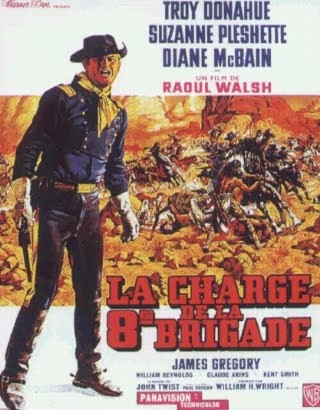

It’s been remarked on before how the 1960s saw a gradual change in approach adopted by the Hollywood western. And it was indeed gradual, up until the middle of the decade, and even a little further in some cases, the influence and sensibilities of the 50s could still be discerned. The change, when it did come, tended to be most marked in the work of the newer breed of directors. The old hands, the pioneers, remained closer to the traditional vision and portrayal of the west. Raoul Walsh, with his earliest directing credit stretching way back to 1913, was most assuredly of the old school, and his final film A Distant Trumpet (1964) has more of the feel of a 50s western than one from the mid-60s.

The film opens spectacularly with a clash between the massed forces of the US cavalry and the Apache. It then cuts swiftly to the academy at West Point where General Quait (James Gregory) is delivering a first hand account of those events to a class of cadets. Among his audience is a young lieutenant Matt Hazard (Troy Donahue), soon to be posted to the remote and undermanned Fort Delivery in Arizona. It’s through Hazard’s idealistic and ambitious eyes that the remainder of the story is seen. The slovenliness, incompetency and insubordination he encounters at the isolated outpost is an affront to the young man’s sense of military propriety. As he assumes the task of whipping the rag-tag detachment into something resembling a modern, disciplined fighting force we get a look at the day-to-day lives of cavalrymen that, in some respects, recalls the work of John Ford. Woven into this is a, not altogether successful, romantic subplot which sees Hazard torn between his betrothed, the General’s niece Laura (Diane McBain), and Kitty (Suzanne Pleshette), the wife of a fellow officer. The second half of the movie sees General Quait and his troops arrive at the fort, and the emphasis shifts to the military campaign to neutralize the threat posed by the renegade Apache War Eagle. Quait’s tactics prove only partially effective however, and achieve not much more than driving War Eagle back across the border into the safety of Mexico. Holed up somewhere deep in the Sierra Madre, War Eagle is at liberty to raid over the border whenever he feels like it. Unless of course someone is prepared to risk his neck going alone into the Apache stronghold to negotiate terms with the old warrior. All told, the latter half of the movie works a lot better, not least because the unsatisfying romance is sidelined for long stretches. Not only are action and spectacle brought to the fore, but there’s greater opportunity to highlight the inherent pro-Indian sympathies of the film.

Raoul Walsh brought a lifetime of experience to the shooting of A Distant Trumpet, and the staging of some of the later battle scenes has an epic quality, aided by the wonderful camerawork of William Clothier. Walsh was always a first class director of action, and location work suited his talents especially well. The wide lens is used very effectively to highlight the vastness of the landscape and, again in a way reminiscent of Ford, the relative insignificance of the tiny humans framed against the primal backdrop. It’s easy to forget though that Walsh had a flair for close-ups and more intimate composition too, and the film offers plenty of chances to sample that aspect of his skill. One of the other great strengths of the production is the score; Max Steiner’s pounding, martial theme adds drive to the film and powers it along. And that brings us to the script, so often the crucial factor when it comes to making or breaking a film. The basis for the movie is a novel by Paul Horgan (not having read it, I can’t comment on how true the adaptation is) and the script derived from this reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of the finished product. To begin with the positives: the story told is in effect an account of the latter stages of General Crook’s campaign against the Apache, and Geronimo in particular. Right away we have both a compelling narrative and, just as important, a chance to cast a critical eye over government/army relations and policy towards the Indians. The script treats the Apache with the greatest respect – not phony sentimentalism or misplaced adulation – and adopts a mature and balanced stance. There’s no shying away from atrocities, nor is there any attempt to gloss over government hypocrisy and the shabbiness of broken promises. One could, I suppose, complain about the positive resolution that doesn’t take into account how events really played out, but overall the film pulls no punches in its portrayal of the situation. As for the negatives, the aforementioned romance, and consequent soapy elements, isn’t very well realized. It would appear to exist primarily as a means of fleshing out the character of Lt Hazard, however, it actually only serves to bog the picture down and dampen the pace in the first half.

I think of Troy Donahue principally as the star of 50s and 60s soap dramas. I understand his performance isn’t all that well regarded in A Distant Trumpet, but I’ll break ranks here and say that he’s reasonable in certain scenes. He fares best in the latter stages where he’s called on to play the action hero for the most part. His deficiencies are far more noticeable in the intimate scenes though, and that makes the romantic stuff seem even more labored. I guess it doesn’t help any that the parts of Suzanne Pleshette and, more especially, Diane McBain are pretty much under written. Pleshette has the stronger, more sympathetic role, while McBain gets to look glamorous but is saddled with playing a stuck-up, unattractive character. To be honest, McBain’s part could have been cut from the movie and not harmed the narrative one iota. James Gregory is very entertaining and seemed to enjoy playing the Latin-quoting general. Every scene he’s in is all the better for his presence. Claude Akins is good value too as the Indian agent, and purveyor of anything and everything from whiskey and guns to loose women. Generally, the supporting cast is fine with small but memorable roles for Kent Smith, Judson Pratt and William Reynolds.

A Distant Trumpet is widely available these days via the Warner Archive and various European releases. I bought the French Warner Brothers DVD back when it was the only edition available. That’s more than a few years ago now but the transfer still stands up well in my opinion. There’s a nice, crisp and colorful anamorphic scope image that’s basically undamaged. French DVDs can be troublesome when it comes to subtitles, but I don’t think I’ve ever had any issues with Warner releases. The subs are easily disabled via the language menu on this one. All in all, the film is what I’d call sporadically successful; there’s a strong story in there with a message that’s subtly expressed and never feels forced. On the other hand, there’s flab in the script too that could and arguably should have been edited out. There’s an ambition to achieve something approaching the epic, but the scripting and some of the casting choices fall short. However, while I have some reservations, I feel the movie works reasonably well on the whole.