I mentioned recently how films set on trains or in creepy old houses are some of my favorites, I should have also included ships and boats while I was at it. Mysteries and thrillers benefit enormously from these confined settings: the sense of claustrophobia is heightened, and then there’s the knowledge that the hero can only run so far. Journey into Fear (1943) has its hero boxed up on a decaying old freighter in the middle of the Black Sea, surrounded by a gallery of grotesques and living in fear of his life. For a film that runs only a little over an hour it’s packed full of memorable scenes, images and characters that tap into a strong noir vibe.

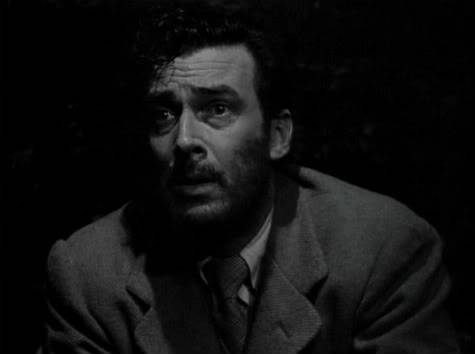

Howard Graham (Joseph Cotten), an engineer employed by an American armaments company, is in wartime Turkey on business. He’s a typical everyman character and, by his own admission, not a very exciting person. When the company’s local rep decides to take him out for a night on the town, Graham finds himself abruptly swept away into a world of intrigue, assassination and terror. It all begins in a night club where Graham narrowly avoids death. The local man, a fawning and obsequious type by the name of Kopeikin (Everett Sloane), has dragged the reluctant Graham into this slightly seedy cabaret, plying him with liquor and women. During an illusionist’s act, for which he has ‘volunteered’, a shot rings out in the darkness and the magician takes the bullet surely meant for Graham. Before the outraged and confused engineer even has time to draw breath he’s hauled off to a meeting with the chief of the Secret Police, Colonel Haki (Orson Welles), who has him bundled aboard a stinking old tub to spirit him safely out of the country. This is the pattern the movie follows, there’s always someone else making decisions for the increasingly bewildered Graham. Of course he tries to wrest the initiative but, in classic noir fashion, he’s always a victim of fate rather than a master of his own destiny. The scenes aboard the ship are full of menace, emphasised by the low angle shots and the deep, dark shadows that seem to follow Graham everywhere. The threat looms even larger when a short stopover allows the assassin Banat (Jack Moss) to come aboard. This character hasn’t one line of dialogue throughout the film but it’s that chilling silence and the bland countenance masked by pebble glasses and a vaguely ludicrous hat that add to his creepiness. When Graham finally disembarks he makes a break for freedom, but fails to get very far. This does, however, set up a thrilling climax atop a hotel ledge in the pouring rain that ties up most of the loose ends.

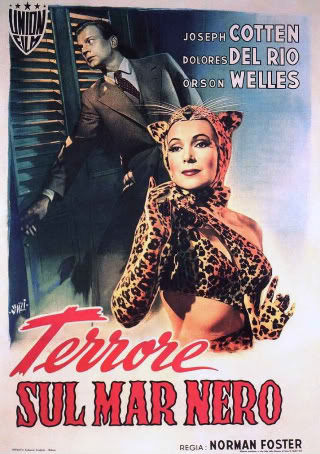

Journey into Fear is an adaptation of one of Eric Ambler’s finest novels with the screenplay credited to Joseph Cotten. Being a huge and unashamed admirer of Ambler I’m always pleased to see his work represented on the screen, and this movie retains much of the flavor of his writing. Aside from the scripting credit, Joseph Cotten turns in a good performance as the baffled engineer who’s always on his guard but never quite sure who to trust. His plight is one that’s frankly hard to swallow, and there’s a nice little scene where he tries to convince the ship’s captain of the danger he’s in only to have the grizzled old codger laugh in his face. Dolores del Rio (who had a relationship with Welles) first appears as a leopardskin clad dancer in the early night club scene and maintains that feline aura throughout as she slinks around sexily in pursuit of our hero. The rest of the cast (largely drawn from the Mercury players) mainly turn in small but memorable cameo roles. In particular, Jack Moss, who was in fact Welles’ accountant, turns the blood cold every time his ungainly bulk lumbers into the frame and his impassive assassin remains one of the highlights of the movie. Orson Welles plays another of those larger than life figures that seemed an extension of his own personality to great effect in the few scenes where he appears. His trademark slow-quick-slow delivery and the darting eyes that twinkle mischief one minute and glower thunderously the next are ideal for the shady yet menacing Colonel Haki – incidentally, the character of Colonel Haki is one that showed up again in Ambler’s The Mask of Dimitrios. In truth, Welles’ massive presence dominates the film and his fingerprints are to be found all over the production. Although Norman Foster is credited as director it’s clear to anyone familiar with his work that Welles, at the very least, exerted a huge influence over the shooting. For example, the climactic chase along the slick hotel ledge in the storm uses the kind of dizzying overhead angles that Welles was fond of.

For a number of years now Warners have been promising that a DVD with a restored print of Journey into Fear is on the way in the US, however it still remains a no show. The French company Montparnasse have released the movie in R2 though, and there’s really not much wrong with that edition. The print used is actually in pretty fair shape with good contrast and sharpness, sure there’s the odd scratch and speckle here and there but nothing to fret over. There aren’t any extras save a brief introduction (in French naturally), but if it’s a good print of the movie itself you’re after then the Montparnasse release is very definitely acceptable. Journey into Fear is a stylish little noir film that benefits from the Welles touch and has the quirkiness that’s often found in films he graced with his presence. The pace may feel a little rushed at times but I prefer to think of that as emphasizing the urgency of the situation and the danger the hero finds himself in. It certainly gets my recommendation.