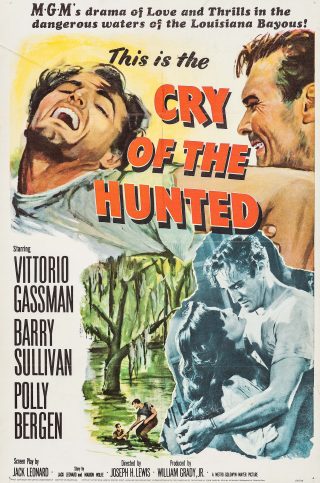

It could be argued that every story is at heart a tale of pursuit, a fictional quest where the prize sought might be material (money, treasure, etc) or spiritual (love, contentment, redemption, revenge, and so on), or the quarry might be of the classic, and slipperiest variety: a human being. For the viewer, the race to capture or recapture a fugitive always tends to raise the dramatic stakes, providing scope for shifting sympathies and asking questions about the role of, and indeed the relationship between the hunter and the hunted. Such should be the case with Cry of the Hunted (1953), where both parties involved in this particular game of hide and seek come to realize that their objectives might be different to what they had initially believed. Yet this is only partially fulfilled and the result of it all is that the movie ends up pulling some of its punches.

Speaking of pulling punches, there’s not much of that in the early stages, when Lieutenant Tunner (Barry Sullivan) tries to get convicted getaway driver Jory (Vittorio Gassman) to dish the dirt on his accomplices. The outcome is a bruising and punishing encounter, but one which makes it clear that both men, despite their entrenched positions on opposing sides of the law, have a grudging mutual respect. A traffic accident in downtown Los Angeles affords Jory the chance to escape, making use of the iconic Angels Flight in Bunker Hill, and he grabs his opportunity with both hands. The galled lawmen now have red faces to go with their grey suits and the only way to cool this situation is to arrange for the recapture of the prisoner as soon as possible. Jory is a man of the Bayou, the Louisiana marshland where the alligators aren’t the only threat, and it’s not hard to figure out he will be heading back there, back to his home and his wife. And so it is that Tunner is sent across the country to bring the fugitive back. He’s on top of things soon enough, almost laying Jory by the heels when he intercepts the freight train he is riding, and then tracks him to his shack in the swamps. A shade too much overconfidence is his undoing though, turning his back at the wrong moment leads to a concussion, a bellyful of filthy water, and a stay in hospital. All of this means the trail will need to be picked up once again, this time in the company of a colleague (William Conrad) who is keen to grab his job.

The entire setup here is most promising. The plot has a good deal of potential, the setting offers danger and atmosphere, and Joseph H Lewis as director always holds out the hope of some interesting visual flourishes. Lewis does get some value from the swampy surroundings, and the short sequence involving Sullivan’s fever dream (a shot from which can be seen above) is attractive even if it doesn’t actually add much to the story. However, for all that promise and potential, the finished movie falls a bit short. Now, it is never boring and Lewis keeps the pace up and the running time down, but the development of the plot is rather flat and predictable. Even a low budget effort such as The Ride Back (coincidentally, also featuring William Conrad in a prominent role) flips expectations to an extent by having hunter and hunted virtually changing places and gaining some personal insight as a result. In Cry of the Hunted, however, there is none of that.

Sullivan starts out as a well-meaning and conscientious guy with a hard edge and he never wavers or strays from that path, winding up in essentially the same place as he began. The part is a solid one, playing up the brash needling side of himself that Sullivan often showed and shoring it up with a strong core of decency and humanity. I haven’t seen a lot of Gassman’s work, which probably says much about my limited exposure to Italian cinema, but his character does get to undergo a touch more growth. I emphasize the fact that it is only a touch more though; there’s never really much doubt that his heart is in the right place or that he has it within him to come good. I reckon the writers missed a trick in the last act and should have had Sullivan laid up with an injury and needing to be saved by Gassman rather than the other way around. I seem to be on a bit of a William Conrad kick just now and he is good value as Sullivan’s subordinate and competitor. He seems to have been set to take on a meaner role (goading Gassman in the early stages, beating up a witness) but the script only leads him a short way down that particular path before allowing his better nature to take charge. Polly Bergen (Cape Fear, Escape from Fort Bravo) drifts in and out of the picture in a small role as Sullivan’s wife.

Cry of the Hunted is an MGM production, but it was not one of the studio’s top line pictures. It’s a small affair with some attractive location shooting and a tight, self-contained cast. Even second string movies from such a big studio have a fair bit of polish and it’s interesting to see MGM branching out into this more socially aware material, although it is nowhere near as challenging as it could have been when one takes into account the strong initial premise. I think it is fair to say it never really fires on all cylinders and it feels like a minor work from Lewis. Nevertheless, any opportunity to spend an hour and a quarter or thereabouts in the company of actors like Barry Sullivan and William Conrad is not something I would ever consider a chore. As for availability, it should be easy enough to locate seeing as the Warner Brothers Archive released a good-looking copy a few years ago. So, it’s definitely worth checking out and enjoyable enough as far as it goes, as long as it is approached with realistic expectations.