The frame up and revenge are classic noir ingredients, saps suckered into taking a fall and then looking to square it with those responsible have kept the motors humming on many a dark crime drama. Cry Danger (1951) is based on these themes, with thoughts about loyalty and love tossed into the mix as well. The movie is a bit like an old friend in the sense that it is packed to the rafters with familiar elements, and like an old friend I’ve visited it a few times over the years. I guess that’s another characteristic that applies to most films noir; they never seem to wear out their welcome no matter how many times they’ve been viewed, the setups and situations becoming something akin to reminiscences among acquaintances.

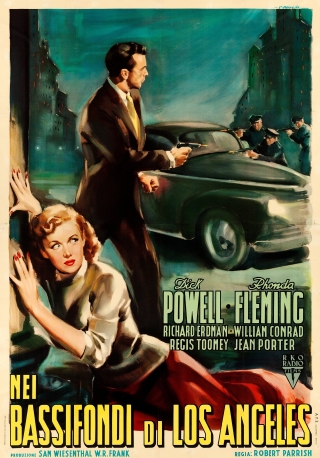

I mentioned revenge in the opening sentence, but the fact is that Cry Danger is more concerned with a quest for justice than anything else. Rocky Mulloy (Dick Powell) has just caught a break, even if he’s not thinking of it in those terms as he steps off the train in Los Angeles. He’s fresh out of prison, having served five years of a life sentence for his part in a killing and robbery. Why is he back on the streets so soon? Well aside from the fact he knows he was not guilty of the crime, a witness has just turned up who could corroborate his alibi from all those years ago. Delong (Richard Erdman) is a one-legged ex-serviceman who is only now able to back up Mulloy’s claims that he was drinking in a bar with a group of Marines when the heist was going down. Mulloy is naturally sore that he’s essentially lost those years but he’s also keen to find the real perpetrators, both for his own vindication and to secure the release of a friend who has also been jailed for the crime. In a neat twist, it’s revealed very early on that Delong never spent the evening drinking with Mulloy, never even met him before. He’s just a guy on the make who reckons that helping out like this will mean he can come in for a cut of the $100,000 take which was never recovered. Mulloy’s search for justice takes him to the trailer park where his friend’s wife and his own former fiancée (Rhonda Fleming) is living, and then back into the murky world inhabited by crooked bookie Castro (William Conrad). By the end, after more crosses than there are factors to describe them and some gratuitous violence on the side, Mulloy digs his way to an unpalatable truth.

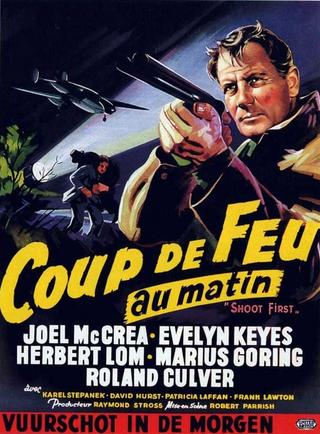

Cry Danger was the first movie directed by Robert Parrish. He’d served a long apprenticeship in the editing and sound departments and worked on a number of films for John Ford. By 1951 he was therefore in a strong position to take what he’d learnt and craft his own pictures. Cry Danger saw him off to an impressive start and he made a series of mostly good, and in a handful of cases truly excellent, films throughout the decade. This was also the first of four productions for Parrish where William Bowers was involved in the writing. And the script here is one of the strengths, tightly paced and twisty without becoming unnecessarily complex, it benefits from some marvelously snappy dialogue that catches the flavor of the hard-boiled idiom. Unlike a lot of films noir, there isn’t a great deal of overt social commentary. There’s not, for instance, much if any background provided for Mulloy, nothing to hint at how this man got himself tied up with bookies and crooks in the first place. The one concession to the consequences of life in the post-war world is the portrayal of Delong. This disabled veteran makes only the briefest reference in passing to the loss of his leg, but there is a suggestion that his prodigious drinking has its roots in that injury. A good deal of that too is treated in a light and offhand manner, though there is one point where the possibility or advisability of his trying to quit is raised. The wistful look, one tinged with a shadow of desperation, that passes over Delong’s face alludes to some inner suffering. Nothing much is made of this but it is there for the viewers to take on board should they wish to do so.

Dick Powell had grown confident and comfortable in roles such as this, a tough and smart guy who has some blind spots when it comes to friends. The clever patter rolls of the tongue easily and he has an excellent foil in Richard Erdman who was just as quick on the quip. Rhonda Fleming is arguably too attractive to be entirely believable as someone living out of a trailer park, though the fact her husband is doing time kind of justifies this. The path of her relationship with Powell’s character is complicated and, bearing in mind how everything is resolved in the end, it’s quite a subtle piece of acting on her part. As such, Cry Danger is certainly one of those movies where repeated viewings help to emphasize just how carefully she played the role. I’ve already referred to Erdman and it will probably suffice to say that his deadpan wit adds considerably to the film and makes it all the more enjoyable. In support, William Conrad never looks like someone trustworthy although he never comes across as all that menacing either – corrupt and devious, but not all that threatening. Regis Toomey was born to play cops and did so on numerous occasions. He had that weary practicality about him that felt authoritative and he uses it effectively as Powell’s ever present shadow.

Olive Films released a restored print of Cry Danger well over a decade ago now and it still looks fine. It’s a slick and pacy noir with the kind of plot that avoids overdoing the complications yet offers Powell the type of cool but tough part he excelled at playing. Highly watchable.