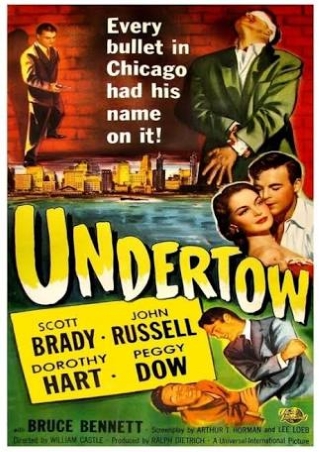

In an era where entertainment gives the impression of becoming ever more bloated and unwieldy, where books seem to be sold by the page count and thus by weight like some indigestible stodge, where even movies which tell essentially pulp stories have running times that defy both logic and the endurance of the human body, it is a true joy to watch a film which is tight and trim enough to take care of business in just an hour and ten minutes. That ought to be a recommendation in itself yet Undertow (1949) has the added bonus of being a remarkably entertaining film noir, William Castle’s best effort in the genre/style in fact.

The war as a watershed – how many times has one come across that particular bromide? Yet its essential truth is undeniable. The image of the returning veteran, those men who dreamed of better days amid the waking nightmare of their years of service, is one familiar to the noir audience. Such men immediately draw sympathy by virtue of the sacrifices they made and this adds an edge to the dangers and depravities they confront on their return home. By 1949 the war was already slipping back into the misty corners of the past, the world was rushing ahead and wasn’t necessarily in any mood to slow down and wait for men trying to catch up with events that had bounded four years and more ahead of them. Tony Reagan (Scott Brady) is introduced as a classic postwar character. He’s a veteran with a vaguely shady past who has grown as a result of his experiences and is now focused on cementing a future for himself and the woman he hopes to make his wife. He has just bought a share in the hunting lodge business of a fallen comrade in arms, and is on his way to Chicago to propose to his fiancée Sally (Dorothy Hart). His last evening in Reno sees him briefly hooking up with a pal from his gambling past Danny Morgan (John Russell), as well as making the brief acquaintance of vacationing schoolteacher Ann McKnight (Peggy Dow). All of these people will cross his path when he lands in Chicago and also lands in deep trouble. The classic noir protagonist frequently finds himself skewered on the horns of a dilemma, trapped somewhere between the pull of his past and typically bad choices going forward. This certainly fits Tony Reagan, a man who was told by crime boss, and Sally’s uncle, Big Jim Lee to stay out of Chicago and away from his niece.

There’s to be no hero’s welcome for Reagan; on his arrival at the airport he’s met by cops who run him downtown for a bit of friendly advice from the precinct captain, namely that he shouldn’t waste any time unpacking. That he ignores this tip shouldn’t come as any surprise, nor should the fact that he is soon slugged, blindfolded and shot, all as a prelude to a frame that looks like fitting him very snugly. If the movie has a weakness it stems from the way it sets itself up as a kind of whodunit where there’s no great mystery with regard to the actual culprit. In this case certain character traits as well as the way a vital piece of information was only available to one person don’t so much point the finger at as turn the spotlight full force on one individual, and when you see who that is then the rest of it kind of falls into place. Still, none of that really matters as much of the pleasure derived from following Reagan on his nighttime odyssey through Chicago trying to keep a half a step ahead of the cops, calling in favors and only realizing the full extent of his peril at the last moment.

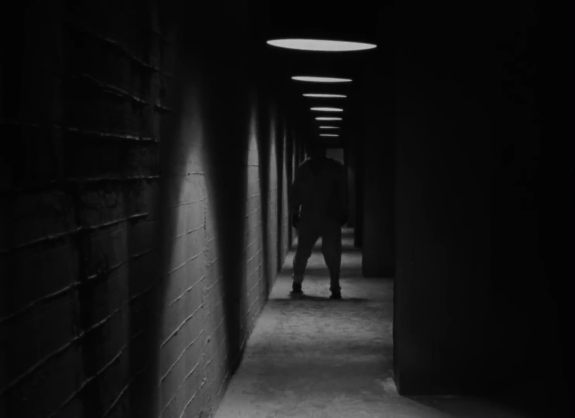

William Castle, like all studio era directors, worked in just about every genre but the bulk of his work fell into three categories: horror, crime and westerns. The horror movies have traditionally gained more attention from critics and fans alike, which arguably says as much for the enduring popularity of that genre as it does for the movies themselves. If I’m being honest, I don’t believe the quality of Castle’s films overall is commensurate with the level of attention they have received down the years. That may come across as somewhat curmudgeonly yet it’s not my intention to do so – I like Castle’s films for the most part and find the majority of them entertaining, just not necessarily always that good. Still, his better work does stand out and I’d have no hesitation in placing Undertow among those better pictures. At this stage in his career there was none of the gimmickry and clowning that would come to be seen as characteristic of the man. Instead, what we get is a compact and atmospheric piece of budget filmmaking that punches well above its weight.

Shakespeare had Caesar remark that Cassius had a lean and hungry look and was therefore dangerous. Perhaps John Russell ought to have been cast as Cassius then at some point in his career for he surely fitted that description. Even though he had heroic leading roles on TV in both Soldier of Fortune and then Lawman, his villainous parts on the big screen tend to be memorable and carry an edge of authenticity to them. He turned in a strong performance in De Toth’s Man in the Saddle and I watched him a while back in Hell Bound and was again impressed. The latter has that typical mean streak that can be found in Bel-Air movies and Russell managed to embody that successfully. Scott Brady was a suitable pick for the lead too, only a few years out of WWII service himself, he had the right combination of toughness and sympathy to be believable as someone with underworld connections but also with the nous to realize his future lay in a different direction. Bruce Bennett’s reassuring presence as the conflicted friend adds solidity to the supporting cast; his well played scenes with his boss and particularly the short interlude in the basement workroom of his home help to ground the story. The two female roles were filled by actresses who had very short screen careers. Peggy Dow appeared for a mere three years between 1949 and 1952 , while Dorothy Hart stretched it out a little longer, running from 1947 to 1952 in features and a couple more on TV. Both had a number of good movies to their credit with Dow possibly squeezing more memorable work in during her brief time as an actress.

Undertow acts as a noteworthy example of the kind of well crafted crime and noir movies Universal-International was capable of producing. It’s gratifying that so many of these are now accessible and can be viewed in good quality, something fans of the studio’s output could only dream of a few years ago. Already released in the US in one of Kino’s box sets, the movie is getting an individual release in the UK ( Amazon link – As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) with plenty of supplementary features via Powerhouse/Indicator in January.