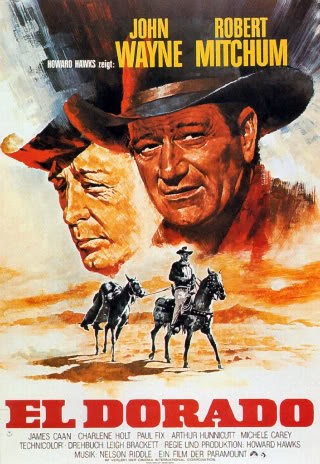

A while back I mentioned directors remaking their own movies, citing Hitchcock and Walsh at the time. However, they’re not the only ones; Howard Hawks reworked the same material that he originally used for Rio Bravo no less than three times. In this case, I think the law of gradually diminishing returns applies – although I’m aware that there are those who might disagree. Hawks’ second trip to the well resulted in El Dorado (1966), a film that improved on its predecessor in one or two ways but ultimately remains a less satisfying work. Ok, it’s not a straight remake of Rio Bravo since it opens the story up a little more in terms of people and locations but it does use the same core situation and characters. There’s the tough professional, the drunk, the old coot and the green kid all holed up in a dingy jailhouse and under siege.

Cole Thornton (John Wayne) is a professional gunman who hires his skills out to the highest bidder. After accepting an invitation from one of the parties involved in a range war he discovers that the job would mean facing off against an old friend. Sheriff J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum) is the lawman caught between the feuding factions, and it’s his presence that dissuades Thornton from signing any contract. However, before Thornton can take his leave an accidental shooting leads to an ambush that results in his getting a bullet lodged perilously close to his spine. When he returns some months later he finds that Harrah has taken to the bottle in the wake of an ill-judged love affair. To make matters worse, the nearly incapacitated sheriff is in no position to cope with the ongoing range war that’s about to come to a head. Therefore, it’s left to Thornton to take charge of a rapidly deteriorating situation provoked by an attempted murder and the subsequent arrest of one of the feud’s main players. Up to this point the plot has its own reasonably unique slant. However, once Thornton, Harrah et al find themselves barricaded in the jail it’s Rio Bravo all over again. Where the original had a gentle humour, a gradually built sense of camaraderie and a frisson of sexual tension (thanks to Angie Dickinson), El Dorado rushes things a bit and lays the humour on too thick. Actually, it’s the comedic elements that do the most damage in my opinion. Much of this is based around the character of Mississippi (James Caan) – in particular, his incompetence around firearms and his questionable taste in hats. What’s worse, though, is a cartoonish fight between Thornton and a drunken Harrah that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Three Stooges short. The climax is also disappointing, the pyrotechnics of Rio Bravo being replaced with a contrived showdown that’s not much more than a damp squib.

In a sense, if you’ve seen one Howard Hawks picture you’ve seen them all. The same themes crop up again and again, namely professionalism and loyalty to one’s comrades. El Dorado is no exception in this respect, we have the tight knit group defying the odds and getting moral support from no-nonsense women. However, there’s a certain flatness to El Dorado, both in the visuals and the reworking of a tried and tested story. The areas where it does score over Rio Bravo are a few of the performances. I can’t honestly fault Dean Martin’s Dude, but Mitchum does bring more weight to his take on the broken down drunk if only because he’s Robert Mitchum. The biggest improvement is the casting of James Caan as the young man taking his first steps in the presence of the big boys. Although the forced jokiness of his character does tend to grate a little after a while he is certainly an actor, something that couldn’t be said for Ricky Nelson. Wayne, of course, is Wayne and it matters not a jot whether he’s playing the sheriff or the hired hand, his star quality ensures that he dominates proceedings. It is interesting to note though that the plot device concerning the bullet in his back was a convenient way to make allowances for the effects of the passage of time and the major health problems he had endured. As for the others, let’s just say that Arthur Hunnicutt, Charlene Holt and Ed Asner were no match for Walter Brennan, Angie Dickinson and Claude Akins. While I’m drawing comparisons, I might just add that Nelson Riddle’s score isn’t a patch on Tiomkin’s – although the title song played over Olaf Wieghorst’s paintings is very memorable.

El Dorado got a 2-disc release not long ago in the US as part of Paramount’s Centennial Collection. I never bothered to pick that one up so I can’t comment on the picture quality, but I do know it offered a variety of extras. The old UK R2 that I have presents the film 1.78:1 anamorphic and it’s not a bad transfer. The image could, I suppose, be a little sharper but there’s really not much to complain about. Image quality aside, the big difference between the old and new releases relates to bonus features, with the earlier disc boasting nothing but a theatrical trailer. Reading back through this, I might seem a little hard on El Dorado. The truth is it’s not at all a bad western and makes for entertaining viewing – the problem is that it’s damned near impossible not to compare it to Rio Bravo, and that’s where it comes up short.