“Civilization is creepin’ up on us…”

There’s a similar sentiment, and indeed similar words, expressed at the start of Raoul Walsh’s The Tall Men. Indeed it could be said that variations on this theme run all through the western genre. Can it be said then that the western is at heart an unfolding elegy? One would certainly be justified in applying that label to many of those movies made in the late 1960s and on into the following decade, what have come to be referred to as revisionist works. Yet the roots of that can be found in the classic era, the golden age of the genre in the 50s, when the spirit of celebration, of hope and redemption, were just beginning to be tinged with a hint of regret at the gradual drift away from an ideal. Even the title of Anthony Mann’s The Last Frontier (1955) catches a flavor of that crossing of the Rubicon. Granting that the notion of the Old West as some pastoral idyll was as much myth as reality, it seems fitting that the process which plays out before the viewer is not framed in terms of tragedy, although there are clearly tragic elements woven into it all, but is instead presented as a natural and perhaps desirable step towards the inevitable.

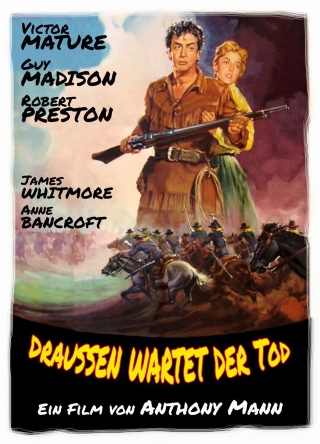

The opening of The Last Frontier presents an image of perfect wilderness, of a land largely untouched by man. Yet we see three men making their through the rocks and trees. This is Jed Cooper (Victor Mature) and his two companions Gus and Mungo (James Whitmore and Pat Hogan), and before long the earth around them seems to take on another form as an encircling band of Sioux rise up from the grass and scrub as though they were children of the soil itself. The thing is both groups, the trappers and the Sioux alike, give the impression of being just another natural extension of their environment. Nevertheless, the trappers are made aware of the fact they have come to represent the intruder, are promptly deprived of their weapons, horses and bearskins and warned to stay clear of the forests. Why? In brief, the arrival of the army and the construction of a fort has altered the way the Sioux now perceive them. Indignant and resigned yet still alive, Cooper makes for the fort in search of some form of compensation for the loss of a year’s worth of hides. What he gets, however, is the offer of employment as a scout under the young acting commander Captain Riordan (Guy Madison). Despite the reservations of his friends, Cooper is beguiled by the thought of a blue tunic with brass buttons and wonders if he might not get to wear one at some point. Thus he begins to fall under the spell of civilization, a feeling further enhanced when he makes the acquaintance (albeit in a drunken and rambunctious state) of Mrs Marston (Anne Bancroft), the wife of the absent senior officer. Colonel Marston (Robert Preston) is at that point on the other side of Red Cloud’s Sioux, which by Cooper’s calculation means he’s probably dead.

As it turns out he’s very much alive and Cooper’s efforts to guide him and what remains of his command back to the safety of the fort earn him little in the way of gratitude. Marston is far from being a well man, psychologically at least. He carries the scars of shame and defeat, haunted by the ghosts of the 1500 souls he led to their graves at Shiloh. The western is full of men in desperate need of redemption, though as often as not the wounds they seek to heal are neither so deep nor so raw as those which afflict Marston. His goal is to excise the pain of defeat through victory over Red Cloud. Unwittingly, Cooper’s growing need to embrace civilization and all he perceives it as offering leaves him pinned at the center of both an emotional and military crisis that Marston is hell bent on engineering. Ultimately, all the elements will be drawn together in a swirling maelstrom of dust and death.

The westerns of Anthony Mann are among the greatest of the classic era. They typically feature driven and obsessive heroes, and of course the concept of redemption is never far from the surface. That sense of redemption, of restoring oneself spiritually, of paying one’s debts and regaining one’s rightful path in life is a powerful one and Mann spent a decade exploring it. In The Last Frontier the character most noticeably driven is Marston, a man who has hounded himself to the brink of sanity and even of humanity. He is not the hero of the piece, though one could say that if he doesn’t quite redeem himself he does get to earn his peace, although it comes at a considerable cost to others. Cooper is the undoubted hero, a crude and unfinished product of nature, one who doesn’t need redemption in the sense of making atonement but rather one who has reached a critical point in life and requires guidance. I guess there’s something ironic in the figure of the pathfinder in the wilderness threshing around at the gates of civilization and needing help to regain his course. Yet that is what happens.

I think that the message of this movie is that no state or situation is to be sought in itself, that the myth of the free and open west is only sustainable and valid if it’s viewed as a stage in a process, an attractive stage in many ways but not a permanent destination. Marston’s relentless drive toward confrontation comes to the only end that it can, and of course history leaves us in no doubt that the staunch resistance to change of Red Cloud was similarly doomed. So what then of the other options? There is a strong feeling that the settler can only go so far till the siren call of civilization drowns out the pull of the untamed land. There is a pivotal moment late on when Mature, having abandoned the fort in the wake of one of those brutal fights so typical of a Mann film, must confront the fact that he can go no further. His journey is going to have to continue along a different path, one which leads back to civilization or whatever form of it he cares to shape for himself. Mungo, the native, is not restrained in the same way and is thus free to proceed on his own trek, one which is expressed in Mann’s characteristic cinematic language as a journey forever upwards, always ascending and always seeking to attain some higher place. Maybe both are heading for the same destination, just taking different routes to get there?

I haven’t given a lot of attention to the performances in this movie, which is a bit of a departure from my usual formula. That’s mainly due to my choosing to focus more on the themes and ideas underpinning the movie, as well as the fact that all of the principals are uniformly excellent. However, I would like to single out some remarkable work from the often maligned Victor Mature – he really gets into the character of the unpolished trapper, investing the part with a passion and raw energy that is wholly convincing as he cannons back and forth between confusion, wonder and enthusiasm. I think it’s a terrific performance. A word too for the cinematography of William C Mellor, where he and Mann fashion a neat juxtaposition of dark and claustrophobic conditions within the (confining, civilizing or both?) walls of the fort and the bright, open airiness of the surrounding landscape. As far as I know, the only Blu-ray release of The Last Frontier is the German edition. It is a good if not great transfer, certainly a step up from the rather indifferent DVD but I must say I’m mystified why this interesting Anthony Mann film remains unreleased in the US or UK with the kind of supplementary material it surely warrants.

As an aside, and for what it’s worth, yesterday marked sixteen years to the day since my first uncertain blog entry.