On the outside looking in doesn’t do anybody any good.

That one casual line in Foxfire (1955), spoken by one of the most hard done by and neglected characters in the movie as it happens, goes a long way towards catching the spirit and flavor of the entire picture. In a sense, all of the characters are outsiders in their individual worlds, some by chance and others by choice or design. This is a strong theme, one many of us will be able to identify with at some point in our lives and thus a solid bedrock on which to construct this story which I’d say is three parts melodrama and one part modern western. That part picks up on and weaves into the blend perhaps one of the more interesting, challenging and progressive thematic threads to be found in the fabric of the 1950s western, the clash of cultures which was inevitable in a new land and the dramatic tension growing out of that.

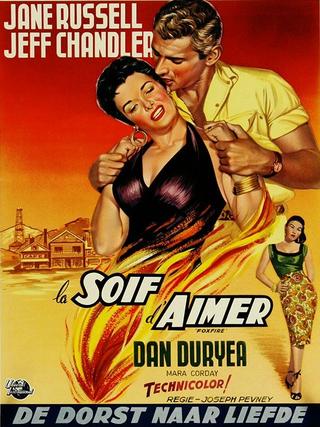

A desert highway, one of those arrow straight and seemingly endless thoroughfares that we viewers have traveled many times. Our companion on this occasion is a lone woman, Amanda Lawrence (Jane Russell), speeding along until she gets a flat tire. With no help available, she sets off on foot, burdened with what look like the assorted fripperies of a shopping expedition. There can’t be any doubt that this chic and carefully coiffed lady is very much an outsider in the primal landscape, a refugee from 5th Avenue cast adrift in the dust and heat of the southwest. Then out of that shimmering haze comes a jeep carrying two men – miner Jonathan Dartland (Jeff Chandler) and doctor Hugh Slater (Dan Duryea) – and we’re off. Amanda is clearly taken with Dartland and he’s at least interested in her. What follows is a love story but it’s not a smooth one, and I think it’s questionable in the end what all of the protagonists are in love with. In fact, despite the relatively neat conclusion, those questions are only partly answered and I feel there’s a suggestion that they will rear their heads again.

As far as I can see, the characters are being pulled in different directions partly by their disparate backgrounds and partly by their status as outsiders. Beginning with Dartland, or Dart as everyone refers to him. We learn very early on that he is half Apache, with a mother who has returned to the reservation and wholly integrated herself back into tribal life after the death of her husband. He is forced to endure some bigoted and prejudiced attitudes – including one thoughtless gaffe on the part of Amanda before she learns about his heritage – but tends to brush them aside. He insists it means nothing to him but a couple of understated moments call this into question – the brief flash of hurt in his eyes when Amanda makes that crack about Indians, and then later the diffidence and self-consciousness he displays when entering the club for their first date, not to mention the haste with which he beats his retreat.

For all Dart’s claims of not being affected by his background, he’s very much aware that he is outside looking in. And he cannot fully break with his past; he avoids talking about his mother’s people, keeps his memories quite literally locked away and reacts with petulant sensitivity to their discovery. Nevertheless, the tone of his relationships, especially with Amanda is dictated by his upbringing, his instinctive prioritizing of self-reliance as well as his resorting to the physical as opposed to the emotional act of love when confronted with conflict. As I mentioned above, I’m unsure whether he’s confident what he’s in love with – his wife or his ambition, and that siren song of kith and kin holds a powerful attraction.

What of Amanda? Is she any less an outsider? A socialite on vacation drawn to something attractive, and she does refer to Dart time and again as pretty in a neat subversion of traditional objectification. She labors hard to adapt to the harsh conditions of the mining town and also has to deal with the whispers of her own past tempting her to throw it all up in favor of the ease and plenty she was accustomed to. Again, does she really know what she wants – the rugged ideal of her imagination or the the reserved figure of reality?

You can always tell a script has depth when it adds meat to the bones of the supporting characters ; this one is from the pen of Ketti Frings, who had already written a few very good films noir as well as another Joseph Pevney / Jeff Chandler picture Because of You, and I’m keen to track that one down now. Dan Duryea’s boozy doctor could have been a mere caricature, a sidekick with a bottle who bumbles in the background. However, the character isn’t written with such broad strokes, there are layers present which are only gradually uncovered. He doesn’t truly belong either, another blow in from another world, a drunk as a result of personal trauma and casting around for a means to escape his circumstances. Duryea excelled at playing heels and it’s therefore not much of a surprise when his cunning and manipulative side rises to the surface. The one who arguably suffers this most, albeit with almost superhuman stoicism, is his nurse/lover played by Mara Corday. Like Dart, she is half Apache yet the barriers separating her from white society are even more entrenched. There’s something both outrageous and touching about her quiet patience and devotion to a man who habitually neglects her to the point of naked disrespect. Then there’s that wedding scene, where she is looking in in every sense, relegated to a place outside in the company of hookers and other undesirables. She is in a very real way a peripheral figure and is assigned only a limited amount of screen time, but her presence and its effect on the viewer is significant. Somehow, the casual acceptance (by herself as well as by the other characters, and perhaps even more so on her own part) of her regular social exclusion and the flippant exploitation of her affections do as much to highlight prejudice as some of the more direct and overt references involving Dart.

I’ve watched and featured a number of Joseph Pevney movies this year and Foxfire is probably the most enjoyable one so far. I appreciated the understated way the drama unfolds and this is particularly true of the key scenes. The film has that appealing look that is so characteristic of Universal-International productions and William Daniels’ Technicolor cinematography honestly is quite breathtaking at times. The setting matters too, it feels entirely appropriate in this case that everything revolves around a mining settlement in the Arizona desert. The location offers a tangible link to the classic western and then there is that sense of the ephemeral, of a place hastily built amid a permanent wasteland – Chandler’s character dreams of making it a lasting settlement but there’s that nagging doubt again, as in his personal affairs, over how sure the foundations will be. Somehow the raw purity of the scorched backdrop offers a contrast to the transitory desires, ambitions, jealousies and angst of this group of people, none of whom appear to genuinely belong.

As for availability, there is a Blu-ray which has been released in the US and I understand it offers a fine presentation of the movie. Sadly, I’m Region B only when it comes to Blu-ray so I had to find other options. There has been a DVD release in Italy that is hard to fault as far as the picture quality is concerned. It might be standard definition but the 2.00:1 widescreen image is sharp as a pin, clean and colorful. Sure there are better melodramas to be found and the theme here may not have the kind of universal resonance that typically adds greatness. Nevertheless, this is a good movie, and it mostly worked for me, raising a number of issues I could relate to as well as providing an hour and a half of polished, solid entertainment. My recommendation is that anyone able to access this title should check it out.