The Gothic mystery / romance characteristically placed wide-eyed young females from generally sheltered backgrounds in perilous situations. As often as not, they found themselves alone, or practically so, in some rambling old pile they had inherited and threatened by some as yet unknown figure. It’s a hoary old trope, but a it’s also proved to be an attractive one and pretty successful as a consequence. The classic variant still turns up of course and it has also been tweaked and updated to make the standard formula a better fit for changing circumstances and the demands or tastes of audiences. Female on the Beach (1955) is essentially a modernized take on the Gothic mystery. Sure the trappings have been altered and the setting has waves gently lapping on sultry shores rather than launching raging assaults on mean and jagged rocks, but the core elements remain in place – there’s a lone woman taking up residence in an expensive house, a romance with a shadowy and potentially dangerous man, an escalating series of threats and a correspondingly mounting sense of panic and anxiety. As is frequently the case with a lot of this type of material, some of it works very well while other parts suffer from exposure to the overheated atmosphere.

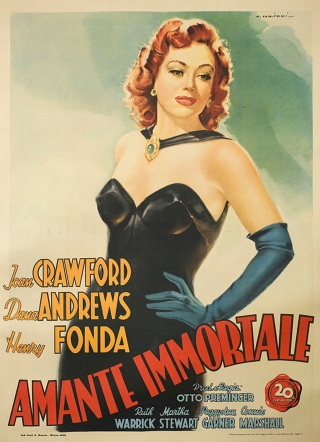

The first female seen on a beach in this movie is one who has just taken a swan dive off the veranda of her seafront home. She had been drinking, heavily, quarreling querulously with a lover and then in a fit of alcohol soaked remorse and self-pity rushed out onto the balcony to stumble and crash through the guard rail. The last we see is the final twitch of her hand, flicking farewell to the busted remains of a brandy balloon. The entire business had an air about it that was as much pathetic as it was tragic. One out, one in – the next arrival is the actual owner of the house. This is Lynn Markham (Joan Crawford), the widow of a big time gambler and a woman looking for nothing so much as solitude. What she ends up getting is the initially unwelcome attention of resident beach bum Drummond Hall (Jeff Chandler). He seems to be suspiciously familiar with the house, and there are little relics of his previous visits littering almost every corner of the place. None of this should be much of a surprise; Drummy (as everyone calls him) is an unapologetic gigolo, albeit something of a reluctant one. He was the man who exited the house pursued by the drunken entreaties of the last tenant just before she moved out permanently and suddenly. He appears to be set on continuing where he left off, business is business after all and a guy has to make a buck whatever way he knows best. Lynn Markham doesn’t intend to become the next mark to pick up Drummy’s checks though and tells him so in no uncertain terms. All of this recalls the tale of Zeus once realizing that the fox that can’t be caught and the hound that can’t lose its prey sets up a paradox of Olympian proportions. In short, something’s got to give. Well it does, love blossoms or lust triumphs – take your pick. And yet there’s a lingering doubt regarding the death of Lynn’s predecessor – accidents ,suicides and murders all produce the same result and it’s easy to mistake one for the other. With a persistent and dissatisfied police lieutenant lurking in the background, Lynn runs the gamut of passion, suspicion and outright fear as she falls for Drummy yet can’t shake the feeling that he may be looking to dispose of his catch as soon as he has secured all the wealth and benefits that come with it.

Director Joseph Pevney was on a solid and at times hugely impressive run of movies throughout the 1950s. There were some misfires and a few frankly humdrum efforts along the way, and some like Female on the Beach which look stylish despite an inherent modesty in terms of production, tease and flatter to deceive in scripting and development, and still manage to be entertaining despite some major flaws. The movie raises questions about the nature of love and betrayal, the importance of trust and the brittleness of human relationships. And the ending, the conclusions reached, is less than satisfactory. It ties everything up in a neat enough way but that doesn’t make it particularly convincing, nor I would argue does it offer a resolution with any promise. None of this is the fault of Pevney of course, the script being an adaptation by Robert Hill of his own play. Pevney, and cinematographer Charles Lang, create some attractive images despite or inspired by the natural staginess of the material. Somehow though, the melodrama and the thrills don’t blend as seamlessly as they might, curdling instead and leaving the finished product lumpy where it ought to have been smooth.

Jeff Chandler made a number of movies with Pevney and all that I’ve seen have been worthwhile on some level. Female on the Beach does have a certain superficiality to its sandblasted Gothic chic, but Chandler always brought an enticing mix of authority and vulnerability to his roles regardless. While dissatisfied self-awareness crossed with brooding calculation isn’t the easiest look to put across, he succeeds in doing so. Joan Crawford was nearing the end of her strong mid-career revival, the slightly trashy but very enjoyable Queen Bee and the very fine Autumn Leaves would soon be followed by a run of exploitative titles of gradually diminishing quality. Female on the Beach had her running on autopilot, suffering, emoting and tossing out some stinging barbs but never stretching herself. Jan Sterling was generally good value in any movie she appeared in and spars successfully with Crawford here. That said, the tone of her performance overall is ramped up a little too high, and again I feel the script is to blame for that. Cecil Kellaway and Natalie Schafer are wonderfully seedy as Chandler’s sponsors and handlers while Charles Drake is solidly unremarkable as the dogged detective – I think I prefer him in his more ambiguous roles.

Female on the Beach is easy to access for viewing, as are so many Universal-International movies these days. It was released on DVD in the US long ago in a box of vaguely noirish thrillers and then on Blu-ray by Kino. I have the UK DVD that Odeon put out some years ago and I think it’s a more than satisfactory presentation. To sum up, Pevney does his customarily slick job, Chandler and Crawford add some star power, but the script rarely rises above the mediocre.

This launches a short series of posts on the movies of Joseph Pevney that will be featured this summer.