Something about the mid-range westerns that Universal-International was producing in the 1950s points to that hard to define quality which makes the genre so attractive. It’s partially down to the look, the color and locations, and partially the no nonsense style of storytelling. It’s not always easy to come up with a movie that offers entertainment while quietly making some point about a given issue. Universal-International movies often managed this, and the westerns directed by George Sherman during his time at the studio from the late 1940s on are a good example of this. In particular, his films that give some prominence to Indian or Native American affairs sidestep the ponderous or pretentious pitfalls that have bedeviled many a well intentioned movie. War Arrow (1953) will not be found on any ‘best of’ lists and there’s no reason why it should; it breaks no new ground, nor does it do anything especially startling. However, the film is enjoyable, it uses its strong cast effectively, and Sherman’s characteristic sympathy for the Native American is subtly and seamlessly blended into the narrative.

War Arrow is one of those westerns that takes its inspiration from some real historical event, in this instance the recruitment of Seminole tribesmen as cavalry scouts. I say inspiration here because it is a movie after all, not some attempt to represent real history. The film starts out with Major Brady (Jeff Chandler) and two sergeants (Noah Beery Jr and Charles Drake) on their way to Fort Clark, Texas. They have been sent to help in the struggle to contain the raiding parties of Kiowa that have been sweeping the state. They come across the grisly aftermath of one of those raids, with corpses and a burnt out wagon strewn like broken and discarded playthings on the scorched grass. Quite what three individuals are supposed to achieve where the full complement of a fort have failed is anybody’s guess. Their arrival is greeted with some suspicion by the local commander Colonel Meade (John McIntire), a feeling that will gradually be distilled into open hostility as he sees his approach sidelined and his authority not quite usurped but certainly undermined by Brady’s willingness to think outside the box. Meade is an adherent of the West Point manual, rigid in his views of both military tactics and the local tribes. Brady, on the other hand, is an opportunist at heart, a man who is prepared to take a more unorthodox path, and to improvise where necessary. His plan is to employ the kind of guerilla methods the Kiowa themselves have perfected, fighting fire with fire in a sense. And he’s keen to go a step further, to use the dispossessed and dislocated Seminoles as a sort of semi-official, roving commando. As the friction between the two schools of military thought grows in intensity there is another complication elbowing its way into Brady’s life. The widow (Maureen O’Hara) of one one of the fort’s officers who is missing presumed dead has caught his eye. In itself, that ought not to represent a great problem were it not for the fact that she appears uneasy, and perhaps unconvinced, over the fate of her husband, while the frankly radical daughter (Suzan Ball) of the Seminole chief is also showing signs of interest.

Sherman was a director who knew the genre and how to bring in a movie according to the studio’s requirements. Universal-International seemed to suit him and his time there saw him do some of his best work. I won’t claim that War Arrow represents him at his best, but it is an example of how he could produce a solid piece of entertainment from fairly ordinary material and get worthwhile work from his cast. His depiction of the Native Americans is as sympathetic as one would expect – granted the Kiowa do not come off well and act as bogeyman villains open to outside manipulation, but the Seminole fare much better. The script is by John Michael Hayes, someone who hadn’t much of a pedigree in westerns and who I tend to think of more in relation to his work for Hitchcock in the 50s, and it presents the Seminole in a strong light. They come across as indispensable to the success of the campaign planned out by Brady. They are seen as gutsy and committed, and a good deal more honorable than the frequently petty and hidebound Meade and his junior officers. Sherman gives plenty of time to this aspect, and shoots the battle scenes and skirmishes in a way that is both exciting and which highlights the contributions of the Seminole.

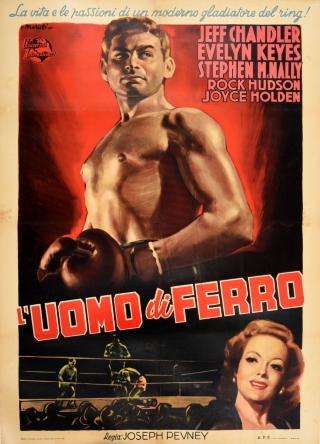

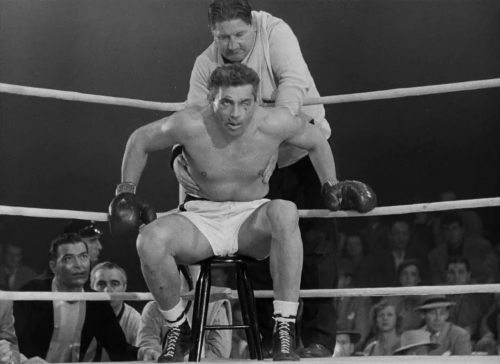

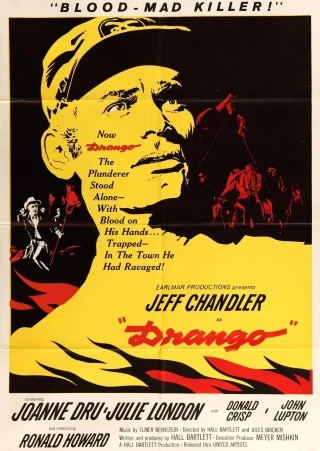

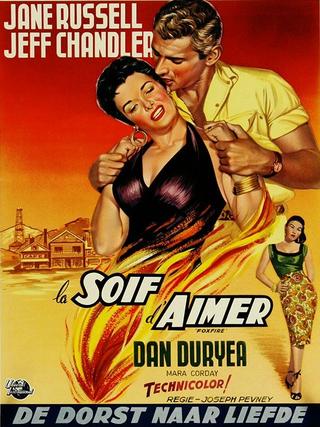

Jeff Chandler typically was good in military roles, either in westerns or contemporary war movies. Gravitas and authority came easily to him and these qualities could be tempered by thoughtfulness, inner conflict or iron determination as required. The part of Major Brady is a relatively straightforward one, an easy run out for him in essence and he carries it off with his usual smooth accomplishment. Maureen O’Hara made a number of films for George Sherman, including the director’s last Big Jake, with variable results. Personally, I think the actress did her best work in the genre for Ford, but this isn’t a bad effort and she is better in the latter stages where her character is given a little more depth. Suzan Ball was the other female star and she is marvelously forthright and assertive, although probably anachronistically so. It’s an attractively spirited performance and serves to emphasize the cruel tragedy of her short life – cancer would claim her just two years later at the age of 22. I think it’s fair to say that any movie benefits from the presence of John McInitre, a class act who could play it mean or sympathetic and who manages to inhabit the obduracy of his character here. Charles Drake and Noah Beery Jr add some lightness to proceedings, while Henry Brandon – still a few years away from his most memorable role as Scar in The Searchers – is the Seminole chief Maygro, with Dennis Weaver and Jay Silverheels filling the other native parts.

It always pleases me to sit down with a George Sherman film, especially one of his westerns. Even if War Arrow isn’t among his top titles, it still shows his professionalism and his sensibilities as a director are apparent, not least with regard to how he viewed Native Americans. The movie shouldn’t be that difficult to track down on DVD although the German Blu-ray, originally released by Koch Media, that I picked up years ago sadly seems to have drifted out of print.

I’m offering this as a contribution to the Legends of Western Cinema Week being hosted by Hamlette’s Soliloquy and others.