The fact that it is not a proper genre, per se, means film noir is in the fortunate position of being able to cross over all kinds of boundaries. This allows it to shift from its most characteristic low-rent, modern urban milieu to various points in history as well as a wide range of locales. In short, it is versatile enough to hook up with just about any genre one cares to mention. The woman in peril picture is a sub-genre that has a strong connection to the Gothic romance of literature. It typically sees a young woman, often of humble background, who is suddenly thrust into an alien situation or environment, one where the initial attractions are soon stripped of their charm only to reveal some ugly threat beneath. Both in visual and thematic terms, there is ample opportunity to apply the classic noir setup and The House on Telegraph Hill (1951) does so very attractively.

The story has its roots in a very understandable desire to escape the past, to eke out a more promising future, and to do so by assuming a totally different identity. Everything begins in Europe, in the death camp of Belsen to be precise. A young Polish woman Viktoria (Valentina Cortese) endures the horrors and deprivation of the camp and when liberation arrives she impulsively grabs at the chance to make a new start. She takes on the identity of her dead friend Karin in the hope that this will facilitate her move to the USA, where that friend’s young son is being raised by relatives. Since the boy was too young to have any memory of his real mother and no other direct family members are still alive, the deception looks like it may succeed. It seems even more likely when she ends up marrying the child’s guardian Alan Spender (Richard Basehart) and moving to San Francisco to live in the titular mansion overlooking the city by the bay. After the living hell of Belsen this opulent life in California seems almost too good to be true, and so it proves to be as the realization gradually dawns on her that someone is determined to kill her.

A Gothic mystery, or romance, conjures images of the past, of imposing and isolated houses under lowering skies that serve to confine as much as protect. So it is with The House on Telegraph Hill, where despite the contemporary setting the residence itself feels like it is an extension of a bygone age. This is the source of both its allure and its peril – the house is wonderfully realized, ornate and oozing old world luxury within while the exterior has a brooding aura. It draws Karin, and the audience too, with the promise of comfort and security and simultaneously acts as a trap of sorts, a jail with expertly carved balustrades and pillars standing in for the more customary stark iron bars. The location work on the streets of San Francisco add a touch of modern realism to the movie – especially in the excellent sequence where Karin’s car races uncontrollably down those steep hills after the brakes have been tampered with – but those interior scenes are the most atmospheric.

Robert Wise had cut his teeth and learnt his craft at RKO editing for Welles and then getting his chance to direct a couple of dark fairy tales under the supervision of Val Lewton. By the time he made The House on Telegraph Hill he had almost a dozen movies as director under his belt. The opening scenes at Belsen have a suitably grim and gritty tone, similar to what he had captured in the prison sequence in Two Flags West a few years earlier. The pace does flag a little after that and while the build up to Karin and Alan’s marriage needs to be shown, and is done reasonably briskly, it still slows things down somewhat. Nevertheless, once we move to San Francisco both the tone and pace remain remarkably consistent and focused. Lucien Ballard’s cinematography is used to great effect here and he evokes suspicion and unease from such normally mundane images as a branch tapping against a window pane at night or a figure silhouetted in a doorway. Sol Kaplan delivers what I would term a muscular score, admittedly one which some may find overbearing a times.

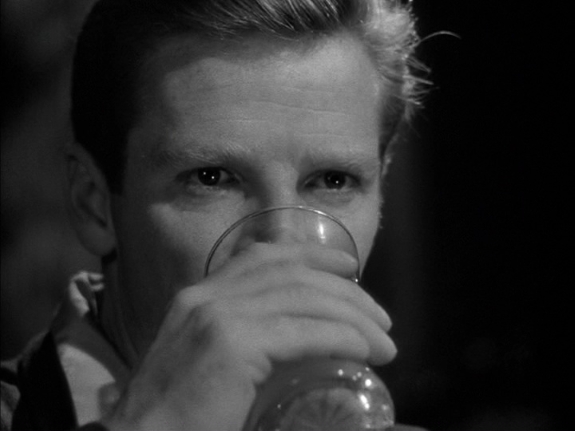

Hitchcock liked to use the generally innocuous glass of milk – see Notorious or Suspicion – as a conduit for something altogether less wholesome, as did Peter Godfrey in The Two Mrs Carrolls for that matter. Wise opts for a glass of orange juice and gets some mileage out of a game of chicken as a result. Richard Basehart started out playing vaguely unhinged types and the fact is he had a certain look about him that encouraged that. There was something about his fair features and impenetrable eyes in those early years that was slightly unsettling and that business with the orange juice, which allowed for and demanded close-ups, leaned into that quality. I believe The House on Telegraph Hill was the film where Basehart and Valentina Cortese met, and they subsequently married. She excels in the concentration camp scenes and their aftermath, touching on the right blend of determination and despair. All told, she does good work and convincingly grows into the part of woman whose increasing confidence is continually being undermined by her fear and a gnawing sense of guilt over the deception she is engaged in. William Lundigan was an actor I have always felt was a bit colorless – that said, he did appear very creditably in Richard Fleischer’s hugely enjoyable noir Follow Me Quietly. Robert Wise had already directed him in the slight but fun Mystery in Mexico and uses his grounded, modest air well in this film. He provides a kind of equilibrium amid all the melodrama. Fay Baker is someone I feel might have had a better or more prominent career based on her work as the nanny/housekeeper, but for one reason or another it wasn’t to be.

The House on Telegraph Hill was a 20th Century Fox movie and has the characteristic gloss of the the studio’s output at that time. It was released years ago on DVD as part of the Fox Noir line and while I’m not sure if it ever made it to Blu-ray there really is nothing to complain about in terms of quality with that old disc. It’s a professional and atmospheric piece of filmmaking and if it’s one of Wise’s less celebrated movies it deserves to be better known.