Everybody loves a winner, right? Well actually they don’t, there are those whose behavior draws crowds in the hope they are going to see them get a licking. It’s not just winning, rather it’s how a person wins and perhaps also why they win or even want to. Once upon a time, success in sports, and indeed life itself, was predicated not only on the results achieved or the prizes attained but also on the manner in which the game was played. Is boxing the ultimate sport? Perhaps it was at one point, or perhaps it only appeared to be so for a brief moment in time before sliding into a seemingly unrepentant morass of glitz and trash-talking. Still and all, there is at the heart of it all the seeds of nobility, and I think Iron Man (1951) attempts to tap into some of that. There is something about the image of two men pitting themselves against one another in a formalized setting, mathematically bounded spatially and in terms of timing, equipped with nothing but their guts, guile and sense of fair play. It appeals on an almost atavistic level, but that appeal is heavily dependent on both parties adhering to the rules, the rules of the game and by extension of humanity. It’s only when those rules are bent or warped either by the antagonists or those observing them that some of the purity is lost.

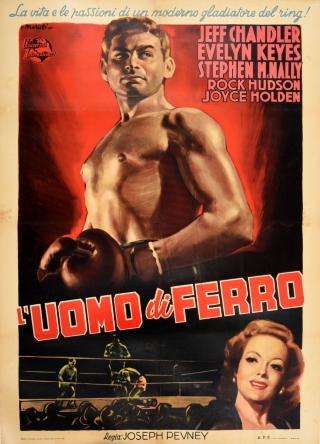

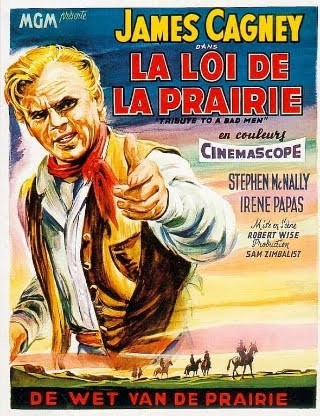

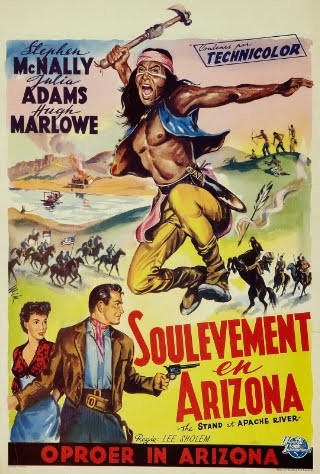

If the duel promises a contest of honor, the same quality cannot always be said to be evident among those watching it. One hears about the roar of the crowd, but what lies behind that? Look at the eyes and listen, especially listen. All the passion that is embodied in the strained faces, the anxiety, the fear, the trepidation and for some the blood lust. And this is amplified in the sound, cheers and jeers, and if the latter dominates then what? This is the scene presented at the beginning of Iron Man – the announcer holding sway in the center of the ring, barking into the suspended microphone as the arc lights cast their harsh gaze, heralding the start of a world championship fight, calling out the names of the contenders. As the reigning champion steps up the voice of the thousands banked around the roped off area rises not in celebration but in reprobation. Coke Mason (Jeff Chandler) is the focus of this disapproval and he appears to drink it all in dispassionately, feeding off the negativity surrounding him. The view shifts to the spectators, one woman in particular. This is Rose (Evelyn Keyes), Mason’s estranged wife and she sits detached from the screams and boos, thinking back to how these circumstances came to be and of her own role in bringing them forth. We dissolve into a long flashback as Rose leads us back to the coal mines of Pennsylvania, to the man Coke Mason once was before he set out on the path that has led him to fortune and infamy. So we follow Mason as he embarks on the journey out of the grime and hazards of the mines, facing off against mindless prejudice from a belligerent co-worker, finding himself practically reborn after the trauma of a cave-in, on towards his early days as a rough and ready prize fighter egged on by Rose and his ambitious brother George (Stephen McNally). Right from the off Mason is a slugger without technique and, more crucially, without a true sense of why he is fighting. Maybe it would be more accurate to say, he does know why he’s fighting – for the money of course, but also as a reaction against his own deep personal insecurity – it’s just that he is incapable of controlling the fires in his soul. This is what drives him, the internal rages which once ignited are virtually unstoppable and threaten both his opponents and himself.

