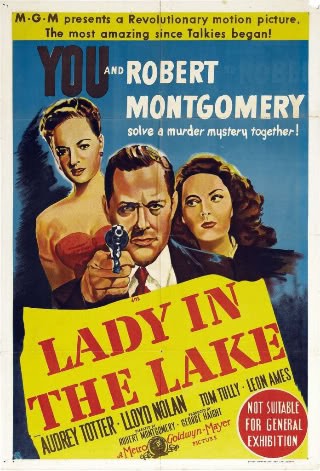

Following on from my previous post I’ve decided to have a look at another seasonal noir. Christmas Holiday (1944) is a movie that seems to slip under many people’s radar, and that may be partly down to both the title and the casting which are apt to give a false impression. At first glance, this is a film that might appear to be horribly miscast but the fact is it works very well. Having said that, the production remains a little odd, but I can’t quite put my finger on the reason. Like Lady in the Lake, the story unfolds over Christmas but, once again, that’s really nothing more than an incidental detail – the timing could easily be changed without affecting the plot in the least.

On Christmas Eve, a newly commissioned army officer, Lt. Mason (Dean Harens), is preparing to fly to San Francisco to marry his sweetheart. However, just before he leaves, he receives a cable informing him that the deal’s off and she’s married someone else. Regardless, he decides to board his flight anyway but neither he nor the audience can be quite sure what he hopes to achieve. As it happens he never makes it to his destination, bad weather forcing his plane to make an unscheduled stop in New Orleans. He allows himself to be talked into visiting an out of town club (basically a bordello, but you couldn’t come right out and call it that under the production code) by the establishment’s PR man/pimp. It’s here that Mason meets Jackie Lamont (Deanna Durbin) and later hears her story. The character of Mason doesn’t really serve any purpose other than that of a narrative device – he’s simply there to provide an everyman perspective, the eyes and ears of the audience as a tale of deception, murder and obsession unfolds. Jackie explains that she’s been using an assumed name, her real one being Abigail Manette, since her husband’s conviction for murder. Via two separate flashbacks she relates how she met, fell in love with and married Robert Manette (Gene Kelly). Manette turned out to be a wastrel blueblood, fallen on hard times, with unsavoury characteristics that are mentioned only in the vaguest terms. This is all pretty standard fare for a noir thriller, but it’s the creepy relationship between Manette and his mother (the Spiderwoman herself, Gale Sondergaard) and the stifling home atmosphere that sets this movie apart. I’ve come across a few theories which try to explain exactly what’s “wrong” with Manette and the nature of his relationship with his mother, but I’m not entirely convinced by any of them. The script makes it clear enough that this is a man with a deeply flawed character but that’s about it. However, I haven’t read the Somerset Maugham story on which the film is based so I don’t know if that casts any further light on the subject.

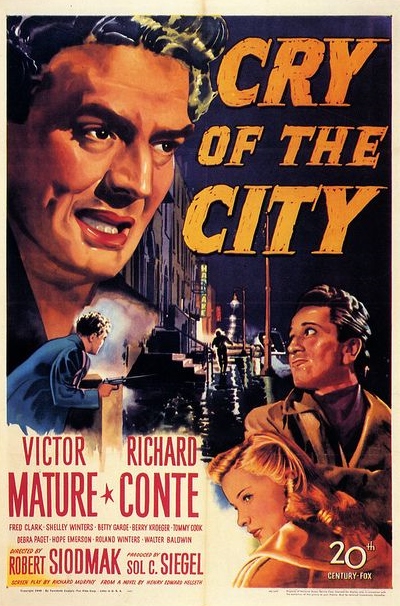

Deanna Durbin is credited with being the saviour of Universal as a result of the popularity of her lightweight musicals in the 40s but Christmas Holiday was a major departure from the usual formula for her. She does get to sing two songs, in her role as night club “hostess”, but this is a straight dramatic role. I thought she performed very well, and managed to handle the necessary transition from wide eyed innocent to world weary fallen woman quite convincingly. Gene Kelly is another performer not normally associated with dark, dubious characters but his Robert Manette is not at all bad. Seeing this jaunty, amiable figure jarringly transformed into a mother-fixated murderer has an unnerving quality that’s highly effective. Gale Sondergaard always brought an eerie, otherworldly feel to the parts she played and it fits right in here. The middle section of the film, told in flashback, takes place mainly in the confines of the Manette house, where Sondergaard seems completely at home amid the relics of a faded past. It’s this part of the movie that lends the slightly odd sense that I alluded to at the beginning. Maybe it’s the curious family dynamic, or the feeling of stepping into a world removed from the present – I honestly can’t say, but everything just feels a little off-centre in these sequences. This was Robert Siodmak’s second Hollywood noir, following on from Phantom Lady. It’s not quite up to the standard of his previous picture and lacks a little of the visual flair that he usually brought to the table. However, he does some good work in the club scenes, and the unusual architecture of the Manette house offers opportunities for some interesting shots.

As far as I know the only DVD of Christmas Holiday is the UK R2 from DDHE (EDIT – it appears there’s a Spanish release also available – see comment #1 below). It offers a pretty good transfer of the movie with no major damage or distraction on view. The only extra feature provided is a gallery of production stills. All in all, this a satisfying little noir that moves along nicely and has good performances from all the main players. For me, the casting of Kelly and Durbin worked, although I can see how it might lead to the film being ignored by some – fans of the two leads may be alienated by the atypical roles and storyline, and noir lovers may be put off by their presence. Nevertheless, I think the movie has a unique quality and is definitely worth a look.

With the Christmas juggernaut bearing down ominously, I doubt if I’ll find the time to post another piece before the holidays. So, I’d just like to take the opportunity to wish all those who have followed, commented on, or simply dropped by this blog from time to time the best of everything over the holiday period. Here’s hoping you all enjoy a happy and peaceful Christmas.