Where possible, I like opening a post with a quote that either sums up the sentiments of a movie or at least captures something of its mood. There was a comment by Douglas Sirk on his own work that I felt would be apposite here yet, for the life of me, I can’t locate it just now. As such, I’ll have to settle for the gist of it: it ran along the lines that he liked to make movies about characters who were forever in pursuit not of some dream of the future but instead of their own past selves, straining to reconnect with or recapture something of their youth, something precious lost in the midst of the messy business of living. That notion is steeped in the kind of melancholic reverie that is very appealing. It encapsulates enough unattainability to lend an air of tragedy to any drama and at the same time there is too the promise that maybe some flavor of a spirit since departed can be held onto, some faltering beacon to serve as an anchor. The Tarnished Angels (1957) has a lot of that spirit coursing through it, describing a cyclical, circular path of beginnings and endings, and still offering a shot at renewal and rediscovery as it draws to a close.

The entire concept of the barnstorming pilots traversing the country every season and spending much of their time racing around the massive pylons that mark the course of their near suicidal races is in itself circular. Round and round they all go, chasing the prize money and the fleeting adulation of a crowd of vicarious thrill seekers who will forget the broken daredevils before the ambulance or hearse hauls away whatever remains of them when the shrieks and cheers have faded away. Yes, round they go with all the futility of dogs chasing their own tails, tarnished by their own cut price way of life and with no realistic chance of ever touching the person they once were. Yet, no matter what might pick away at one in the darker moments of life, human nature is sustained not by defeatism but by hope – it is one of the key or defining elements of the human condition after all. So it is with Roger Shumann (Robert Stack), his wife LaVerne (Dorothy Malone), son Jack (Chris Olsen) and their mechanic Jiggs (Jack Carson). These four live a nomadic, gypsy existence, knowing no home beyond their own dreams. Roger Shumann is a figure carved from classical tragedy, a hero in the eyes of others who is terrified by his own limitations. He is one of those post-war lost souls, a man cast adrift in a world that celebrated the feats of courage he once displayed and now bewildered by the artificiality of trying to recreate that daring. And there’s guilt too, that illogical but unshakeable questioning of many who lived through conflict of why one has survived while others paid the ultimate price. It’s a blind too for his own insecurities as he substitutes recklessness in the air for paucity of courage in his personal life. Of course, the route Shumann takes towards redemption in this respect forms one of the major pillars of the story – the brooding intensity of the man is well realized by Stack as he shies away from true affection and then plumbs the absolute depths of moral dissoluteness. His request that LaVerne should quite literally prostitute herself to secure the use of a plane is a shocking moment, the decay of a soul laid bare. From this nadir though he rises again, finally, to first acknowledge his love and then take to the skies to make a last attempt at touching what he once was, and earning for himself something of value through an act of unplanned heroism.

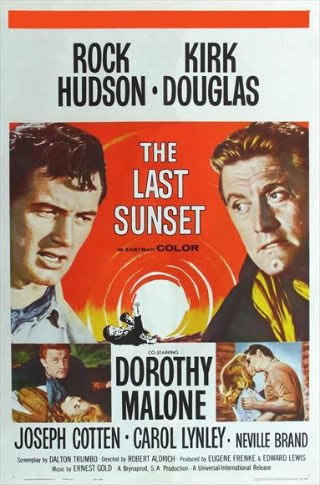

The setting fits in with the cyclical theme too, taking place over the course of Mardi Gras in New Orleans, that carnival celebration that peaks and fades every year and marks the end of indulgence and the last chance to feast and cut loose before the penance and deprivation of Lent begins. It signals the end of Roger Schumann’s time; he has been afforded a taste of his days as a better man and it also represents the opportunity for his wife and child to start afresh. Dorothy Malone did the best work of her career for Sirk – she had won an Oscar for Written on the Wind and The Tarnished Angels was a chance to work again with the same core team of Sirk, producer Albert Zugsmith, writer George Zuckerman, Stack and Rock Hudson. Her performance here is every bit as good and perhaps better than that award winning role, LaVerne Shumann being a marvelously true creation and wholly credible in her disappointment and disillusionment yet never lacking that spiritual vitality that sustains life. Sirk’s camera lingers with care and tenderness on her features time and again, as she reads My Antonia, sips her drink, smokes her cigarette, or just surrenders to lonely wordless reflection.

She is at her best in her interaction with Hudson’s alcoholic Burke Devlin, the journalist who ended up a hack reporter but who sees the Shumanns as his way back into the world. He starts out with his mind set on exploiting a bit of cheap sensationalism before coming to the realization that the story he thought he was covering is only a cloak for a more timeless tale, something that is worth telling in its own right and which may represent his salvation too. Hudson gets to deliver a superb monologue right at the climax, one that is in turns heavy with reprobation and hope. However, some of the finest moments are those quiet ones in his run down apartment with Malone where all the bumps and hollows of life are navigated in the half light.

Tragedy pays a visit to all those characters, but it doesn’t loiter around them. It wipes the slate in a sense before passing on and leaving the door at least ajar for something more positive to slip in. Jack Carson’s Jiggs is maybe the exception, his destination left undefined at the end. Carson was a great character actor, bulkily comedic in many a picture though generally with a strong sense of pathos about him. Jiggs is a loyal figure, but there is a strong suggestion that the loyalty is largely as a result of his unfulfilled love for LaVerne. He has a couple of standout moments in the movie; his appalled outrage at Shumann’s insensitivity first when he displays jaw-dropping cheapness in drawing spots on a pair of sugar cubes to simulate dice and then proceeds to use them to shoot for the responsibility for bringing up Laverne’s child, and then his reaction to Roger’s shameless exploitation of his wife. Finally, there is that moment at the end of Roger’s wake when everyone drifts away and the lights are slowly doused, when he stands alone in the shadows abandoned and bereft. The other supporting roles are filled with accomplishment, but less shading overall by Robert Middleton and the perpetually sneering Robert J Wilke. A quick word too for Chris Olsen. The child actor only had a brief screen career but a glance at some of his credits – The Tall T, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bigger Than Life – reveals a lineup to be proud of.

I think The Tarnished Angels is Douglas Sirk’s best film, though I suppose some others might opt for one of his other melodramas. William Faulkner certainly seems to have considered the movie the best adaptation of his writing, something I wouldn’t want to argue with. I’ve seen the film many times over the years and it affects me strongly on each viewing, generally revealing some new insight or idea as all the great pictures do. Sit back and watch it if you haven’t done so, or just watch it again if you have.