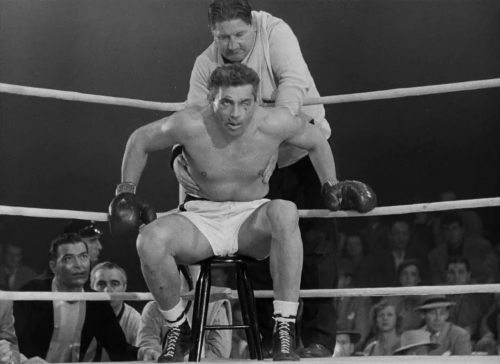

Iron Man boasts a George Zuckerman/Borden Chase screenplay from a novel by W R Burnett. Those are pretty impressive credentials right there and the movie moves smoothly through its hour and twenty minute run time to a conclusion that some might see as predictable but which is deeply satisfying for its redemptive and restorative qualities. Director Joseph Pevney keeps it fluid and scenes are generally well paced. It’s the type of material that suited the talents of Pevney and the team around him and cinematographer Carl Guthrie creates some fine images, especially the early stuff below ground in the mine and then later in the fight sequences. Pevney and Guthrie shoot and cut expertly here, making use of starkly lit close-ups alternating with wider pans to draw the viewer into the fight and heighten the tension. The outcome might not be in serious doubt yet the stylish way it is presented is a pleasure to watch, and the emotional and thematic payoff is undoubtedly worth it.

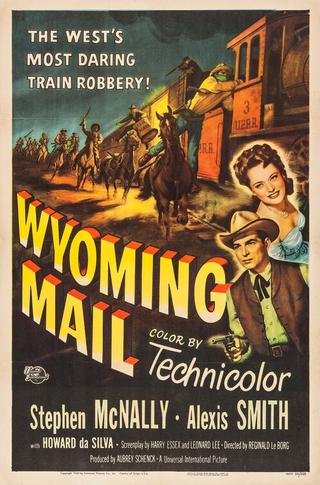

Jeff Chandler handles the conflicted aspects of his character as well as one would expect. The reluctant fighter who is simultaneously motivated and frightened by what he carries around inside offers him plenty to play around with. He reportedly put in a fair bit of work on the practical physical aspects of the role and the fight scenes benefit from that. He never displays much grace in those moments, but that’s the part he’s portraying, a fundamentally awkward man who powers his way to dominance without bothering about the style. Rock Hudson is fine too, albeit in a lighter role as Chandler’s friend who moves from second in the corner to rival in the ring. Stephen McNally was never less than versatile and his flashy turn as the brother who rarely lets a scruple stand in the way of a fast buck is up to his typically high standard. His realization of the harm he has caused, alongside Evelyn Keyes’ similar conversion, is central to the resolution. Keyes cultivates her character nicely as the movie develops and her move from opportunism to remorse feels very natural. Jim Backus drifts in and out of proceedings as a reporter who ends up moonlighting as a promoter. It feels like an odd progression at first but it’s another key role and makes sense as the story unfolds.

Iron Man is another of those Universal-International titles which Kino have scrubbed up and marketed on Blu-ray in their impressive film noir line. The movie does undoubtedly highlight moral ambiguity and explores some dark places in the soul, and it’s a boxing film. Even so, I’m not sure I’d class it as film noir – others may see it differently and I can’t say labeling it or categorizing it in this way bothers me much one way or the other. It pleases me to see this film available in good shape and that’s really all that counts. In the final analysis, this is a good movie with the cast and crew all turning out very creditable work.