead, one which filmmakers had flirted with and dabbled in but failed to fully embrace?

I’m speaking here of what is sometimes called the modern or contemporary western, and I’m also well aware that there will be those who struggle to accept that such movies are “real” westerns at all. While I can’t say I share such reservations, I do understand them. Fairly recently, I happened to revisit a couple of movies that fall into this category, The Lusty Men (1952) and Hud (1963), with a view to maybe writing them up separately. Nevertheless, it now seems apposite to fold them into this piece on what I’ve been toying with for a while now, namely that the western might have been better served in the long run had filmmakers made a clean break and gone a different way. I guess it’s always easy to spot missteps when one has the benefit of hindsight to frame it all, but looking back at so many less than satisfactory westerns that were made from the mid-1960s on does create the impression of people trying to recapture lightning in a bottle. Instead of reaching for the unattainable, I can’t help but wonder if the people making westerns wouldn’t have been better off acknowledging that the way to secure the future of a genre so strongly rooted in the past was to allow it to naturally evolve into a recognizably modern form which still retained something of the spirit that made it great in the first place.

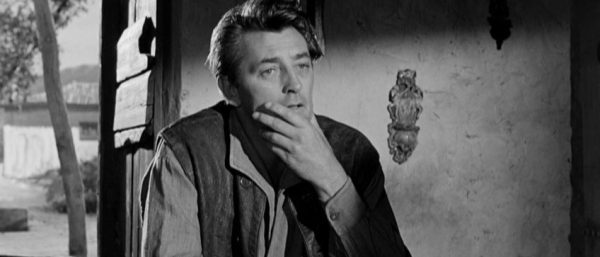

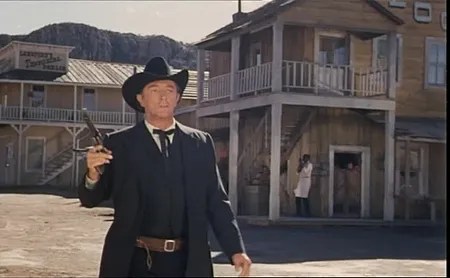

In The Lusty Men Nicholas Ray stirs together the doomed romanticism of Jeff McCloud (Robert Mitchum), a dwindling band of itinerant rodeo performers and one of his characteristically uneasy relationships. From the moment a limping and broken McCloud gazes with the kind of melancholic longing only Mitchum could impart so effortlessly at his childhood home, it’s clear he is meant to represent some bridge between a lost idyll and a world where skills once carefully acquired to tame the land itself are now of use primarily for display and entertainment. Wes Merritt (Arthur Kennedy), his protege, sees this the other way round – that the shows and spectacle may be a way to reconnect with the land. The whole movie traces McCloud’s slow reconciliation with the man he has now become, of the fact the world no longer holds a place for him. It also charts Merritt’s concurrent but bumpy journey back to his origins, aided by the tough earthiness of his wife (Susan Hayward) and by McCloud’s sacrifice. The world of Ray’s The Lusty Men is very much a contemporary one, and never tries to suggest otherwise, but by the time those still standing take stock of the lessons learnt and head back to the land which spawned them they are strengthened by their experience. The viewer too is fortified by the time spent tagging along on their journey, and that’s in no small part down to the way the essence of the classic western is transferred to the mid 20th century setting.

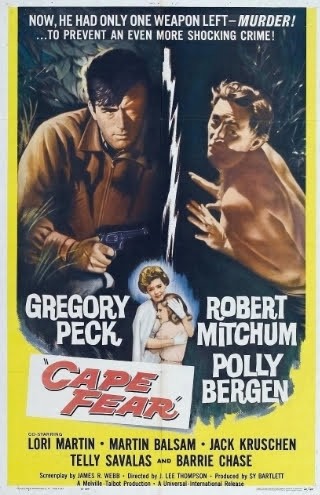

Martin Ritt’s Hud, adapted from a Larry McMurtry novel, came along a decade later and is a darker affair all told. It’s a film about change and passing, about a fractured family dealing with the notion of passing, of guilt and blame and principle. Paul Newman’s titular character is the new face of the west, amoral and self-absorbed, straining against ties to the past as represented by his father (Melvyn Douglas) and casually dismissive of a future hinted at by his nephew Lonnie (Brandon deWilde). Buoyed by two superb Oscar winning performances from Patricia Neal and Douglas, the former touching on a marvelous sense of resignation and regret, while the latter simply exudes pain and dignity, it scratches away at the mythology of the west. The culling of the herd is sobering in its matter of fact coldness, and Douglas’ subsequent putting down of his prized Longhorns, the last of the breed, is deeply symbolic and even more traumatic on a personal level – the hurt of the man is palpable. There is a bleakness to all this, yet the ending also looks to the resilience of the genre. If Hud’s shutting out of the modern world is indicative of a dead-end insularity, then Lonnie’s rejection of his uncle’s negativity and his striking out alone in the world looks toward a different horizon, an approach the genre itself is built upon.

While what I’m going to call ‘regular’ westerns made from the middle of the 1960s onward are very much a mixed bag for me – with far too many misses weighing down the hits – I don’t think I’ve seen a ‘modern’ western that actually disappointed me. The form continues to be made, and quite successfully too if TV shows such as Yellowstone are any kind of guide, but it still feels as though it is only visited from time to time. Admittedly, I’m doing no more than musing and hypothesizing here, spitballing something I’ve not yet reached a conclusion on myself. Increasingly though, I think Hollywood may have missed a trick by not abandoning the traditional western at some point in the late 60s, or at least by the 1970s, and turned the genre away from the static form it devolved into. Had this happened, had it become a contemporary rather than a historical form, perhaps we would be talking about the western in entirely different terms today, as a still thriving genre.