Over a decade ago (it really doesn’t seem that long… ) I posted a list of western actors. I followed that up with a post on western directors, film noir directors, and film noir stars. The latter included a mix of male and female stars and it has long been my intention to put up a list that would balance that first entry by turning the spotlight on the women who made significant contributions to the western. I’m not sure why I’ve left it so long, I guess other things just kept getting in the way and it got shunted off for another day. There are those who would say the western is an inherently masculine genre, but I don’t feel that’s a fair or just assessment. The western was and remains one of the greatest of all cinema genres precisely because it was so malleable, was so dependent on absorbing myriad influences, and drew highly creditable work from such a wide range of personnel. So, let’s cut to the chase and have a look at ten actresses who added immeasurably to my my enjoyment of my favorite genre.

Felicia Farr

I can’t imagine opening this list with anyone else. Felicia Farr’s part in 3:10 to Yuma is comparatively small yet it’s a pivotal one. Those short scenes she shares with Glenn Ford’s outlaw are memorable and powerfully touching, adding another layer of yearning and regret to an already poignant movie. Director Delmer Daves also used Farr in two other fine westerns, The Last Wagon and Jubal, while George Sherman cast her to good effect in Hell Bent for Leather and Reprisal.

Virginia Mayo

Making her western debut in Colorado Territory, Raoul Walsh’s remake of his own High Sierra, Mayo impressed herself on the genre right away. I won’t go into spoilers here for those who haven’t seen it but the climax of that film is as tragic as it is poetic, and Mayo’s actions give it its power. Walsh would cast her again in the underrated Along the Great Divide while she had other good parts in The Proud Ones, Great Day in the Morning and Fort Dobbs to name just a few.

Dorothy Malone

While Virginia Mayo was the passionate, beating heart of Colorado Territory, her rival for the affections of Joel McCrea’s doomed outlaw was a coquettish and calculating Dorothy Malone. She would take on some terrific roles throughout the 50s, including some very respectable films noir as well as a couple of plum parts for Douglas Sirk – the superlative The Tarnished Angels and an Oscar winning performance in Written on the Wind – and of course plenty of westerns. Among the highlights are At Gunpoint (why has this movie never had a decent release anywhere?), Pillars of the Sky, Quantez, The Last Sunset and Warlock.

Barbara Stanwyck

One of cinema’s great actresses, Stanwyck made couple of westerns in the 1930s and 1940s (Annie Oakley, Union Pacific and California) but it was in the 50s that she made her mark on the genre, and fell in love with it in the process. Starting off with the emotionally charged and wondrously melodramatic The Furies for Anthony Mann, she would regularly return to the west. Some of those films were only partially successful, but a movie like The Violent Men has much to recommend it and Samuel Fuller’s Forty Guns is an enduring classic in my opinion.

Vera Miles

Anyone who worked with John Ford, and was cast in major roles in his films has to be worthy of consideration here. Vera Miles had started out in the genre with a part in The Charge at Feather River and in Jacques Tourneur’s Wichita. These are fine movies by any standard yet a top role in The Searchers, which is arguably the best western of all time, and one of the best films of any kind, lifted her into a different league. The fact Ford cast her again in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, one of the key films marking the close of the classic western era cements her place for me.

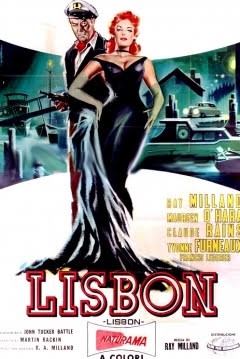

Maureen O’Hara

The Ford connection is strong with the next entry on the list, even if their western collaboration was limited. The fiery Irish redhead had already made Comanche Territory when Ford used her opposite John Wayne in Rio Grande, unfairly regarded by some as the least of the director’s Cavalry Trilogy. She would work memorably with Ford and Wayne again in other genres and went on to make good westerns such as War Arrow (George Sherman) and The Deadly Companions (Sam Peckinpah’s debut feature).

Claire Trevor

Sticking with Ford (and indeed Wayne) for the present, we now come to Claire Trevor. It’s hardly too much to say that Stagecoach was instrumental in boosting the status of the western, lifting it firmly and decisively into the A class where it would continue to hold a dominant position for the next quarter of a century. Trevor’s turn as Dallas, the “fallen woman” driven out of polite society only to find love, respect and a future with Wayne’s Ringo Kid, is a superb piece of work. Perhaps her subsequent westerns didn’t offer the same scope for her abilities – Texas, Dark Command (Raoul Walsh), The Desperadoes, The Stranger Wore a Gun – but she was a regular visitor to the cinematic west, and that ride on the Lordsburg stage counts for a lot.

Katy Jurado

The Mexican actress with maybe the most soulful pair of eyes in the business. The wistful look she bestows on Gary Cooper as he stands alone in an empty street in High Noon is as good a way to announce one’s arrival in the genre as I can think of. She brought her unique quality to such movies as Broken Lance, Man from Del Rio and The Badlanders throughout the 1950s. Her appearances in westerns tailed off after that, One-Eyed Jacks with Brando in the next decade and then a small but hugely affecting part in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

Julie Adams

Anyone familiar with my writing over the years will be aware of how much I enjoy the output of Universal-International, and the westerns that studio produced are among my favorites. Sometimes it feels as though it’s impossible to watch a U-I western and not see her. Budd Boetticher frequently used her in his movies for the studio – Wings of the Hawk, Horizons West, The Man from the Alamo – and she had good roles for Anthony Mann in Bend of the River and Raoul Walsh in The Lawless Breed and then later on in Joseph M Newman’s The Gunfight at Dodge City.

Debra Paget

Starting out with some small roles in notable films noir (House of Strangers, Cry of the City), Paget struck western gold in the influential Broken Arrow for Delmer Daves. In a sense, one could say she became typecast in westerns, finding herself playing yet again a Native American in White Feather (scripted by Daves) and the powerful and visceral The Last Hunt for Richard Brooks. Typecast or not, she brought a great deal of dignity to those parts and the western genre would be poorer without her performances.

So there it is, my list of ten actresses who have enriched the western over the years. I had to indulge in a bit of ruthless trimming to keep it down to ten, but that’s to be expected and I also anticipate that my picks aren’t going to satisfy everyone. Well, that’s the nature of lists and half the fun is hearing others point out who they would have included instead. Feel free to disagree in the comments section below.